MEXICO

Text and selection of content: Sergio García

The relationship with México

Selection of texts

«Look what’s happening in Chiapas. […] The killing of indigenous people by para-government butchers has justified the advance of the Army and an operation to harass the Zapatistas, that annoying revolutionary noise that got in the way of the “end of history” message perpetrated by former President Salinas and the United States. Look what’s happening in Chiapas because the ethical meaning of this end of the millennium is being played out there, as a symbolic referent, as an imaginary, if you will, of hope as a secular virtue.» (Spanish transcription of: Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, «Chiapas», El País, 12 de gener del 1998)

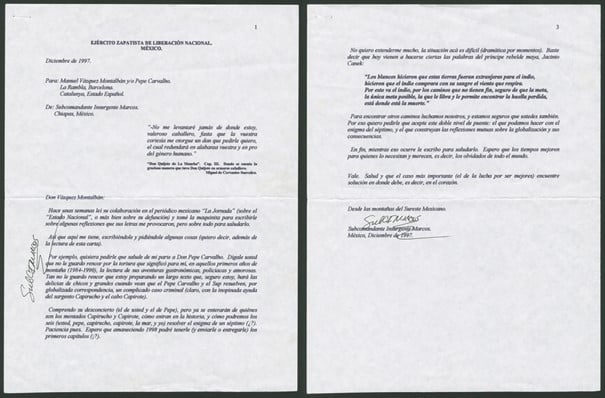

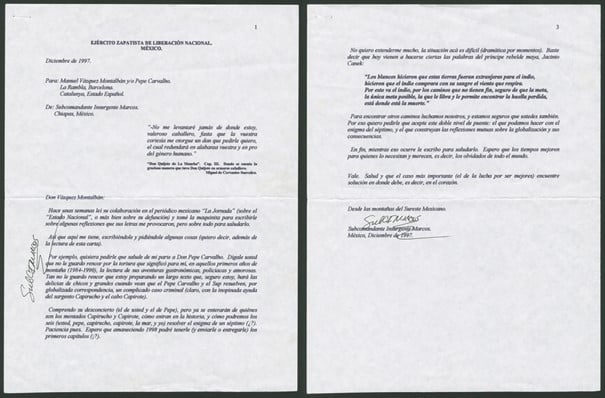

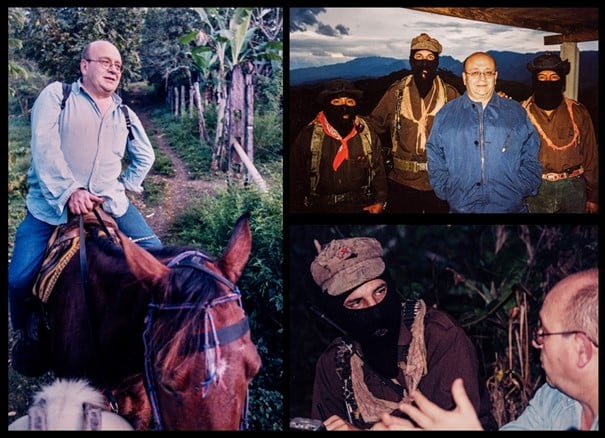

Letter from the insurgent sub-commander Marcos to Vázquez Montalbán, December 1997. Font: Biblioteca de Catalunya.

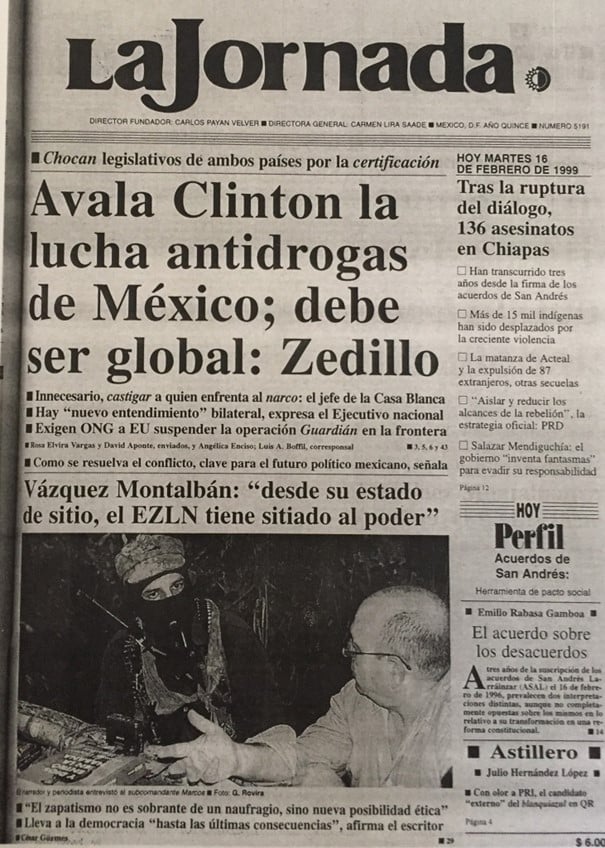

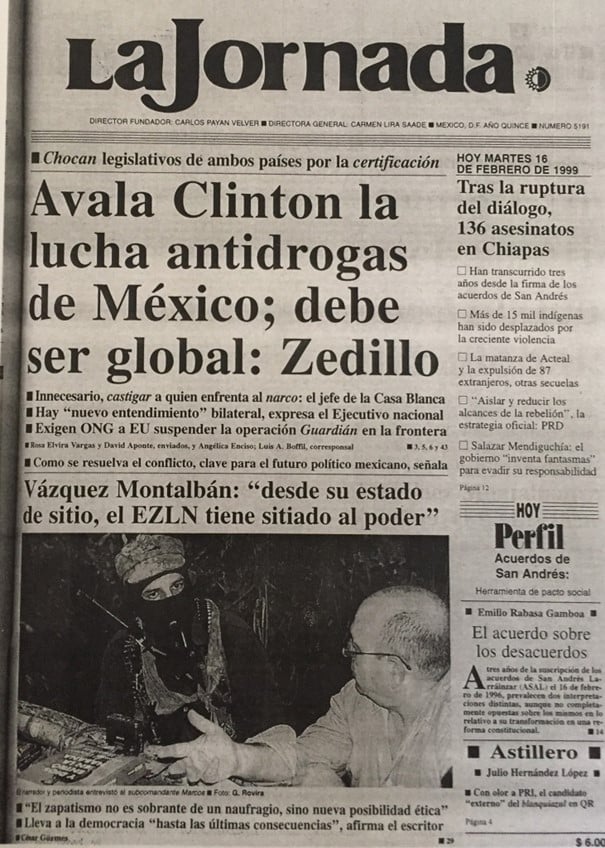

Interview of Vázquez Montalbán to Marcos. La Jornada, 16 February 2006.

