Latin America

Text and selection of content: Michael Aronna

Committed to social justice in Latin America

Since the nineteen-seventies, the connections between the political, social and cultural repression of the Franco dictatorship in Spain and the emergence of the struggle against authoritarian regimes in Latin America caught the journalistic, political and literary attention of Manuel Vázquez Montalbán as a writer, public intellectual and plurinational Spaniard committed to social justice and leftist policies in Latin America. This political and personal commitment was especially reflected in his position against the dictatorships in Chile and Argentina and was also manifested through decades of solidarity with, and defence of, the Cuban Revolution during different phases and political and economic challenges on the island with the fall of the Soviet bloc and the crisis of the so-called “special period”.

Selection of texts

Peronisme

Vázquez Montalbán, Manuel. «Posperonismo», Tele/eXpres, 1 de juliol de 1974.

Borges i Guerra Bruta

Vázquez Montalbán, Manuel. «Borges», El País, 26 d’abril del 1985.

Transició i Alfonsín

Vázquez Montalbán, Manuel. «Alfonsín», El País, 20 d’abril del 1987.

Quinteto de Buenos Aires i les seves influències culturals

«—The tango once again. You deny the tango, you want to get away from it but you will come back to it inexorably. The country itself is a tango. This city is a tango.» Vázquez Montalbán, Manuel. Quinteto de Buenos Aires. Barcelona: Plantea, 1997, p. 75.

«—There are many possible and at the same real Spains —Carvalho continues—, just as there are many possible and real Argentinas. Who can speak on behalf of those totalities that are so complex?» (Vázquez Montalbán, Manuel. Quinteto de Buenos Aires. Barcelona: Plantea, 1997, p. 467.)

Vázquez Montalbán, Manuel. “Dos Mujeres”. El País, 11 May, 1998.

Vázquez Montalbán, Manuel. “Adriana Varela: o tango o cocaína”. El País, 1 August, 1998.

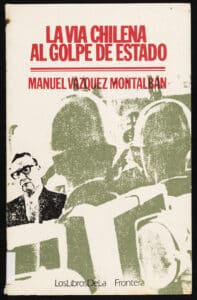

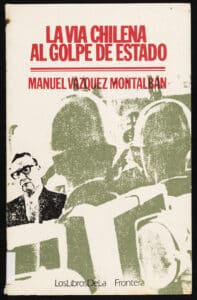

«The events in Chile caused a worldwide commotion, at least as much as one would expect in the era of information overload, in which the abundance of news stimuli produces a certain insensitivity as a response by the receiver. The world, in general, had a false impression of what had happened there. Allende’s heart-wrenching struggle for survival seemed like [that of] any European bourgeois, something like the parsimoniously electoralist and reformist Willy Brandt. The images from Chile arrived truncated by the mythology and by the conventional wisdom: Allende the pacifist, an army loyal to the constitution, advanced Christian Democracies…these fake images muted the shrillness of a long, deep, broad tragedy that would explode on 11 September.» (Vázquez Montalbán, Manuel. La vía chilena al golpe de estado. Barcelona: Los libros de la frontera, 1973. p. 177.)

Democratic transition and the 1988 plebiscite

Vázquez Montalbán, Manuel. «Cono Sur», El País, 17 de setembre del 1990.

Trip to Xile

Vázquez Montalbán, Manuel. «Manuel Vazquez Montalban, escritor español, de visita en Chile». Qué Pasa, núm. 818, 22 de marzo de 1993, p. 30. retr.

Vázquez Montalbán, Manuel. «El viaje», El País, 19 de març del 1990.

Vázquez Montalbán, Manuel. «La Santísima Trinidad del 11 de septiembre». La Jornada, 11 de septiembre de 2003

Transcription of Vázquez Montalbán, Manuel. «El marxismo tropical», Tele/eXpres, 4 de febrer del 1974.

