Futbol Club Barcelona

Text and selection of content: Jordi Osúa

Sport lover

Manuel Vázquez Montalbán was in the habit of using the adjective “culé” (Barça supporter) to define himself. This interest in sport in general and in FC Barcelona in particular is reflected both in his life and in his work. Some of his essays, novels, television scripts and numerous journalistic articles are devoted to reflection on the sporting phenomenon for which he gained great international recognition. Despite his limited sports education, he played some sports, but above all he followed football, cycling, tennis and boxing on the radio and on television.

His Barça style is rooted in the sentimental landscape of his childhood in the Raval neighbourhood, in the legend of the Barça of the Five Cups and in going to see matches, first, in the Les Corts stadium with relatives and, later, in the Camp Nou with a group of intellectuals of the anti-Franco left.

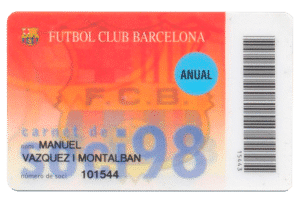

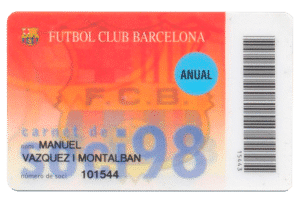

His apt and original explanation of what is “more than a club” with the phrase “unarmed symbolic army of Catalonia” made a great impact. He participated in various projects of the club and made known its political and social significance beyond our borders. Always eager to know the results of his team from any corner of the planet, he finally decided to become a shareholder. The tribute held at the Camp Nou on the day of his death and the creation of the “Manuel Vázquez Montalbán International Journalism Award” are a testament to the importance of his figure and his legacy as an intellectual, sports journalist and culé fan.

MVM Sports Library

Selection of texts

A bad sports education: “Our bad sentimental education became bad sports education, worse, impossible sports education. Only in schools from the urban waist up did they know what a stopwatch was for and years later, when the educational authorities tried to impose “sport” in neighbourhood schools, located in flats and with no other possible teacher than the principal’s skinniest daughter, the one who did the business was the nearest carpenter, responsible for making a vault, for example, by eye or ear, with the obvious risk that an entire class of schoolchildren like us would lose on their backs the future possibility of a career as Japanese sex athletes”

“Opening your eyes to the sense of muscle in the post-war period was not stimulating. The only sports facilities for the common folk were the vacant plots opened by the bombs, improvised football fields for balls made of rags, tin or rubber and, instead of showers, some hydrants or those fountains of Barcelona” (“Crónica sentimental de la musculature”. in: Olimpiada Cultural, 16 November 1990. No pagination.).

Football on vacant sites on the outskirts of the city: “When we were kids, between Barcelona and l’Hospitalet there were twenty kilometres of vacant sites. In Montjuïc, the Expo exhibition halls that had collapsed were esplanades where we went to play football” (“Barça i integració” in: Amb blau sofert i amb grana intens. Cent anys del Barça. Barcelona: Proa, 1999, p. 152).

Football among paving-stones: “Marcet, a very fine winger who once kicked a ball that someone gave him in a street (you could play football in the streets then), a mate of knock-abouts. Marcet took the ball, passed it from one foot to the other, flipped it to one shoulder, then to the head, dropped it on the tip of one foot… in short, he showed ball control. After the event there was a division of opinions. The most radical wing of the little band gathered there reproached the one who had passed the ball to Marcet for fraternising with the enemy. But, fortunately, the moderate majority prevailed and Marcet, despite being an Español supporter, entered our mental Olympus and during the years that remained of friendship and adolescence we remember that day when Marcet passed through our cobblestone stadium.”(“Enemigos para siempre”. El País, Deportes, 29 November 1992, p. 48).

The Flors de Maig 11-a-side football team: “The Flors de Maig (Mayflowers) team was made up of people who worked with publishers (Planeta, Salvat, Enciclopèdia catalana, Larousse), as well as some young university students. Two teams were set up, I don’t know how, one was the Mayflowers, which was called Atlético Marxista and we were in red, and another was the Real Acrata who were in black and was the team we normally played against. Here there were many diverse people, even a professor who was vice-rector of the University of Barcelona and Enric Fusté, financial advisor to Manolo and who appears in Carvalho, Jordi Borja, Solé Tura, it was a mixture of people from the publishing and the political worlds. We normally played on Saturday or Sunday mornings. I remember a significant anecdote. We went to play in La Verneda, in Poblenou, a working-class neighbourhood, adjacent to the ground of La Bota. We were playing and there was one thing that was striking even though we didn’t lend it any importance was that looking at both teams possibly three-quarters of the players wore beards, because it was a time when long hair was in style, and someone in the crowd said “these teams spend less on barbers than the Russians on catechisms”. It was striking because it wasn’t the run of the mill teams of young people in the neighbourhood, but people from the publishing world, usually left-wingers, who ended up calling and saying we need eleven to play… I remember these matches that were held from time to time, I remember taking part two or three times a year, mostly in the spring.” (testimony of Borja de Riquer).