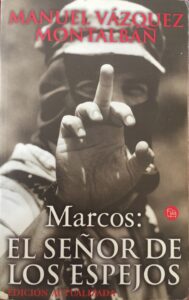

«What impression does Marcos make on me? He seems to me to be a classmate almost twenty years younger than me and twenty years younger than the residual left from which I am trying to extricate myself as if it were a viscous swamp.» (Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, Marcos: El señor de los espejos, 1999).

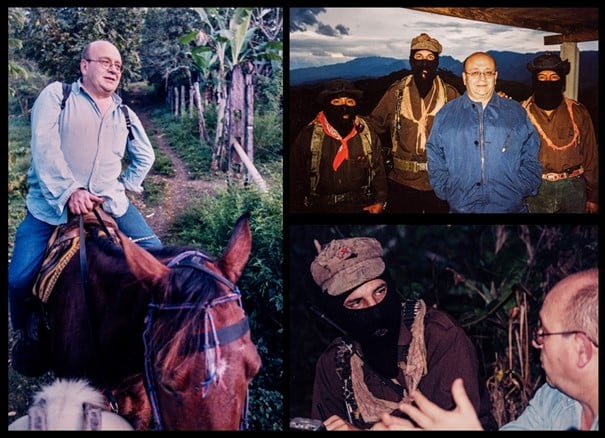

«In March 2001, Vázquez Montalbán returned to Mexico as one of the many foreign intellectuals who welcomed the arrival in the country’s capital of the March of Indigenous Dignity, carried out by the EZLN. In addition to other events, the writer participated in the Intercultural Meeting, held on 12 March, at the Olympic Village in Mexico City, where he pronounced the following words at the end of his speech: “The Zapatista movement also showed what mirrors are for and what masks are for. The mirrors, to abandon the tricked mirrors, which power had placed to deceive or self-deceive, and reveal the naked reality of social situations as they really were. The masks curiously were in order to be seen. Until this movement put masks on the indigenous people they were not seen, they were the invisible exploited. When they put on masks, they were seen and, moreover, it helped to reveal that power itself, economic, political and cultural power, wore its own masks. Faced with all these issues, valuing that we are in the presence of a movement that has given rise to the culture of resistance of the 21st century, I already have an answer to the question asked by the aid workers, to the boys and girls who have come to see up close what Zapatismo means. I have the answer: we foreigners have come to Mexico to learn.» (in Ramón Lopes, El espejo y la máscara. Textos anexos al documental México Ida y Vuelta, Madrid, Ediciones Caracol, 2004, p. 136).

«The March of Indigenous Dignity, which departed from San Cristóbal de las Casas in February 2001, was also attended by Daniel Vázquez Sallés, son of Vázquez Montalbán, as a journalist. In his book Recuerdos sin retorno (2013), he recounted some of those moments shared with his father: “I remember the morning of our meeting in a station in Mexico City. I will never erase that smile of yours, followed by a laconic but sufficient phrase: “I see you are well.” I had travelled three thousand kilometres as an unranked member of the “zapatour,” the mobilisation led by twenty-three commanders of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) and the “subcomandante” Marcos. And despite the effort not without dangers, in which I include the threats of the paramilitaries, various bites and a very painful revenge of Montezuma, I did not get to surrender to the arms of the Sub, possibly because of the inability to generate in my body the endorphins of idealism. If I ever believed in anything, I no longer remember, and I never managed to see Marcos as an ideological beacon. […] When on Sunday we finished the caravan in the town of Zocalo turned into chaos with nonsensical touches, I went to the hotel where you were staying. When I arrived, you were eating with Saramago, Pilar, Serrat, Candela, Sabina. You invited me to sit at the table, but I was exhausted and fell asleep. At night and on account of our inability to fall asleep, you because of jet lag, me because of the comfort of the bed, we began to talk about the trip and I remember that I told you with sadness about my experience during the caravan with the Italian communists who had joined the Tutti Bianchi movement. […] The weight that, little by little, modern civil society is gaining germinated again after many years lost in limbo during those four weeks in which we toured Mexico following in the footsteps of SubcomandanteMarcos. Whether we were revolutionary tourists, or revolutionaries, or tourists, or travellers, or assholes, or naïve, or superficial players of a children’s role-play well, that is of relative importance.»

«Don Vázquez Montalbán was not our friend, he was our companion. “Fellow traveller,” he said in one of his writings. “Companion, that’s all.” we said then and we say now. I don’t know if that’s more or less for him or for you. For us it’s everything. I think Vázquez Montalbán had a deep respect for the reader. I think he questioned what to write, why and against what, and that he passed on those questions to reading: what is read, why and against what. And I think that, as a writer, he didn’t expropriate the answers from his readers. Contradicting the title of one of his books, he made no pamphlets. On the contrary, he made the word a window, and again and again, in his writings, he took pains to keep it clean and transparent. Apart from neoliberals, the Word usually attracts respect among those who confront them, that is, those who speak and write them, and those who read and listen to them. If someone were to ask me for an example that synthesized humanity’s resistance to neoliberal war, I would say the Word. And I would add that one of its most stubborn, and fortunate, trenches is the book. Although, of course, it is a very different trench because it looks extraordinarily like a bridge. Because whoever writes a book and whoever reads it only crosses a bridge. And crossing bridges is a trope of any anthropology manual that is respected, it is one of the characteristics of the human being. I say goodbye, but I would not like to do so without first declaring that, if someone asked me for a definition of Manuel Vázquez Montalbán I would say that he was, and is, a bridge.» (Fragment from Marcos’s letter sent to the tribute to Vázquez Montalbán that took place on 28 November 2004 at the Guadalajara International Book Fair.).

