GASTRONOMY

Text and selection of content: Rosi Song

Gastronomic reference

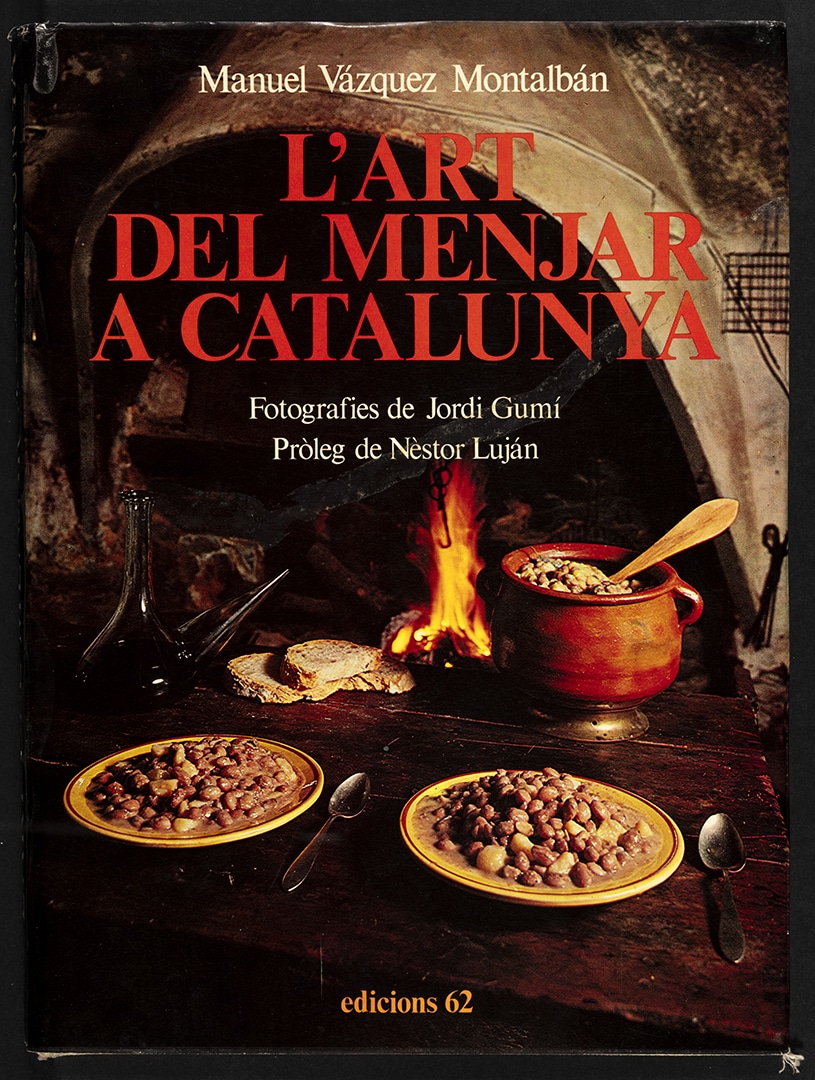

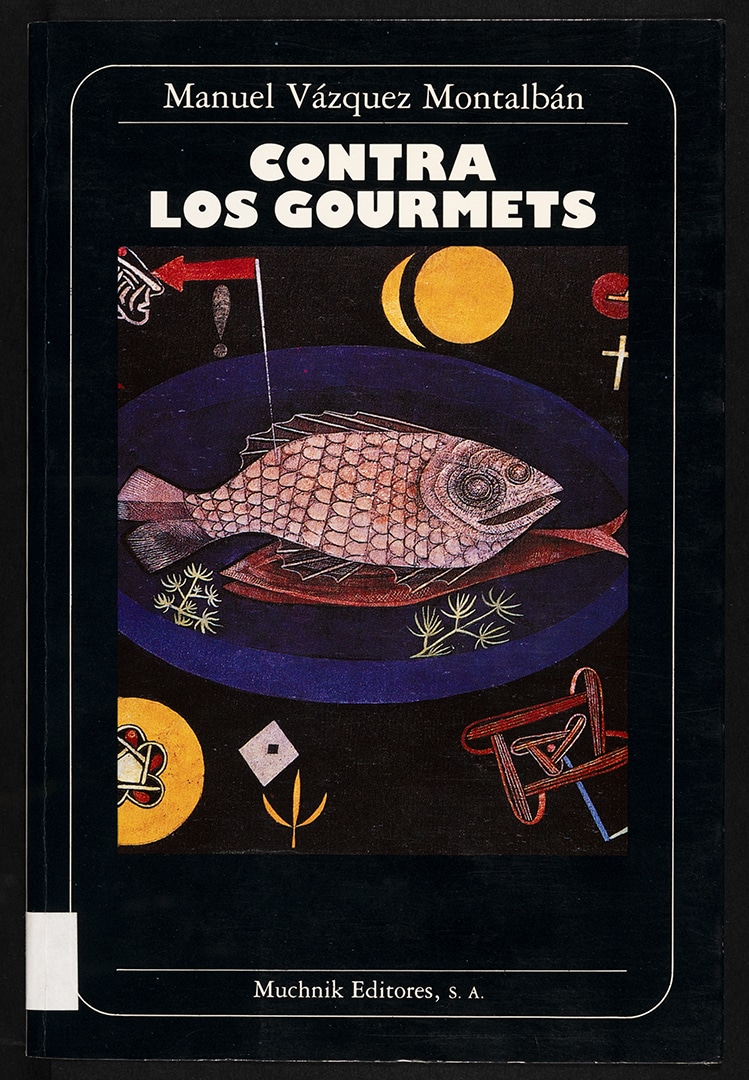

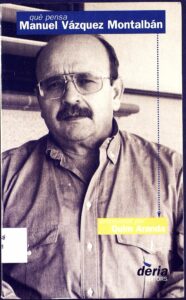

Manuel Vázquez Montalbán has been a fundamental authority in the Spanish gastronomic landscape since the first years of the TransitioManuel Vázquez Montalbán has been fundamental to understand the Spanish gastronomic landscape from the early years of the country’s political transition to democracy with the publication of his L’art del menjar a Catalunya (1977) [The Art of Eating in Catalonia] and the creation of his world-famous literary detective character, Pepe Carvalho. A detective who combines crime solving with his love for food, he is an extraordinarily knowledgeable and talented cook. It would not be an exaggeration to suggest that since his appearance in the literary crime scene, all detectives seem to have developed their own culinary obsessions or feel the need to make food related observations. Perhaps the most accomplished food writing that reveals Vázquez Montalbán’s experience and gastronomic intelligence is his Contra los gourmets (1990) [Against Gourmets], where in chapters like “Hambre, experimentación y memoria” [Hunger, Experimentation and Memory] or “El hombre es lo que come”[A Man is What He Eats], he revisits the topics that he frequently writes about and which emphasize, again and again, cooking as an important cultural element but also a cultural event.

In his case, memory, identity, and politics are closely linked to food and eating, from the dishes of his early childhood, the nostalgia of their taste and the places where they used to be served. Food, in his writing, is deeply connected to everything that surrounds us and has much to teach us about our history, our injustices and our taste. He wrote, for example, about the Spanish cured ham: “The jamón is more than a mummified leg of a dead animal that is edible, it is more than a gloriously mummified leg of a glorious Iberian pig. The jamón is part of our Spanish imagery about abundance as it is forgotten that the jamón was used as proof of Christianity, as moors and jews would not touch pork. A good Christian was able to sink his or her teeth in its flesh and turn the experience into one more proof about the existence of God in times when it was most needed.”

Selection of texts

Vázquez Montalbán had already anticipated what Food Studies scholars research and teach today, that “food turns into culture the moment it is linked to space: the place where it is cooked, which is, originally, where it was consumed” (Against Gourmets). We could call him a visionary of the concept of foodscape, an intellectual writer who paid attention to his natural landscape, but also his cultural and political one, who offered an intelligent reading of the cooking