Futsal team with the colleagues of the CAU magazine

Centre-forward position

MVM: I was a centre-forward because I was a bit heavy, I led the charge…

E.V.-M: Who were you like?

MVM: It was what they called the “Spanish fury”. I was a buffer, but from time to time I scored goals»

(«Barça i integració». aavv. Amb blau sofert i amb grana intens. Cent anys del Barça. Barcelona: Proa, 1999, p. 153)

«I remember that at that time if you wanted to have a place to hold meetings you could only join the Youth Front or the local Catholic Centre. And I signed up for the Catholic Centre of the El Carme parish.

By the way, I often bumped into Benet and Jornet there, and Antoni von Kirchner. They would meet there to play ping-pong.»

(Quim Aranda. «Què pensa Manuel Vázquez Montalbán». Interviwed by Quim Aranda. Barcelona: Dèria Editors, 1995, p. 27)

Physical exercise in the Centro Gimnástico Barcelonés

Poem “Bíceps, tríceps”

“Bíceps, tríceps…

He had died

when attempting to do a handstand

on two lacklustre stools,

drops of lemonade

or indentation, sweaty hands of couples

between one Sunday dance and another

on the outskirts, picnic areas

with yellow papers and purple

garlands

But no one silenced the squeal

of the pulley, nor did it stop spinning

on the fixed bar, not did the vault rear up

at the reckless jumps of artistic

gymnasts

and in front of the mirror, biceps

triceps with rusty weights, deficient

neighbourhood gym equipment

improve the race

expensive project of informative leaflets

biceps and triceps from seven in the morning,

turners, die makers, carpenters

even heirs to grocery stores,

dry cleaners, electrical accessories,

nuts

the son of the local pharmacist raised

the rope with a half-iron unassisted

and in the summer

I made love on the sand with disenchanted Swedish women

white thighs and small breasts

somewhat sad, somewhat rich, somewhat frigid in Sweden,

in Spain dazzled by the sun, Spain

is different and the biceps of stallions

warm as a whispered song – the girl

from Puerto Rico, for whom do you sigh?

They sighed.

rhythmically -breathe in-breathe out-biceps-triceps-

or exchanged obscene words, obscene gestures

with girls somewhat made up, fishnet stockings

and blue, pink, home-knitted cardigan,

They learned cutting and tailoring in the windows

close, uselessly blushing because of an

unforeseen sex peering from the window

between biceps

and triceps, raised curious eyes

towards the terrace

where serious, like vegetarians,

the supporters of Swedish gymnastics,

high school children, round-bellied paterfamilias,

Aspirants and Instructors of Accion

Catolica, men with principles and readings

graduates, Muller, Swedish gymnastics

and Health, rites, one two, one two or ow, or ow,

the teacher raised his hands towards the mist,

on the grey tiles of unwashable green beans,

under the TV aerials, the cry of distant sirens in the port, in the factories

«Las ocho y media de la mañana en la Ciudad Condal». Una educación sentimental. Barcelona: El Bardo, 1967, p. 24-26

Boxing during his childhood: “We all belong to the country of our childhood and I am from the nineteen-forties. There was a young boxer who had won the golden glove before the war and who tried to throw a hard punch to gain the victory that he would never achieve.” (Luis Lopez Doy (dir.). Manuel Vázquez Montalbán: el éxito de un perdedor. Madrid: Televisión Española, 1997). If we can obtain the video, it can be included as an audiovisual resource.

Young Serra: “Another name I think is important is Young Serra, the name of the boxer who appears in El Pianista and is also the main character of the short story “Desde los tejados”, in “Historias de familia”. (…) At that time there was a featherweight boxer in Spain called Young Martín and he was scrawny, like half a kilo of boxer, but he won fights, he was the European featherweight champion.” (Georges Tyras. Geometrías de la memoria. Granada: Zoela, 2003, p. 143-144).

Young Serra’s training in El pianista:

“The other one runs over the burnt bricks, marked by the urine of the dogs that have left behind their shit burnt by the suns that the dancing runner uses as obstacles for the fencing-like tension of his steel legs, like steel cables, Andrés comments mentally when he sees him leap and jump and make movements to pivot and strike his own shadow.

You’re going to make yourself ill if you keep training like this and eating the rations they give us, Young. Stop now, damn it, Young.

But Young, Young Serra, “golden glove” champion of the bantamweights of Barcelona, flits around Andrés and even pretends to hit him, bringing his fist two centimetres from his chin.

“One of these days you’re going to hit me.” (El pianista, p. 87).

The cycling epic: “We love cycling those who since the time of Bernardo Ruiz turned it into an epic cutout on the school desk, and the giants of the route were just that, the giants of the route, without anyone asking them for explanations about gasoline or wood gas, in the case of the Spaniards, who guzzled it down” (“The Tour” El País. 9 June 2001. Last page).