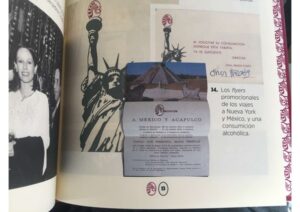

Promotional brochure of the trip to Mexico narrated by Jorge Herralde, which corresponds to the first trip that Vázquez Montalbán did to the Latin American country. Source: Toni Vall, Bocaccio. Donde ocurría todo, Destino, Barcelona, 2020, p. 13.

«Mexico is one of the most beautiful countries in the world, one of those countries that leaves you nostalgic and wanting to go back. I’ve told Encarna: when we lose the next civil war (which on this occasion would last three hours) I will go into exile in Rome or Mexico. […] For the craftsmanship, and not for the craftsmanship itself, but for craftsmanship as a symptom of the visual richness of a people. I would also go for the geography. The descent from Mexico to Cuernavaca with Popocatepel [sic] in the background is inimitable. Tasco[sic] growing on the mountains. All of the Yucatan, Cozumel, Can Cun [sic], Isla Mujeres. And I would go for the lobsters that you can eat in Puerto Vallarta at prices of sardines from Santurce. […] I would go to Mexico City to be able to walk through the colonial neighbourhoods of the Federal District: El Ángel, Coyoacán. To get hammered with margaritas in bars and anthropology in the museum of the capital. To be able to listen to Chavela Vargas live. For many things that do not belong so much to a possible tourist guide, they belong to the domain of intuition. I sense that Mexico could be my second country and that’s all there is to it. Too bad they sent Coronel de Palma as ambassador. I feel like I have been usurped. I want to be ambassador to Mexico. […] Encarna leaves me in the midst of a process of mental escape and when she re-enters my apartment I am in the Plaza Garibaldi in Mexico City fully immersed in destruction, music and the whiff of tacos.» (Sixto Cámara [Manuel Vázquez Montalbán], “Como México no hay dos”, Triunfo, 7 May 1977).

«The whales have not yet arrived or they are already leaving. It makes no difference. For a while they took refuge in the Sea of Cortez and now they look for their bread and plankton in other seas. In Cabo San Lucas the Pacific has opened up an ogival arch in the white rock. Not for nothing, the Californians call it the window of two seas. In Cabo San Lucas there are pelicans and sea lions. Precooked or pre-frozen gringo tourists, I no longer remember, and two single ladies who are from Puebla, but they could equally be from Cuenca, who wear a Nikon as if they were carrying a fan, and laugh, they always laugh so that the gringos forgive them for being from Puebla, being from Cuenca, being single, the fan. Or perhaps the Nikon. The ladies from Puebla, I mean from Cuenca, spot a warship and fan it for me, naturally with the Nikon. An American warship, that is, American in its flag and in its bow gun; American tout court in everything else, especially in its stern wind, and while the young ladies from Puebla, I mean from Cuenca, fan the sentry with their laughing photos of spinsters on vacation, the pre-frozen or precooked gringos stand firm so that their photographs are a visual hymn to the patrolling. Baja California is closer to the US dollar than to Mexico City, and it seems to one that the North American ship is like a dot on the i of this Finisterre. The whales will return, according to a secret pre-Columbian logic; sea lions smell of stale fish and are on the payroll for tourists, as are pelicans and pre-Columbian boatmen, all indifferent to the colour of flags and cannons. The Creoles of Puebla laugh and laugh among gringo couples who smile (Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, “Las señoritas del abanico”, El País, 27 March 1984. This text was the starting point of a eponymous story, included in Pigmalión y otrosrelatos [1987], and of the poems ‘Finisterre de California…’ and ‘La modernidad adosó un squash…’).»

«Finisterre of California / the whales have left / window of two seas / Cabo San Lucas / sad pre-frozen gringos / sea lions and pelicans / two young ladies from Puebla / or were they from Cuenca? / flutter with the fan / or was it a Nikon? / were photographing photographed a US warship / the bow gun / American the stern wind / photographed / caressed the bow cannon with the fan.» (Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, “Finisterre de California…”, poem included in Pero el viajero que huye [1990]).

«Modernity attached a squash / to the old pantheon of Trotsky / his slaughterhouse / is now a museum corner Vienna / Morelos / Coyoacán Mexico Federal District / with their backs to History / squash players fight / against age and excesses / of fat in the blood and eyes /others/[…] near / the ashes of Trotsky and Natalia Sedova / among myrtles and carnal flowers/ of a garden of insufficient aroma / they join in the dual failure of love / and history.»(Excerpts from “La modernidad adosó un squash…”, poem included in Pero el viajero que huye).