of the Iberian Peninsula, vindicating its value, especially that of Catalonia, in his foundational text, L’art del menjar a Catalunya [The Art of Eating in Catalonia] (translated into Spanish as La cocina catalana [Catalan Cuisine] in 1979). This text, with an introduction by another famous gastronome, Néstor Luján, detected an incipient culinary revolution that would soon transform this region into a leader in the culinary world, a status and international prestige that it still maintains today. At the same time, considering his diverse culinary interests and his influence on and friendship with the founders of the Slow Food movement, it is not surprising that his name continues to be associate with movements and initiatives of social action like Kilómetro 0 [Eat Local]. His gastronomic interest goes beyond the region of Catalonia, covering all corners of the Iberian Peninsula, and which are collected in his five-volume collection of the Carvalho Gastronómico series [Gastronomic Carvalho Series]. He demonstrates his culinary knowledge through the recipes collected for the collection as well as his knowledge about Spanish wine.

Vázquez Montalbán had already anticipated what Food Studies scholars research and teach today, that “food turns into culture the moment it is linked to space: the place where it is cooked, which is, originally, where it was consumed” (Against Gourmets). We could call him a visionary of the concept of foodscape, an intellectual writer who paid attention to his natural landscape, but also his cultural and political one, who offered an intelligent reading of the cooking of the Iberian Peninsula, vindicating its value, especially that of Catalonia, in his foundational text, L’art del menjar a Catalunya [The Art of Eating in Catalonia] (translated into Spanish as La cocina catalana [Catalan Cuisine] in 1979). This text, with an introduction by another famous gastronome, Néstor Luján, detected an incipient culinary revolution that would soon transform this region into a leader in the culinary world, a status and international prestige that it still maintains today. At the same time, considering his diverse culinary interests and his influence on and friendship with the founders of the Slow Food movement, it is not surprising that his name continues to be associate with movements and initiatives of social action like Kilómetro 0 [Eat Local]. His gastronomic interest goes beyond the region of Catalonia, covering all corners of the Iberian Peninsula, and which are collected in his five-volume collection of the Carvalho Gastronómico series [Gastronomic Carvalho Series]. He demonstrates his culinary knowledge through the recipes collected for the collection as well as his knowledge about Spanish wine.

Contributions

Audiovisual

Con las manos en la masa – Manuel Vázquez Montalbán | RTVE Archive. 1984.