“I wish there were a Tour every month, because I know there are other important stage races, but the Tour is the true religion and since the times of Bernardo Ruiz, Koblet and Kubler, I live a whole year obsessed with the Tour and when I am no longer in this supervisory role one of my sadnesses, if I take any with me, will be not knowing what the Delgado of the day has done in the Tour” (“Pericomania” Interviú. No. 690. 1 August 1989. p. 122).

Football on the radio: “The comeback of Matías Prats is a bit like recovering a childhood. I remember those football broadcasts in which the voice of Matías Prats managed to turn Gonzalo III into Siegfried, Basra into the real monster of Colombes and Gainza into a fox impossible to hunt, even the English abstaining” (“The return of Matías Prats” El Periódico. 30 May 1981. p. 39).

Football on television: “And one has an elephant’s memory, an immense memory in which one keeps the collective celebratory tone of the victory over England in 1950. They were the same faces, the same vented frustrations, the same desire to give meaning to life and history, since it is not given by the daily exercise of living. I watched the 1950 match surrounded by Spaniards who were diverse in their ideology” (“Gol, gol, gol, gol, gol, gol” in: Triunfo. No. 774. 10 December 1977. p. 20).

“I have thought about my most immediate epic horizons and a football league awaits me that I don’t intend to miss. As for TV, I only watch movies and football matches regularly, everything else is a gerund or has an absolute majority.” (“Saviola y Zidane” Interviú. No. 1319. 6 August 2001. p. 106).

Live football: During my long stay in the Americas, I received a privileged invitation: to attend a Boca Juniors match in the presidential box. It is not a box in the European manner, but glazed, a protected window open to the spectacle of this sweetshop located in one of the most working-class and, in a sense, down at heel neighbourhoods of Buenos Aires” (“Boca, algo más que un club” Interviú. No. 1181. 14 December 1998. p. 114).

The feats of Santana: “I like tennis and I like it thanks to television because I belong to the large number of Spaniards who discovered this sport in the sixties, thanks to the television broadcasts of the deeds of the great Santana” (“Tennis and television” El Periódico. 27 November 1982. p. 43).

The pen-name Luis Dávila: “I thought that name [Luis Dávila] reminded me of a sports journalist. At that time no Spanish intellectual was able to talk about sport because that seemed to them a mediocre, minor thing, and to report on sport or do sports criticism it would seem as if the rings fell from his fingers, so I looked for a pseudonym that seemed to me to sound like a sports writer” (Roberta Erba. Los pseudónimos de Vázquez Montalbán, interview held on 6 June 1994).

The duels with Javier Marias: “Whenever a Barcelona-Real Madrid or vice-versa classic came around, they would nearly always drag me and Javier Marias out of our autumn barracks to show our heart so white or so blue and claret” (“Adiós, Barça, adiós”. El País. 13 October 1999. p. 64).

Publications about the Barcelona Olympic Games: “As the Olympic Games grew closer, I received journalists and social theologians from all over the world who sought in me a critical Virgil of the city and the relationship between the city and the games” (“El loro y los Juegos Olímpicos”. Profil. 14 September 1992. No pagination).

Le Monde Diplomatique and football: “The fact that a publication conventionally so serious and so aware of what is necessary news as Le Monde Diplomatique should devote a monographic issue to football just a few months ago shows the importance that this secular godless religion is acquiring, one that is endowed with a rigorous ritutal and worrying ends. In the piece that Le Monde Diplomatique asked me to contribute, I took as my starting point the evidence that Berlusconi would probably never have become prime minister of Italy without the help of the Milan of Van Basten, Gullit and Rijkaard” (“El fútbol, una religión sin Dios”. Interviú. No. 1124. 10 November 1997. p. 122). This article was published in August 1997 with the title “El fútbol: una religión civil en busca de un Dios (football – a civil religion in search of a God”.

L’Équipe and sport: “The newspaper L’Équipe asks a series of politicians and intellectuals to state their views about the meaning of sport at the end of the century, the end of the millennium”. (“L’esport”. Avui. 18 December 1999. p. 19).

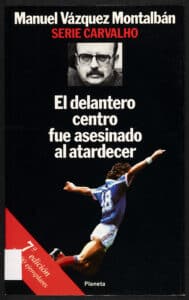

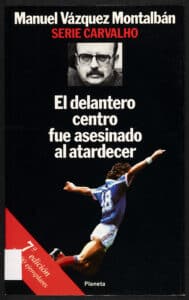

“There was Carvalho in front of the cemetery gate, in a silent dialogue with the old glory, a piece of the collage of his childhood when they reproduced it as a slogan of the posters announcing the Sunday matches, hooked behind the windows of the most crowded establishments on the street: the mandatory bakery of mandatory post-war black bread or the dry cleaner’s where the four daughters of Mrs. Remei bloomed. Four breasts in bloom that roamed the street under the rain of lewd whistles, co-owners of flesh unbecoming of a post-war of a general and equally mandatory rationing” (El delantero centro fue asesinado al atardecer. Barcelona: Planeta, 1988, p. 141).