«I confess my nostalgia for Mexico when the occasion arises, and now that I can be here, even I am just passing through, I rethink my Mexican imaginary built on the basis of romantic revolutions, fundamental writers, Chavela Vargas, Lázaro Cárdenas, ten or twelve in a row indispensable for survival, all the taibos all, all the mixtures and landscapes and people of a country that is a forerunner of the future universal mixing of races.» (Transcription of Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, “México”, El País, 15 February 1999)

«Jorge Negrete was very deep inside the chest of the men and women of Spain. His machismo was ours, his whiskers ours, his virile melancholy ours, his reckless spirit ours. Few singers have been so sung, few have put in Hispanic throats more and better voice cracks. […] In the radio contests that looked for new stars, there appeared the little boy with the big lungs who with his hands wide open and his chin almost sunk in his Adam’s apple, started off with: Oh, Jalisco, don’t give up. / It comes from my soul to shout with heat. / Open your whole chest to shout out loud/How beautiful is Jalisco, upon my word! It came from the soul, from the cojones of the soul, as Miguel Hernández had been able to express the place where the Hispanic brain took refuge in a primitive pilgrimage of Cro-Magnon man. […] But it was nothing comparable to that cry of Mexican affirmation that vibrated with machismo in all the tumblers of the glassware of Spanish homes. I am Mexican, my land is brave […]. Negrete would have been nothing without his Hispanic gigolo moustache, without his somewhat cynical look and without that voice that came from the highlands of his chest. He was a very usable singer, because he came from one of the lands of the world where the most Spanish refugees had been taken in, where more and better Spanish refugees had laid down their mattresses and cast their nets, in search of the dream of the fugitive and fishing for the hungry. That is why here he was honoured as if he were a great recovered Creole chief (Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, Crónica sentimental de España, 1970).

«One of the main political problems of the new Spanish regime [Franco’s regime] was re-establishing diplomatic ties with Latin American nations. Many of the Spanish political exiles sought refuge in the Spanish-speaking republics and especially in Mexico, where they were excellently welcomed by President Lázaro Cárdenas. It is not surprising, then, that the official propaganda turned to the works of the Mexican composer Agustín Lara. The composer personally broke the political blockade and flooded the Spanish market with excellent songs, often directly inspired by motifs from Spain: “Madrid” was the most popular song for many years and glorified the new version of the capital of Spain built on the ruins of the republican resistance.» (Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, Cien años de canción y Music Hall, 1974).

«[Chavela Vargas] is perhaps the best popular Spanish-speaking singer, and she has achieved it as these things are achieved: based on a lot of alcohol, memory and desire. […] Chavelabelongs to the communion of blues singers, an irritating pressure group that gets you down from time to time, especially when the night complicates loneliness. So far, Chavela is little known in Spain. I heard “Macorina” for the first time in 1965. […] What a song! It’s the most beautiful erotic message of all popular poetry. […] I will only say that from time to time I play it, when I run out of real or mental loves and need that essential dose of self-pity to continue being a statue of salt before the forbidden cities.» (Sixto Cámara [Manuel Vázquez Montalbán], “Chavela Vargas“, Triunfo, 14 July 1973).

«When I find you / in the storage room of the world / Chavela / I will be indiscreet / I would like / to know what happened to your Macorina / if you knew what to do / of that smell of woman / mango and new [sugar] cane / I forgive you / for the women you have taken from me / in exchange for you singing to me / forbidden bodies / hot as danzónes / cinnamon colour moistened by desires /[…] the old Macorina no doubt ill-loved / in the years when it was not yours / or mine / but a progressively absurd body / abandoned by guitars and laments.» (Excerpts from “Ponme la mano aquí“, poem included in A la sombra de las muchachas sin flor [1973]).

«From the ancient rituals, the food and the rite of the day of the dead are preserved, a cultural variant of the ancestral custom of providing food to the deceased so that they arrive well-nourished on the other shore. But in Mexico the Catholic-pagan melting pot has given rise to a picturesque gastronomic and funerary festival that today is a must-see for both the anthropologist and tourist. No matter how humble the house is, and mainly in the states of Puebla, Mexico, Oaxaca and Michoacán, on 31 October and 1 and 2 November, offerings are made to the dead: sweets, fruits and dishes as succulent as they are different. Christianity contributes to the festival with its sacred imagery arranged on an altar, and paganism contributes with a well-laid table with black glazed clay crockery, full of these stews: molewith guajalote, pork or chicken, pumpkin dessert, tejocote, guava, all sprinkled with toasted sesame seed, as well as covered with a sweet bed of blue, purple or red corn. The pagan picture is completed with fruit and sugar skulls with the eye sockets covered with brightly coloured papers, adorned with sugar filigree and the names of dead loved ones written on the forehead. The playful-funerary inventory is impressive: skull-shaped breads and skeleton leg bones, egg bread called hojaldres or “pan de muerto“.» (Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, Contra los gourmets, 1985).

«The Mexicans have a special talent for cocktails. Anyone who hasn’t tried margaritas or daiquiris made by Mexican bartenders doesn’t know what’s good. […] Although it may seem like a contradiction for the palate and a desperate challenge in the heat, I recommend that after warming up the fundamental muscles with piña colada, the visitor to the Yucatan surrenders not to the excellences of the local cuisine, one of the most elaborate in the world, but to the brutality of a mestizo stew, son of a conquering father and Yucatecan mother.»(Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, ‘Piña colada’, Interviú, 10 January 1980).

«First of all, corn, for the taste and variety of use. Then, when I made a road trip of Mexico, my first great impressions were made by the mole poblano in the place where they prepare it. That combination must have been inspired by some god to a nun. A fun-loving god, not a Christian one. Mole is an imagined dish in a state of grace.» (Interview by César Güemeswith Vázquez Montalbán, La Jornada, 18 February 1999).

«While waiting for Parra, Carvalho thought of other poets of odd trades. Emilio Prados working as a monitor for children at break time in a school in his Mexican exile. Or that poet who ended up as a kindergarten teacher in Tijuana. Carvalho met him at a bar on the border drinking tequila with salt after tequila with salt and, between glasses, half a sip of water with baking soda.

—Until Franco dies I’m not going back. It’s a moral fact. Even though I’m a nobody. But I have my pride. I appear in the youngest anthologies before the [Spanish Civil] War. Justo Elorzía. You’ve never read anything of mine? I’ve barely been able to move to publish again. From Argeles concentration camp to Bordeaux, then the ship, Mexico. And as soon as I arrived, I fell on my feet in Tijuana. A temporary job at a school. Temporary. Thirty years, my friend. Thirty years. Every time I hear a rumour that Franco was sick or about to fall, I stop shaving, pack my bags and don’t change the sheets on my bed. So that everything would push me to leave here. A few months ago I despaired. I have twenty books of unpublished poems, friend. I went down to Mexico to talk to Exprésate, the Era editions. I know Renau a lot, the poster painter. Now he’s in East Germany. Well, the girl from Era is the sister of a son-in-law of Renau. They proposed me to make an anthology. Do you hear? An anthology of books that have never been published. It’s like killing them one by one .» (Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, La soledad del mánager, 1977).