Visit of Pope John Paul II

«So religion is useful for something, I think and remember Aurelio Alonso’s observation: the mood of the masses before the Pope’s visit is not fervent but expectant, they will see if something happens, see if this man manages to get more dollars from Miami. The religious mental structure of the people in Cuba, almost everyone agrees, is transactional, very closed to the prophetic, and perhaps that pragmatic religiosity also marks the attitudes towards the political, where in general something is expected to happen, but only after Castro. Whoever you talk to, Borau says, everything hinges on Castro’s shuffling off his mortal coil, far from the fears or hopes of the early nineties when foreign action was foreseeable. There is still a minority that awaits the emergence of a revolutionary energy that will redirect its objectives along the path of participation, of critical freedom, of pluralism, as James Petras proposes in his conversation with Eduardo Giordano about the left after the fall of the [Berlin] wall.»(Vázquez Montalbán, Manuel. Y Dios entró en la Habana. Madrid: Ediciones El País, S.A., 1998, p. 133)

Interview with MVM about Y Dios entró en la Habana

- Transcription of Martorell, Manuel. “Ni la historia ni la revolución se han terminado” , El Mundo, 15 December 1998.

- Transcription of Vázquez Montalbán, Manuel. “Creemos en la revolución”, El País, 18 January 1998.

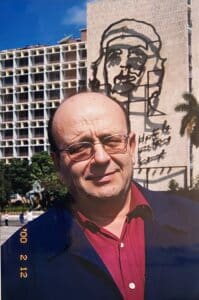

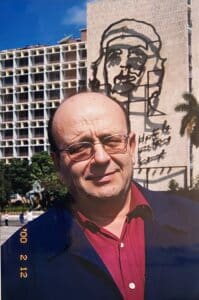

Vázquez Montalbán in Revolution Square in Havana. February 2000. Photograph of HadoLyra, released by the photographer.

Excerpt from Michelini, Alberto. Cuba, te amo. 2004. 5: 14 minutes. Pope John II’s papal visit to Havana.

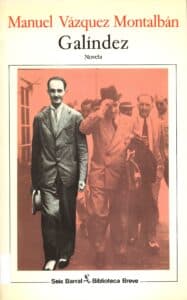

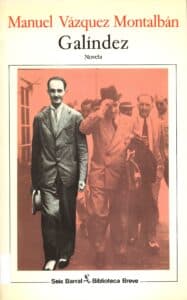

«Manuel Vázquez Montalbán chose a sonorous surname for this excellent novel: Galíndez. He chose a surname that can symbolise, materialise and summarise the turbulent times of Spain’s recent history, of the history of the Dominican Republic, and even United States’ foreign policy in the nineteen-fifties.

Galíndez, let’s say it right away, is a novel about what we now call ‘Evil’. I don’t know how to call it by any other name. I don’t know what other word to use for barbarity, for the total absence of truth, of justice. I call the barbarity of history in 2018 “Evil” with a capital E. And that’s what this book is about. It speaks of the abominations and moral corrosions, it speaks of the malignant political power, it speaks of the underdevelopment inherent to any form of political demonstration of Spain and its Latin American offspring.» (Silva, Manuel “Galíndez: una novela peligrosa”. Galíndez. Madrid: Anagrama, 2018, p. 7

Vázquez Montalbán, Manuel. “Vascos en Santo Domingo”, El País, 19 February 1990.

Vázquez Montalbán, Manuel. “El héroe impuro”, El País, 9 September 2002.

Galster, Ingrid: “Entrevista con Manuel Vázquez Montalbán. A propósito de su novela Galíndez (1990)”, Iberoamericana 3-4. 63/64 (1996): pp. 72-84.

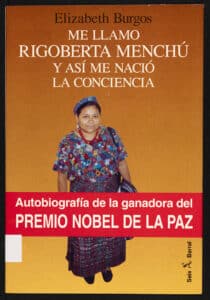

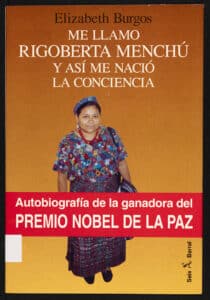

«My name is Rigoberta Menchu. I am twenty-three years old. I want to give this living testimony which I have not learned in any book and which I have not learned alone either, as I have learned all of this with my people and it is something I wish to draw attention to. It is hard for me to recall the whole life I have lived, since very often there are very dark times and there are happy times too, yes, but the important thing is, I believe, that I want to stress that I am not the only one, many people have lived through the same experiences as me, it is the life of all. The life of all poor Guatemalans. I will try to tell a small part of my story. My personal situation sums up the entire reality of a people.» (Menchu, Rigoberta. Me llamo RigobertaMenchu y así me nació la conciencia. Mexico: Siglo XXI, 1985, p. 21 1st paragraph.)