Political and social identification: “In the Raval neighbourhood and in the Barrio Chino, the native Catalan workers and those descended from migrants were mixed together. And to cohabit precisely means to know that there is one who is different, because they talk differently and they have different habits and customs, other symbolic referents that you feed on little by little, such as Barcelona football club, for example.” (Georges Tyras. Geometrías de la memoria. Granada: Zoela, 2003, p. 40-41).

“When at school we commented on the results, I already knew that it was a team that was, let’s say persecuted, because it had been a Catalanist team, the Francoists had executed its president in 1936, and a Barcelona team had gone around the world playing matches and promoting the Republic, just like another from club in Bilbao; Some of those footballers were later exiled. You assimilated all that in a diffuse way and took it on board as a sign of participation in the country” (Georges Tyras. Geometrías de la memoria. Granada: Zoela, 2003, p. 41).

FC Barcelona in his sentimental education and cultural admixture: Poem Visualizaciones sinópticas (end of the poem “Visualizaciones sinópticas”, included in Escritos subnormales).

The songs of his childhood: “In a neighbourhood now called Raval, it even has its own Rambla, and which then was called Chino or disrict V, it was impossible to sing The International or La Varsoviana or Els segadors, songs for Republican times. But we did sing in pure ‘charnego’ [Catalan influenced by Castilian as spoken by economic migrants from other parts of Spain – pejorative]: If a dove comes to your window/treat it kindly because it’s from Barcelona/If a little owl comes to your window/hit it with a stick it’s from Espanyol. Or we would recite: There are six things in this world that shine brighter than the sun / the six cups of Barcelona and the shit of Espanyol (“Kubala, entre Gamper y Cruyff”. El País. 18 May 2002. p. 42).

Kubala: “I was impressed by Kubala, the first wizard of the ball for those of us who had not seen Samitier play” (“Manuel Vázquez Montalbán”. Pere Ferreres. Cien años azulgrana: entrevistas a la sombra del Camp Nou. Madrid: El País-Aguilar, 1998, p. 203).

The Barça of the 5 Cups: “When I got out of that strange club (jail), I went through a period of football non-belief, until I asked myself: which is more stupid, to believe in Basora, César, Kubala, Moreno and Manchón or in Carrillo and el Guti? I decided to believe in Barça and to study very closely the politics that affected me, but always, always, based on the evidence that neither history, nor life, nor Europe were what we deserved” (“Credo”. El País. 21 May 1992. p. 54).

To Les Corts with some family members from the neighbourhood: “I went many times with my relatives to see “Barça” play at the old Les Corts ground. There were seasons when I didn’t miss a match” (“Barça, Barça, Barça”. Barça. No. 802. 30 March 1971. No pagination).

“I used to go to Les Corts [football ground] because a wholesaler who was a part relative of mine had a member’s card. ”I didn’t need it and I generally sneaked into the zone where the crowd pushed en masse” (“Barça i integració”. Amb blau sofert i amb grana intens. Cent anys del Barça. Barcelona: Proa, 1999, p. 156).

To the Camp Nou with a group of friends and his father-in-law’s member’s card: “I stopped going to the stadium for a several years. From 1964 I started going again, and since then I have renewed my father-in-law’s member’s card every year; he has number eight thousand and something. My wife also has a really low member’s number. I still have my father-in-law’s member’s card because he can’t go to the ground any more and he would be very upset if I were to take out a new one, as he is a real “culé” (a diehard Barça fan). I go to the “Camp Nou” with my wife and a group of friends, who are lecturers at the Autonomous University – Sergi Beser, Pep Termes, Jordi Argenté…” (“Barça, Barça, Barça”. Barça. No. 802. 30 March 1971. No pagination).

From the terraces to the President’s box: “When I started going to football, I used to go to the Les Corts ground; now I go to the upper main grandstand and, unlike Mr. Baret, I have completely forgotten those times, because in the grandstand you are much more comfortable and, on the other hand, it is one of the few places in the country where the police treat you with respect” («Vázquez Montalbán, president del Barça?». Oriflama. No. 93. March 1970. p. 25).

The admiration of technical and skilful players: “I’ve burst many a blood vessel for Reixach and for Suárez. The Barça crowd also liked the players with the foreheads tinged red with martyrdom, those who sweated the shirt, and barely appreciated those who have fun playing” (“La esquizofrenia del entrenador”. El País. 22 October 1995. p. 14).

“I’m seasoned by life and football fields and I, who have seen Kubala dribble with his hips, Eulogio Martínez dribble sideways, Di Stefano reinvent the football field with his imagination or disguise himself as a post, Cruyff score goals with his fringe, I regretted the other day never wearing – but never – a hat to take off when I saw Romario leaving Osasuna’s goalkeeper beaten and lonely with a perfect chip”. (“Esplendor en la yerba”. El País. 10 October 1993. p. 44).