«From the shelves still full of books he extracted Las buenas conciencias by Carlos Fuentes, a Mexican writer whom he had met by chance in New York during his time as a CIA agent and seemed to him an intellectual who lived at a sideways angle, at least he greeted you sideways on. He had shaken his hand as he looked westward. Such cavalier treatment had been received by Carvalho without Charro knowing that he was in the CIA, knowledge that at least would have justified his attitude for ideological reasons. But Carlos Fuentes had no reason to barely shake his hand and continue to look west. They were in the house of a Jewish Hispanist writer named Barbara, whom he was watching by order of the State Department, because it was suspected that in her house a clandestine landing in Spain was being prepared to kidnap Franco and replace him with Juan Goytisolo. The Spanish embassy cultural attaché was telling him surreptitiously about the background of the staff that were moving through that party. […] Of special interest was a Spanish writer who tried to convince anyone who wanted to hear him that the best dish of Spanish cuisine next to any dish of Arab cuisine was a fabada[…]. Carvalho wrote a report for the CIA in which he tried to show that they were harmless people who lacked affection, like almost everyone. Or it had not been exactly like that, but the truth is that Carlos Fuentes had treated him contemptuously without any justification and his novel was going to serve as basic combustible material for the campfire that was going to warm his house and soul.» (Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, La Rosa de Alejandría, 1984).

«—Don’t exaggerate, boss. If the plane crashes, much more would be lost than the photographs. Have you been to Mexico?”

—Yes.

—Is it such a sick country as they say?

—It’s a beautiful country.»

(Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, “La guerra civil no ha terminado”, Historias de política ficción, 1987).

«The next day some cases were opened and remained for a long time before the Western Wall, recording the variety of costumes of the Jews who were going to lament by means of a ritual resemblance of moaning, although there were those who almost crashed their foreheads against the wall or those who limited themselves to pressing it with a prudent occipital lobe. Before the eyes of Carvalho’s memory, Mexicans crawled on their knees towards the monastery of the Virgin of Guadalupe.» (Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, Milenio Carvalho, 2004).

«Returning from Sarnath, near the last ghat visited the day before, was the Panikkar restaurant, which the biologist and false colonel had recommended to them as one of the best specialising in the hybrid cuisine that arose from the British occupation: the cuisine of the Raj. […]

—Biscuter, you see that empires leave some positive traces, for example, in cuisines. The mole poblano, without going any further, would have been impossible without Spanish viceroys in Mexico. Likewise, the splendid British isolation made possible a cuisine of synthesis with the Hindu, the cuisine of the Raj.» Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, MilenioCarvalho, 2004).

«Look what’s happening in Chiapas. […] The killing of indigenous people by para-government butchers has justified the advance of the Army and an operation to harass the Zapatistas, that annoying revolutionary noise that got in the way of the “end of history” message perpetrated by former President Salinas and the United States. Look what’s happening in Chiapas because the ethical meaning of this end of the millennium is being played out there, as a symbolic referent, as an imaginary, if you will, of hope as a secular virtue.» (Spanish transcription of: Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, «Chiapas», El País, 12 de gener del 1998)

Letter from the insurgent sub-commander Marcos to Vázquez Montalbán, December 1997. Font: Biblioteca de Catalunya.

Interview of Vázquez Montalbán to Marcos. La Jornada, 16 February 2006.

«What impression does Marcos make on me? He seems to me to be a classmate almost twenty years younger than me and twenty years younger than the residual left from which I am trying to extricate myself as if it were a viscous swamp.» (Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, Marcos: El señor de los espejos, 1999).

«In March 2001, Vázquez Montalbán returned to Mexico as one of the many foreign intellectuals who welcomed the arrival in the country’s capital of the March of Indigenous Dignity, carried out by the EZLN. In addition to other events, the writer participated in the Intercultural Meeting, held on 12 March, at the Olympic Village in Mexico City, where he pronounced the following words at the end of his speech: “The Zapatista movement also showed what mirrors are for and what masks are for. The mirrors, to abandon the tricked mirrors, which power had placed to deceive or self-deceive, and reveal the naked reality of social situations as they really were. The masks curiously were in order to be seen. Until this movement put masks on the indigenous people they were not seen, they were the invisible exploited. When they put on masks, they were seen and, moreover, it helped to reveal that power itself, economic, political and cultural power, wore its own masks. Faced with all these issues, valuing that we are in the presence of a movement that has given rise to the culture of resistance of the 21st century, I already have an answer to the question asked by the aid workers, to the boys and girls who have come to see up close what Zapatismo means. I have the answer: we foreigners have come to Mexico to learn.» (in Ramón Lopes, El espejo y la máscara. Textos anexos al documental México Ida y Vuelta, Madrid, Ediciones Caracol, 2004, p. 136).