The controversy stirred up by David Stoll

Vázquez Montalbán, Manuel. “Rigoberta”, El País, 11 January 1999

Solidarity with RM and indigenous peoples’ movements

«Is there a fear that the indigenous opposition movement may spread universally? (RM) “If it were only us, the indigenous people, I believe that nobody would fear us; we are synonymous with the women’s struggle, of black people, Chinese, Japanese, Hispanics, we are synonymous with a necessary roadmap of the future, the intercultural roadmap. There is no other way». (Vázquez Montalbán, Manuel. Y Díos entró en la Habana. Madrid: Ediciones El País, S.A., 1998, p. 701)

A meeting between Vázquez Montalbán, Rigoberta Mencghú and Frei Betto in Rome, on the cusp of the new millennium. Photograph of Hado Lyra, released by the photographer. Source: Colmeiro, Jose. El ruido y la furia: Conversaciones con Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, desde el planeta de los simios. Frankfurt am Main: Iberoamericana Vuevert, 2013, 105.

Peronisme

Vázquez Montalbán, Manuel. «Posperonismo», Tele/eXpres, 1 de juliol de 1974.

Borges i Guerra Bruta

Vázquez Montalbán, Manuel. «Borges», El País, 26 d’abril del 1985.

Transició i Alfonsín

Vázquez Montalbán, Manuel. «Alfonsín», El País, 20 d’abril del 1987.

Quinteto de Buenos Aires i les seves influències culturals

«—The tango once again. You deny the tango, you want to get away from it but you will come back to it inexorably. The country itself is a tango. This city is a tango.» Vázquez Montalbán, Manuel. Quinteto de Buenos Aires. Barcelona: Plantea, 1997, p. 75.

«—There are many possible and at the same real Spains —Carvalho continues—, just as there are many possible and real Argentinas. Who can speak on behalf of those totalities that are so complex?» (Vázquez Montalbán, Manuel. Quinteto de Buenos Aires. Barcelona: Plantea, 1997, p. 467.)

Vázquez Montalbán, Manuel. “Dos Mujeres”. El País, 11 May, 1998.

Vázquez Montalbán, Manuel. “Adriana Varela: o tango o cocaína”. El País, 1 August, 1998.

«The events in Chile caused a worldwide commotion, at least as much as one would expect in the era of information overload, in which the abundance of news stimuli produces a certain insensitivity as a response by the receiver. The world, in general, had a false impression of what had happened there. Allende’s heart-wrenching struggle for survival seemed like [that of] any European bourgeois, something like the parsimoniously electoralist and reformist Willy Brandt. The images from Chile arrived truncated by the mythology and by the conventional wisdom: Allende the pacifist, an army loyal to the constitution, advanced Christian Democracies…these fake images muted the shrillness of a long, deep, broad tragedy that would explode on 11 September.» (Vázquez Montalbán, Manuel. La vía chilena al golpe de estado. Barcelona: Los libros de la frontera, 1973. p. 177.)

Democratic transition and the 1988 plebiscite

Vázquez Montalbán, Manuel. «Cono Sur», El País, 17 de setembre del 1990.

Trip to Xile

Vázquez Montalbán, Manuel. «Manuel Vazquez Montalban, escritor español, de visita en Chile». Qué Pasa, núm. 818, 22 de marzo de 1993, p. 30. retr.

Vázquez Montalbán, Manuel. «El viaje», El País, 19 de març del 1990.

Vázquez Montalbán, Manuel. «La Santísima Trinidad del 11 de septiembre». La Jornada, 11 de septiembre de 2003

Transcription of Vázquez Montalbán, Manuel. «El marxismo tropical», Tele/eXpres, 4 de febrer del 1974.