“And now I adore De la Peña, who is brilliant and bonkers. I remember one day, Robson was the manager, when Ivan tried a great pass, Robson came off the bench to see it. When he missed, he turned to the bench with his hands on his head to show that he was mad. But Ivan tried it again later and he got it right” (“Barça i integració”. Amb blau sofert i amb grana intens. Cent anys del Barça . Barcelona: Proa, 1999, p. 146).

The post-match discussions in his home in Les Corts: “There were also people in the PSUC who enjoyed football, like Pepe Termes or Fontana, and every time we went to the stadium, after the game we would comment on the plays at home, and I realised that I wasn’t so heterodox. (“Manuel Vázquez Montalbán”. Pere Ferreres. Cien años azulgrana: entrevistas a la sombra del Camp Nou (A hundred years of blue and red: interviews in the shadow of the Camp Nou stadium). Madrid: El País-Aguilar, 1998, p. 203).

“And when the match was over, the meetings we held at home, with Borja de Riquer, Pep Termes, Josep Fontana, Jordi Argenté, and sometimes Jordi Solé Tura, among other centre-forwards. There was a lot of drinking, a lot of arguing, and little was resolved.” (Daniel Vázquez Sallés. “Más que un adoquín”. El País. 1 June 2003. p. 51).

Supporting Barcelona, a secular religion: “However, I have always said that I preferred to be religious in football so as not to have to be religious in love, in politics, or in religion. Each to his own faith. Like Serrat, I believe in Basora, César, Kubala, Moreno and Manchón” (“El Barça és el nostre club”. Ramon Barnils (Ed). Decàleg del culé (The Ten Commandments of the FC Barcelona supporter). Barcelona: Columna, 1992, p. 17).

“Impossible to forget that the celebration of the Centenary of Barcelona FC has begun, an institution that I declare I support for the same reasons that Joan Manuel Serrat does. We are both kids from the block and we became Barça supporters because in the shops in the country when we were boys there were posters depicting how Samitier would dribble past a player, any player, of Español. We both became Barça fans thanks to the deeds of Basra, César, Kubala, Moreno and Manchón. And we still are because Barça was the symbolic army of an idea of what it means to be Catalan that is of the people, secular, with no need to go on a pilgrimage to any mountain other than the terraces of the Camp de les Corts or the Camp Nou” (“El Barça del desencuentro”. El País. 28 November 1998. p. 46).

“We agnostics have to be given a chance to believe in something, and I take it by believing firmly in the revealed truth of Barcelona Football Club.” (“L’esport”. Avui. 18 December 1999. p. 19).

Always with an eye on his team’s results: “And the thing is that, since childhood, an important part of my calendar has been prefixed by national football competitions and the role that my favourite team played in them. I know that the worst thing that can happen to an intellectual is to know which part of his brain has a limp, so it is in football as in politics. There’s nothing we can do about it. My fate was decided long ago” (“La Copa”. El País. 21 June 1985. Last page).

“I confess that I sometimes, when I have thought about death, fretted about the impossibility of knowing how Barça would do in the League. For me, dying meant never again to know who had won the League, and to fear the last critical-biographical comment that Rafael Conte would doubtless dedicate to me in EL PAÍS” (“Volver a empezar”. El País, Deportes. 28 August 1989. p. 12).

Following Barça’s matches on the radio: “The first time that Barça lost the European Cup, I was in prison, doing my anti-Francoist duty, but attentive to the football results that were broadcast on the loudspeakers in the prison yard of the Modelo” (“Credo” in: El País. 21 May 1992. p. 54).

“Whatever happens I will find out about the result tomorrow, from the confidence given to me by the circumstance of having heard in a tent, in the Sahara, the magical goal of Rivaldo that qualified us to play the Champions League” (“Tot el camp és un clam!” in: Op. cit. p. 21).

Following Barça’s matches in his travels: “To give you some idea, I was giving some talks at the University of San Diego, in California, and I wanted to know what Barça had done. Some students who joined the course, through the Internet, managed to tell me what was happening.” (“Barça i integració”. Amb blau sofert i amb grana intens. Cent anys del Barça. Barcelona: Proa, 1999, p. 154).

“On a recent visit to present the Dutch version of Galíndez, I had reserved a sacred space for myself to witness Galatasaray-Barcelona broadcast live on Dutch television.” (“En un momento dado”. El País. 11 December 1993. p. 28).

“I witnessed in Havana that famous match in which Valencia came back from three goals behind Barcelona and when the chés [Valencia] scored the fourth goal, a Spaniard who was next to me, stood up in ecstasy and shouted: Viva España!” (“Naranjas, naranjitos y naranjazos”. El País. 2 May 2000. p. 53).

An international landmark of Barcelona-ism: “A Swiss television crew was travelling around Barcelona filming the city and its literatures and, suddenly, its members came across the events of La Rambla and began to ask questions. What do these kids want, revolution? (…) But they still didn’t understand the flags, the patriotism in whose name the hooliganism could be made. Having to give them a justification I heard myself reciting the old speech about the identification of Catalonia with Barça, and I found my speech unconvincing. (“Nueve días y medio”. El País. 20 May 1989. p. 27).