«The March of Indigenous Dignity, which departed from San Cristóbal de las Casas in February 2001, was also attended by Daniel Vázquez Sallés, son of Vázquez Montalbán, as a journalist. In his book Recuerdos sin retorno (2013), he recounted some of those moments shared with his father: “I remember the morning of our meeting in a station in Mexico City. I will never erase that smile of yours, followed by a laconic but sufficient phrase: “I see you are well.” I had travelled three thousand kilometres as an unranked member of the “zapatour,” the mobilisation led by twenty-three commanders of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) and the “subcomandante” Marcos. And despite the effort not without dangers, in which I include the threats of the paramilitaries, various bites and a very painful revenge of Montezuma, I did not get to surrender to the arms of the Sub, possibly because of the inability to generate in my body the endorphins of idealism. If I ever believed in anything, I no longer remember, and I never managed to see Marcos as an ideological beacon. […] When on Sunday we finished the caravan in the town of Zocalo turned into chaos with nonsensical touches, I went to the hotel where you were staying. When I arrived, you were eating with Saramago, Pilar, Serrat, Candela, Sabina. You invited me to sit at the table, but I was exhausted and fell asleep. At night and on account of our inability to fall asleep, you because of jet lag, me because of the comfort of the bed, we began to talk about the trip and I remember that I told you with sadness about my experience during the caravan with the Italian communists who had joined the Tutti Bianchi movement. […] The weight that, little by little, modern civil society is gaining germinated again after many years lost in limbo during those four weeks in which we toured Mexico following in the footsteps of SubcomandanteMarcos. Whether we were revolutionary tourists, or revolutionaries, or tourists, or travellers, or assholes, or naïve, or superficial players of a children’s role-play well, that is of relative importance.»

«Don Vázquez Montalbán was not our friend, he was our companion. “Fellow traveller,” he said in one of his writings. “Companion, that’s all.” we said then and we say now. I don’t know if that’s more or less for him or for you. For us it’s everything. I think Vázquez Montalbán had a deep respect for the reader. I think he questioned what to write, why and against what, and that he passed on those questions to reading: what is read, why and against what. And I think that, as a writer, he didn’t expropriate the answers from his readers. Contradicting the title of one of his books, he made no pamphlets. On the contrary, he made the word a window, and again and again, in his writings, he took pains to keep it clean and transparent. Apart from neoliberals, the Word usually attracts respect among those who confront them, that is, those who speak and write them, and those who read and listen to them. If someone were to ask me for an example that synthesized humanity’s resistance to neoliberal war, I would say the Word. And I would add that one of its most stubborn, and fortunate, trenches is the book. Although, of course, it is a very different trench because it looks extraordinarily like a bridge. Because whoever writes a book and whoever reads it only crosses a bridge. And crossing bridges is a trope of any anthropology manual that is respected, it is one of the characteristics of the human being. I say goodbye, but I would not like to do so without first declaring that, if someone asked me for a definition of Manuel Vázquez Montalbán I would say that he was, and is, a bridge.» (Fragment from Marcos’s letter sent to the tribute to Vázquez Montalbán that took place on 28 November 2004 at the Guadalajara International Book Fair.).

Promotional brochure of the trip to Mexico narrated by Jorge Herralde, which corresponds to the first trip that Vázquez Montalbán did to the Latin American country. Source: Toni Vall, Bocaccio. Donde ocurría todo, Destino, Barcelona, 2020, p. 13.

«Mexico is one of the most beautiful countries in the world, one of those countries that leaves you nostalgic and wanting to go back. I’ve told Encarna: when we lose the next civil war (which on this occasion would last three hours) I will go into exile in Rome or Mexico. […] For the craftsmanship, and not for the craftsmanship itself, but for craftsmanship as a symptom of the visual richness of a people. I would also go for the geography. The descent from Mexico to Cuernavaca with Popocatepel [sic] in the background is inimitable. Tasco[sic] growing on the mountains. All of the Yucatan, Cozumel, Can Cun [sic], Isla Mujeres. And I would go for the lobsters that you can eat in Puerto Vallarta at prices of sardines from Santurce. […] I would go to Mexico City to be able to walk through the colonial neighbourhoods of the Federal District: El Ángel, Coyoacán. To get hammered with margaritas in bars and anthropology in the museum of the capital. To be able to listen to Chavela Vargas live. For many things that do not belong so much to a possible tourist guide, they belong to the domain of intuition. I sense that Mexico could be my second country and that’s all there is to it. Too bad they sent Coronel de Palma as ambassador. I feel like I have been usurped. I want to be ambassador to Mexico. […] Encarna leaves me in the midst of a process of mental escape and when she re-enters my apartment I am in the Plaza Garibaldi in Mexico City fully immersed in destruction, music and the whiff of tacos.» (Sixto Cámara [Manuel Vázquez Montalbán], “Como México no hay dos”, Triunfo, 7 May 1977).

«The whales have not yet arrived or they are already leaving. It makes no difference. For a while they took refuge in the Sea of Cortez and now they look for their bread and plankton in other seas. In Cabo San Lucas the Pacific has opened up an ogival arch in the white rock. Not for nothing, the Californians call it the window of two seas. In Cabo San Lucas there are pelicans and sea lions. Precooked or pre-frozen gringo tourists, I no longer remember, and two single ladies who are from Puebla, but they could equally be from Cuenca, who wear a Nikon as if they were carrying a fan, and laugh, they always laugh so that the gringos forgive them for being from Puebla, being from Cuenca, being single, the fan. Or perhaps the Nikon. The ladies from Puebla, I mean from Cuenca, spot a warship and fan it for me, naturally with the Nikon. An American warship, that is, American in its flag and in its bow gun; American tout court in everything else, especially in its stern wind, and while the young ladies from Puebla, I mean from Cuenca, fan the sentry with their laughing photos of spinsters on vacation, the pre-frozen or precooked gringos stand firm so that their photographs are a visual hymn to the patrolling. Baja California is closer to the US dollar than to Mexico City, and it seems to one that the North American ship is like a dot on the i of this Finisterre. The whales will return, according to a secret pre-Columbian logic; sea lions smell of stale fish and are on the payroll for tourists, as are pelicans and pre-Columbian boatmen, all indifferent to the colour of flags and cannons. The Creoles of Puebla laugh and laugh among gringo couples who smile (Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, “Las señoritas del abanico”, El País, 27 March 1984. This text was the starting point of a eponymous story, included in Pigmalión y otrosrelatos [1987], and of the poems ‘Finisterre de California…’ and ‘La modernidad adosó un squash…’).»