Visit of Pope John Paul II

«So religion is useful for something, I think and remember Aurelio Alonso’s observation: the mood of the masses before the Pope’s visit is not fervent but expectant, they will see if something happens, see if this man manages to get more dollars from Miami. The religious mental structure of the people in Cuba, almost everyone agrees, is transactional, very closed to the prophetic, and perhaps that pragmatic religiosity also marks the attitudes towards the political, where in general something is expected to happen, but only after Castro. Whoever you talk to, Borau says, everything hinges on Castro’s shuffling off his mortal coil, far from the fears or hopes of the early nineties when foreign action was foreseeable. There is still a minority that awaits the emergence of a revolutionary energy that will redirect its objectives along the path of participation, of critical freedom, of pluralism, as James Petras proposes in his conversation with Eduardo Giordano about the left after the fall of the [Berlin] wall.»(Vázquez Montalbán, Manuel. Y Dios entró en la Habana. Madrid: Ediciones El País, S.A., 1998, p. 133)

Interview with MVM about Y Dios entró en la Habana

- Transcription of Martorell, Manuel. “Ni la historia ni la revolución se han terminado” , El Mundo, 15 December 1998.

- Transcription of Vázquez Montalbán, Manuel. “Creemos en la revolución”, El País, 18 January 1998.

Vázquez Montalbán in Revolution Square in Havana. February 2000. Photograph of HadoLyra, released by the photographer.

Excerpt from Michelini, Alberto. Cuba, te amo. 2004. 5: 14 minutes. Pope John II’s papal visit to Havana.

«Manuel Vázquez Montalbán chose a sonorous surname for this excellent novel: Galíndez. He chose a surname that can symbolise, materialise and summarise the turbulent times of Spain’s recent history, of the history of the Dominican Republic, and even United States’ foreign policy in the nineteen-fifties.

Galíndez, let’s say it right away, is a novel about what we now call ‘Evil’. I don’t know how to call it by any other name. I don’t know what other word to use for barbarity, for the total absence of truth, of justice. I call the barbarity of history in 2018 “Evil” with a capital E. And that’s what this book is about. It speaks of the abominations and moral corrosions, it speaks of the malignant political power, it speaks of the underdevelopment inherent to any form of political demonstration of Spain and its Latin American offspring.» (Silva, Manuel “Galíndez: una novela peligrosa”. Galíndez. Madrid: Anagrama, 2018, p. 7

Vázquez Montalbán, Manuel. “Vascos en Santo Domingo”, El País, 19 February 1990.

Vázquez Montalbán, Manuel. “El héroe impuro”, El País, 9 September 2002.

Galster, Ingrid: “Entrevista con Manuel Vázquez Montalbán. A propósito de su novela Galíndez (1990)”, Iberoamericana 3-4. 63/64 (1996): pp. 72-84.

«My name is Rigoberta Menchu. I am twenty-three years old. I want to give this living testimony which I have not learned in any book and which I have not learned alone either, as I have learned all of this with my people and it is something I wish to draw attention to. It is hard for me to recall the whole life I have lived, since very often there are very dark times and there are happy times too, yes, but the important thing is, I believe, that I want to stress that I am not the only one, many people have lived through the same experiences as me, it is the life of all. The life of all poor Guatemalans. I will try to tell a small part of my story. My personal situation sums up the entire reality of a people.» (Menchu, Rigoberta. Me llamo RigobertaMenchu y así me nació la conciencia. Mexico: Siglo XXI, 1985, p. 21 1st paragraph.)

The controversy stirred up by David Stoll

Vázquez Montalbán, Manuel. “Rigoberta”, El País, 11 January 1999

Solidarity with RM and indigenous peoples’ movements

«Is there a fear that the indigenous opposition movement may spread universally? (RM) “If it were only us, the indigenous people, I believe that nobody would fear us; we are synonymous with the women’s struggle, of black people, Chinese, Japanese, Hispanics, we are synonymous with a necessary roadmap of the future, the intercultural roadmap. There is no other way». (Vázquez Montalbán, Manuel. Y Díos entró en la Habana. Madrid: Ediciones El País, S.A., 1998, p. 701)

A meeting between Vázquez Montalbán, Rigoberta Mencghú and Frei Betto in Rome, on the cusp of the new millennium. Photograph of Hado Lyra, released by the photographer. Source: Colmeiro, Jose. El ruido y la furia: Conversaciones con Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, desde el planeta de los simios. Frankfurt am Main: Iberoamericana Vuevert, 2013, 105.

Contributions

Argentina

Vázquez Montalbán, Manuel. «Dos Mujeres». El País, 11 de maig del 1998.