“In Holland they have asked me for my opinion of Cruyff on the occasion of his 50th anniversary.” (“Post-Cruyffism”. El País. 20 April 1997. p. 48).

A medium with the history of Catalonia: “The team of Barcelona Football Club, of Barça, also acts as a medium. But I dare say that, after the spiritualist contact with victory or defeat, there remains a further contact, so subtle that it remains at the level of foreboding: but certainly evident to anyone who has been in Catalonia not just passing through. The medium establishes contact with nothing more and nothing less than the history of the Catalan people itself.” (Barça! Barça! Barça!”. Triunfo. No. 386. 25 October 1969. p. 25).

From the publication on the cover of the magazine Triomf of Barça, Barça, Barça, endorsements were written to me by monks from Montserrat to aspiring general secretaries of the PSUC and intellectuals in self-exile in Paris, as well as Oriol Bohigas and Salvador Espiru, letters that I received as if they were a lifetime safe-conduct for all the galaxies of Catalan-ness” (“Tot el camp és un clam!”. Avui. 14 June 2003. p. 21).

A badge of identity: “But I believe, I firmly believe, that the significance of Barça beyond sport is loaded with congenital innocence. Peoples need signs of identity, especially those peoples who have lived in permanent risk of losing them, and Barça is above all a sign of identity.” (“El Barça is different”. Tele/eXprés. 8 April 1974. p. 4).

The army of a disarmed country: “Everything that didn’t sit well with the official and absolute truth of Francoism became a fact of objective opposition and the Barcelona football team polarised the nationalist desires of the Catalans, as if it were the unarmed army of a country with its identity crushed by the victor in the civil war.” (Vázquez Montalbán, Manuel. «Barça: el ejército de un país desarmado». Catalònia, 1987, Núm. 1, p. 45)

The symbolic disarmed army of Catalan nationalism:

“Why does Basté de Linyola think he’s interesting?

He’s a politician, a more or less frustrated one. He wanted to put the economy, democracy, Catalonia in order, and now he wants to order the epic sentimentality of this country by returning to the club its character as an unarmed symbolic army of what it means to be Catalan.” (El delantero centro fue asesinado al atardecer. Barcelona: Planeta, 1988, p. 92).

“Mr Robson has used my keen observation that Barça is the army of Catalonia, minimising it, because in fact my cognitive proposal was more complete: it’s the symbolic and unarmed army of Catalonia” (“El sofriment”. Avui. 19 April 1997. p. 20).

A disarmed memory:“Founded by Joan Gamper the Noi del Sucre brought the masses the bosses the designer stand a girl from Torroja would sing to the boy of the moon from Madrid the heart so white …” («Desarmado ejército simbólico de una memoria desarmada». El País. 7 May 1998. p. 43).

International repercussion: “Perhaps the phenomenon is explained by the fact that in those years Catalan nationalism resurfaced in the face of the crisis of the Spanish centralist state, nationalism driven by the development of the Catalan industrial bourgeoisie and crisis of the Spanish state aggravated by the loss of the remains of the Empire. Fútbol Club Barcelona is immediately adopted as the epic expression of the Catalan national renaissance. Catalonia has a language, a culture of its own, a sovereign historical tradition during the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance, a native cuisine but it does not have a state or an army. Something paired with a state is pursued through the autonomic or federalist claim, but there is no other possibility of an army than the eleven pairs of boots of the Barcelona players, “El Barça” according to the apocope that popularises the name of the club” (“El Barcelona F. C.: algo más que un club”, Sport International, September 1987, page numbers unknown).

“Barcelona F. C. is something more than a club’. This phrase was spoken by a president of Barcelona [football club] shortly before Franco died and expressed the opinion of many thousands and thousands of Catalans, convinced that their favourite football club is a national symbol of Catalonia, as the Virgin of Chestokova is a national symbol for the Poles. Indirect symbolic elements flourish under dictatorships because the symbolic elements of identity are usually forbidden. Was Barcelona then “something more than a club?” I think so.” (“El Barcelona F.C.: algo más que un club” Merian, 14 October 1991, page numbers unknown).

“It is already known even in Europe, where until recently they knew nothing about Spain, that Barcelona Football Club, Barça, is more than a club, it is the unarmed symbolic army of what it means to be Catalan.” (“Un drama de la globalización. Los problemas de identidad del Club de Fútbol Barcelona”. La Reppublica, Settimanale. 5 November 1999. No pagination).

Film Barça, Barça, Barça: “The origin of the film can be traced back to that extraordinary report published a year and a half ago by Manolo Vázquez Montalbán in the magazine Triunfo with the same title of “Barça, Barça, Barça” and that had such wide repercussions at the time. Manolo tells us that the idea of filming the film came to Jaume Lorés during the triumphalist era of the League, at a time when Barcelona seemed to be going to win the Championship easily.” ( «Barça, Barça, Barça». Barça. No. 802. 30 March 1971. No pagination).