«Finisterre of California / the whales have left / window of two seas / Cabo San Lucas / sad pre-frozen gringos / sea lions and pelicans / two young ladies from Puebla / or were they from Cuenca? / flutter with the fan / or was it a Nikon? / were photographing photographed a US warship / the bow gun / American the stern wind / photographed / caressed the bow cannon with the fan.» (Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, “Finisterre de California…”, poem included in Pero el viajero que huye [1990]).

«Modernity attached a squash / to the old pantheon of Trotsky / his slaughterhouse / is now a museum corner Vienna / Morelos / Coyoacán Mexico Federal District / with their backs to History / squash players fight / against age and excesses / of fat in the blood and eyes /others/[…] near / the ashes of Trotsky and Natalia Sedova / among myrtles and carnal flowers/ of a garden of insufficient aroma / they join in the dual failure of love / and history.»(Excerpts from “La modernidad adosó un squash…”, poem included in Pero el viajero que huye).

«I confess my nostalgia for Mexico when the occasion arises, and now that I can be here, even I am just passing through, I rethink my Mexican imaginary built on the basis of romantic revolutions, fundamental writers, Chavela Vargas, Lázaro Cárdenas, ten or twelve in a row indispensable for survival, all the taibos all, all the mixtures and landscapes and people of a country that is a forerunner of the future universal mixing of races.» (Transcription of Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, “México”, El País, 15 February 1999)

«Jorge Negrete was very deep inside the chest of the men and women of Spain. His machismo was ours, his whiskers ours, his virile melancholy ours, his reckless spirit ours. Few singers have been so sung, few have put in Hispanic throats more and better voice cracks. […] In the radio contests that looked for new stars, there appeared the little boy with the big lungs who with his hands wide open and his chin almost sunk in his Adam’s apple, started off with: Oh, Jalisco, don’t give up. / It comes from my soul to shout with heat. / Open your whole chest to shout out loud/How beautiful is Jalisco, upon my word! It came from the soul, from the cojones of the soul, as Miguel Hernández had been able to express the place where the Hispanic brain took refuge in a primitive pilgrimage of Cro-Magnon man. […] But it was nothing comparable to that cry of Mexican affirmation that vibrated with machismo in all the tumblers of the glassware of Spanish homes. I am Mexican, my land is brave […]. Negrete would have been nothing without his Hispanic gigolo moustache, without his somewhat cynical look and without that voice that came from the highlands of his chest. He was a very usable singer, because he came from one of the lands of the world where the most Spanish refugees had been taken in, where more and better Spanish refugees had laid down their mattresses and cast their nets, in search of the dream of the fugitive and fishing for the hungry. That is why here he was honoured as if he were a great recovered Creole chief (Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, Crónica sentimental de España, 1970).

«One of the main political problems of the new Spanish regime [Franco’s regime] was re-establishing diplomatic ties with Latin American nations. Many of the Spanish political exiles sought refuge in the Spanish-speaking republics and especially in Mexico, where they were excellently welcomed by President Lázaro Cárdenas. It is not surprising, then, that the official propaganda turned to the works of the Mexican composer Agustín Lara. The composer personally broke the political blockade and flooded the Spanish market with excellent songs, often directly inspired by motifs from Spain: “Madrid” was the most popular song for many years and glorified the new version of the capital of Spain built on the ruins of the republican resistance.» (Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, Cien años de canción y Music Hall, 1974).

«[Chavela Vargas] is perhaps the best popular Spanish-speaking singer, and she has achieved it as these things are achieved: based on a lot of alcohol, memory and desire. […] Chavelabelongs to the communion of blues singers, an irritating pressure group that gets you down from time to time, especially when the night complicates loneliness. So far, Chavela is little known in Spain. I heard “Macorina” for the first time in 1965. […] What a song! It’s the most beautiful erotic message of all popular poetry. […] I will only say that from time to time I play it, when I run out of real or mental loves and need that essential dose of self-pity to continue being a statue of salt before the forbidden cities.» (Sixto Cámara [Manuel Vázquez Montalbán], “Chavela Vargas“, Triunfo, 14 July 1973).

«When I find you / in the storage room of the world / Chavela / I will be indiscreet / I would like / to know what happened to your Macorina / if you knew what to do / of that smell of woman / mango and new [sugar] cane / I forgive you / for the women you have taken from me / in exchange for you singing to me / forbidden bodies / hot as danzónes / cinnamon colour moistened by desires /[…] the old Macorina no doubt ill-loved / in the years when it was not yours / or mine / but a progressively absurd body / abandoned by guitars and laments.» (Excerpts from “Ponme la mano aquí“, poem included in A la sombra de las muchachas sin flor [1973]).

«From the ancient rituals, the food and the rite of the day of the dead are preserved, a cultural variant of the ancestral custom of providing food to the deceased so that they arrive well-nourished on the other shore. But in Mexico the Catholic-pagan melting pot has given rise to a picturesque gastronomic and funerary festival that today is a must-see for both the anthropologist and tourist. No matter how humble the house is, and mainly in the states of Puebla, Mexico, Oaxaca and Michoacán, on 31 October and 1 and 2 November, offerings are made to the dead: sweets, fruits and dishes as succulent as they are different. Christianity contributes to the festival with its sacred imagery arranged on an altar, and paganism contributes with a well-laid table with black glazed clay crockery, full of these stews: molewith guajalote, pork or chicken, pumpkin dessert, tejocote, guava, all sprinkled with toasted sesame seed, as well as covered with a sweet bed of blue, purple or red corn. The pagan picture is completed with fruit and sugar skulls with the eye sockets covered with brightly coloured papers, adorned with sugar filigree and the names of dead loved ones written on the forehead. The playful-funerary inventory is impressive: skull-shaped breads and skeleton leg bones, egg bread called hojaldres or “pan de muerto“.» (Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, Contra los gourmets, 1985).