Borges i Guerra Bruta. Vázquez Montalbán, Manuel. «Borges», El País, 26 d’abril del 1985.

On the influence in Argentina of the tango and Quinteto de Buenos Aires. Interview in the Argentinian programme Los siete locos 2005. 2:02-6:08 minutes

Castrillo, Marina. «Acordes Transatlánticos: Manuel Vázquez Montalbán y el tango como educación sentimental política». MVM: Cuadernos de Estudios Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, 2020, 5, 1, p. 67-97

Xile

Plebiscito de 1988: La cronología del 5 de octubre. 24 Horas. TVN Chile 5:57 minutes.

11 de septiembre de 1973: Bombardeo de La Moneda. 24 Horas. TNV Xile, 5-57 minutes.

Aniversario del 11-S: 21 años de los atentados contra las Torres Gemelas. El País. 5:14 minutes

Selection of articles about Chile written by Manuel Vázquez Montalbán. At: Solidaridad Internacional con Chile durante la dictadura cívico-militar.

Martín-Cabrera, Luis. Justicia radical: una interpretación psicoanalítica de las posdictaduras en España y el Cono Sur. Trad. Pablo Abufom Silva. Barcelona: Anthropos, 2016.

Cuba

Transcription of Martorell, Manuel. “Ni la historia ni la revolución se han terminado” , El Mundo, 15 December 1998.

Transcription of Vázquez Montalbán, Manuel. “Creemos en la revolución”, El País, 18 January 1998.

Excerpt from Michelini, Alberto. Cuba, te amo. 2004. 5: 14 minutes. Pope John II’s papal visit to Havana.

Buschmann, Albrecht. «El espejo empañado: Y Dios entró en la Habana. Entre reportaje literario y remodelación autoficcional». MVM: Cuadernos de Estudios Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, 2020, 5, 1, p. 46-66.

Ette, Ottmar. Esperando a Godot. «Las citas de Manuel Vázquez Montalbán en La Habana». Encuentro, num 14, autumm of 1999, p. 69-89.

República Dominicana

«El Generalísimo Trujillo en España». Rtve.es. 1952. Until minute 2:56.

Herrero, Gerardo. El misterio Galíndez. 2003. Nostalgia trailers. Trailer: 1:17 minutes

Diez, Ana. Galíndez. 2002. Documania. TV. 2:28-2:41; 39:07-39-50; 48:57-49:06; 101:09-101:32; 1:13; 16-1:13:35.

Bodenmüller, Thomas. «Galíndez o las posibilidades de la novela histórica moderna», Hispanorama 90 (2000), p. 75-79.

Colmeiro, José. «La re-escritura de la historia o la verdad sobre el caso Galíndez», Actas del XI Congreso de la Asociación Internacional de Hispanistas. Irvine: University of California, Irvine, 1994. Vol. 4, p. 211-222.

Gabilondo, Joseba. «Olvidar a Galíndez: Violencia, otredad y memoria histórica en la globalización hispano-atlántica», Manuel Vázquez Montalbán: El compromiso con la memoria. Ed. José F. Colmeiro. Woodbridge: Tamesis, 2007, p. 159-183.

Martín-Cabrera, Luis. «El No-Lugar: una lectura transatlántica de la memoria en Galíndez de Manuel Vázquez Montalbán», Revista de estudios hispánicos 40 3 (2006), p. 537-61.

Guatemala

Caricature by El Zurdo of Vázquez Montalbán as an indigenous person. El Diario [Nestor Cenizo]

Rigoberta Menchú, awarded the 1992 Nobel Peace Prize. Fundación Rigoberta Menchú Tum. First 3 minutes.

Beverley, John. “El testimonio en la encrucijada”. Revista Iberoamericana, Vol. LIX, No. 164-165, July-December, 1993.

Gacinska, Weselina. “Los movimientos indígenas y la globalización en los reportajes de Manuel Vázquez Montalbán”, MVM: Cuadernos de Estudios Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, 2020, 5, 1, pp. 26-45.

Salgado, Francesc. “La reflexión sobre Latinoamérica de Manuel Vázquez Montalbán en la prensa (1989-2003). Pensamiento único, disidencias, y globalización”. MVM: Cuadernos de Estudios Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, 2020, 5, 1, pp. 6-25.