Book on the history of FC Barcelona: “The work undertaken by a group of outstanding Catalan university students to collect in a book the various aspects of the socio-cultural impact of FC Barcelona constitutes, in all likelihood, an unprecedented research effort in the history of football” (“Los 75 años del Barça en un libro”. Barça. No. 954. 26 February 1974. No pagination).

Film El fantasma del estadio: “Through these lines, I would like to inform you, as President of the Organising Committee of FC Barcelona’s Centenary Events, our sincere support for the project, which you so worthily direct, to make a film about our Club, as well as its inclusion in the Centenary Events Programme. In addition, we also agree that the renowned writer Manuel Vázquez Montalbán should be the person to write the script for this film”. (Letter from Josep Caminal, Vice President of FC Barcelona and President of the Organising Committee of Centenary Events, dated 2 December 1996).

Homage at Camp Nou

“Just a few hours ago, Manolo Vázquez Montalbán announced by phone that he wanted to arrive in time to watch Barça’s game with Depor. He didn’t want to miss it. Unfortunately, he won’t be able to sit up there, in his chair in row 34, in the Second Tier.

For 36 years Manolo, his wife Anna, their son Daniel and a group of friends have sat together to enjoy and also to suffer with the Barça first team game.

Manolo was certainly Barça’s brightest and most lucid chronicler. For many years his articles have spread an image of Barça that has served to neutralise what others wanted to spread about our club. His was a sentimental, ironic but very endearing Barça-ism.

He was the first during the Franco dictatorship to write that Futbol Club Barcelona had become “a sign of identity of the Catalan people” and that it showed it all over Spain, at all costs, whatever happened.

I think today we must all remember that whole-hearted Barcelona fan who was Manolo Vázquez Montalbán”. (Speech by Borja de Riquer in memory of Manuel Vázquez Montalbán at Camp Nou, 2003)

A homage to the writer and his civic values: “In 2004 the Association of Journalists of Catalonia and the Barcelona Football Club Foundation called for the first time the Vázquez Montalbán International Journalism Award, in the category of “sports journalism”. The aim of this award is to pay tribute and remember this great writer and, in turn, stimulate journalistic creation inspired by the civic values that permeate his sporting work and, above all, his life-affirming attitude. The joint initiative of these two entities allows us to keep alive the memory of a figure who made rigour, ethics, commitment, and self-criticism a constant in his professional practice” (FC Barcelona website).

Sports journalism and Barça [Chat about Futbol Club Barcelona. 19840228. 19840228. Programa Las Cenas de la Dorada]]. Radio Barcelona. 10.45 al 13.52.

Awarded

- 2004: Patrick Mignon

- 2005: Joaquim Maria Puyal

- 2006: Juan Villoro

- 2007: Simon Kuper

- 2008: Candido Cannavò

- 2009: Ramon Besa

- 2010: Eduardo Galeano

- 2011: Santiago Segurola

- 2012: Nick Hornby

- 2013: Sergi Pàmies

- 2014: Eduardo Gonçalves de Andrade Tostão

- 2017: Michael Robinson

- 2018: Emanuela Audisio

- 2019: Jorge Valdano

- 2021: Gary Lineker

A bad sports education: “Our bad sentimental education became bad sports education, worse, impossible sports education. Only in schools from the urban waist up did they know what a stopwatch was for and years later, when the educational authorities tried to impose “sport” in neighbourhood schools, located in flats and with no other possible teacher than the principal’s skinniest daughter, the one who did the business was the nearest carpenter, responsible for making a vault, for example, by eye or ear, with the obvious risk that an entire class of schoolchildren like us would lose on their backs the future possibility of a career as Japanese sex athletes”

“Opening your eyes to the sense of muscle in the post-war period was not stimulating. The only sports facilities for the common folk were the vacant plots opened by the bombs, improvised football fields for balls made of rags, tin or rubber and, instead of showers, some hydrants or those fountains of Barcelona” (“Crónica sentimental de la musculature”. in: Olimpiada Cultural, 16 November 1990. No pagination.).

Football on vacant sites on the outskirts of the city: “When we were kids, between Barcelona and l’Hospitalet there were twenty kilometres of vacant sites. In Montjuïc, the Expo exhibition halls that had collapsed were esplanades where we went to play football” (“Barça i integració” in: Amb blau sofert i amb grana intens. Cent anys del Barça. Barcelona: Proa, 1999, p. 152).