«The Mexicans have a special talent for cocktails. Anyone who hasn’t tried margaritas or daiquiris made by Mexican bartenders doesn’t know what’s good. […] Although it may seem like a contradiction for the palate and a desperate challenge in the heat, I recommend that after warming up the fundamental muscles with piña colada, the visitor to the Yucatan surrenders not to the excellences of the local cuisine, one of the most elaborate in the world, but to the brutality of a mestizo stew, son of a conquering father and Yucatecan mother.»(Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, ‘Piña colada’, Interviú, 10 January 1980).

«First of all, corn, for the taste and variety of use. Then, when I made a road trip of Mexico, my first great impressions were made by the mole poblano in the place where they prepare it. That combination must have been inspired by some god to a nun. A fun-loving god, not a Christian one. Mole is an imagined dish in a state of grace.» (Interview by César Güemeswith Vázquez Montalbán, La Jornada, 18 February 1999).

«While waiting for Parra, Carvalho thought of other poets of odd trades. Emilio Prados working as a monitor for children at break time in a school in his Mexican exile. Or that poet who ended up as a kindergarten teacher in Tijuana. Carvalho met him at a bar on the border drinking tequila with salt after tequila with salt and, between glasses, half a sip of water with baking soda.

—Until Franco dies I’m not going back. It’s a moral fact. Even though I’m a nobody. But I have my pride. I appear in the youngest anthologies before the [Spanish Civil] War. Justo Elorzía. You’ve never read anything of mine? I’ve barely been able to move to publish again. From Argeles concentration camp to Bordeaux, then the ship, Mexico. And as soon as I arrived, I fell on my feet in Tijuana. A temporary job at a school. Temporary. Thirty years, my friend. Thirty years. Every time I hear a rumour that Franco was sick or about to fall, I stop shaving, pack my bags and don’t change the sheets on my bed. So that everything would push me to leave here. A few months ago I despaired. I have twenty books of unpublished poems, friend. I went down to Mexico to talk to Exprésate, the Era editions. I know Renau a lot, the poster painter. Now he’s in East Germany. Well, the girl from Era is the sister of a son-in-law of Renau. They proposed me to make an anthology. Do you hear? An anthology of books that have never been published. It’s like killing them one by one .» (Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, La soledad del mánager, 1977).

«From the shelves still full of books he extracted Las buenas conciencias by Carlos Fuentes, a Mexican writer whom he had met by chance in New York during his time as a CIA agent and seemed to him an intellectual who lived at a sideways angle, at least he greeted you sideways on. He had shaken his hand as he looked westward. Such cavalier treatment had been received by Carvalho without Charro knowing that he was in the CIA, knowledge that at least would have justified his attitude for ideological reasons. But Carlos Fuentes had no reason to barely shake his hand and continue to look west. They were in the house of a Jewish Hispanist writer named Barbara, whom he was watching by order of the State Department, because it was suspected that in her house a clandestine landing in Spain was being prepared to kidnap Franco and replace him with Juan Goytisolo. The Spanish embassy cultural attaché was telling him surreptitiously about the background of the staff that were moving through that party. […] Of special interest was a Spanish writer who tried to convince anyone who wanted to hear him that the best dish of Spanish cuisine next to any dish of Arab cuisine was a fabada[…]. Carvalho wrote a report for the CIA in which he tried to show that they were harmless people who lacked affection, like almost everyone. Or it had not been exactly like that, but the truth is that Carlos Fuentes had treated him contemptuously without any justification and his novel was going to serve as basic combustible material for the campfire that was going to warm his house and soul.» (Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, La Rosa de Alejandría, 1984).

«—Don’t exaggerate, boss. If the plane crashes, much more would be lost than the photographs. Have you been to Mexico?”

—Yes.

—Is it such a sick country as they say?

—It’s a beautiful country.»

(Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, “La guerra civil no ha terminado”, Historias de política ficción, 1987).

«The next day some cases were opened and remained for a long time before the Western Wall, recording the variety of costumes of the Jews who were going to lament by means of a ritual resemblance of moaning, although there were those who almost crashed their foreheads against the wall or those who limited themselves to pressing it with a prudent occipital lobe. Before the eyes of Carvalho’s memory, Mexicans crawled on their knees towards the monastery of the Virgin of Guadalupe.» (Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, Milenio Carvalho, 2004).

«Returning from Sarnath, near the last ghat visited the day before, was the Panikkar restaurant, which the biologist and false colonel had recommended to them as one of the best specialising in the hybrid cuisine that arose from the British occupation: the cuisine of the Raj. […]

—Biscuter, you see that empires leave some positive traces, for example, in cuisines. The mole poblano, without going any further, would have been impossible without Spanish viceroys in Mexico. Likewise, the splendid British isolation made possible a cuisine of synthesis with the Hindu, the cuisine of the Raj.» Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, MilenioCarvalho, 2004).

Contributions

To learn more about Vázquez Montalbán and Mexico

Weselina Gacinska, «Los movimientos indígenas y la globalización en los reportajes de Manuel Vázquez Montalbán», MVM: Cuadernos de Estudios Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, 2020, 5, 1, p. 26-45.

José Colmeiro, «Libros como puentes: Bibliografía latinoamericana de Manuel Vázquez Montalbán. Archivo en construcción», MVM: Cuadernos de Estudios Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, 2020, 5, 1, p. 146-173.

Sergio García García, «Los puentes entre Manuel Vázquez Montalbán y el EZLN: cronología e intercambio textuales (I)», Philobiblion: Revista de Literaturas Hispánicas, 2021, 13, p. 37-52.

Sergio García García, «Los puentes entre Manuel Vázquez Montalbán y el EZLN: cronología e intercambio textuales (II)», Philobiblion: Revista de Literaturas Hispánicas, 2021, 14, p. 75-92. 05

Sergio García García, «Manuel Vázquez Montalbán en México», cicle de conferències de literatura llatinoamericana avui, 6 de desembre de 2021.

Documental Marcos: «Aquí estamos» (2001), directed by Gianni Minà.

Sergio García García, «Manuel Vázquez Montalbán en la prensa mexicana (1979-2003)», La Colmena, 2023, 118, pp. 25-40