Football among paving-stones: “Marcet, a very fine winger who once kicked a ball that someone gave him in a street (you could play football in the streets then), a mate of knock-abouts. Marcet took the ball, passed it from one foot to the other, flipped it to one shoulder, then to the head, dropped it on the tip of one foot… in short, he showed ball control. After the event there was a division of opinions. The most radical wing of the little band gathered there reproached the one who had passed the ball to Marcet for fraternising with the enemy. But, fortunately, the moderate majority prevailed and Marcet, despite being an Español supporter, entered our mental Olympus and during the years that remained of friendship and adolescence we remember that day when Marcet passed through our cobblestone stadium.”(“Enemigos para siempre”. El País, Deportes, 29 November 1992, p. 48).

The Flors de Maig 11-a-side football team: “The Flors de Maig (Mayflowers) team was made up of people who worked with publishers (Planeta, Salvat, Enciclopèdia catalana, Larousse), as well as some young university students. Two teams were set up, I don’t know how, one was the Mayflowers, which was called Atlético Marxista and we were in red, and another was the Real Acrata who were in black and was the team we normally played against. Here there were many diverse people, even a professor who was vice-rector of the University of Barcelona and Enric Fusté, financial advisor to Manolo and who appears in Carvalho, Jordi Borja, Solé Tura, it was a mixture of people from the publishing and the political worlds. We normally played on Saturday or Sunday mornings. I remember a significant anecdote. We went to play in La Verneda, in Poblenou, a working-class neighbourhood, adjacent to the ground of La Bota. We were playing and there was one thing that was striking even though we didn’t lend it any importance was that looking at both teams possibly three-quarters of the players wore beards, because it was a time when long hair was in style, and someone in the crowd said “these teams spend less on barbers than the Russians on catechisms”. It was striking because it wasn’t the run of the mill teams of young people in the neighbourhood, but people from the publishing world, usually left-wingers, who ended up calling and saying we need eleven to play… I remember these matches that were held from time to time, I remember taking part two or three times a year, mostly in the spring.” (testimony of Borja de Riquer).

Futsal team with the colleagues of the CAU magazine

Centre-forward position

MVM: I was a centre-forward because I was a bit heavy, I led the charge…

E.V.-M: Who were you like?

MVM: It was what they called the “Spanish fury”. I was a buffer, but from time to time I scored goals»

(«Barça i integració». aavv. Amb blau sofert i amb grana intens. Cent anys del Barça. Barcelona: Proa, 1999, p. 153)

«I remember that at that time if you wanted to have a place to hold meetings you could only join the Youth Front or the local Catholic Centre. And I signed up for the Catholic Centre of the El Carme parish.

By the way, I often bumped into Benet and Jornet there, and Antoni von Kirchner. They would meet there to play ping-pong.»

(Quim Aranda. «Què pensa Manuel Vázquez Montalbán». Interviwed by Quim Aranda. Barcelona: Dèria Editors, 1995, p. 27)

Physical exercise in the Centro Gimnástico Barcelonés

Poem “Bíceps, tríceps”

“Bíceps, tríceps…

He had died

when attempting to do a handstand

on two lacklustre stools,

drops of lemonade

or indentation, sweaty hands of couples

between one Sunday dance and another

on the outskirts, picnic areas

with yellow papers and purple

garlands

But no one silenced the squeal

of the pulley, nor did it stop spinning

on the fixed bar, not did the vault rear up

at the reckless jumps of artistic

gymnasts

and in front of the mirror, biceps

triceps with rusty weights, deficient

neighbourhood gym equipment

improve the race

expensive project of informative leaflets

biceps and triceps from seven in the morning,

turners, die makers, carpenters

even heirs to grocery stores,

dry cleaners, electrical accessories,

nuts

the son of the local pharmacist raised

the rope with a half-iron unassisted

and in the summer

I made love on the sand with disenchanted Swedish women

white thighs and small breasts

somewhat sad, somewhat rich, somewhat frigid in Sweden,

in Spain dazzled by the sun, Spain

is different and the biceps of stallions

warm as a whispered song – the girl

from Puerto Rico, for whom do you sigh?

They sighed.

rhythmically -breathe in-breathe out-biceps-triceps-

or exchanged obscene words, obscene gestures

with girls somewhat made up, fishnet stockings

and blue, pink, home-knitted cardigan,

They learned cutting and tailoring in the windows

close, uselessly blushing because of an

unforeseen sex peering from the window

between biceps

and triceps, raised curious eyes

towards the terrace

where serious, like vegetarians,

the supporters of Swedish gymnastics,

high school children, round-bellied paterfamilias,

Aspirants and Instructors of Accion

Catolica, men with principles and readings

graduates, Muller, Swedish gymnastics

and Health, rites, one two, one two or ow, or ow,

the teacher raised his hands towards the mist,

on the grey tiles of unwashable green beans,

under the TV aerials, the cry of distant sirens in the port, in the factories

«Las ocho y media de la mañana en la Ciudad Condal». Una educación sentimental. Barcelona: El Bardo, 1967, p. 24-26

Boxing during his childhood: “We all belong to the country of our childhood and I am from the nineteen-forties. There was a young boxer who had won the golden glove before the war and who tried to throw a hard punch to gain the victory that he would never achieve.” (Luis Lopez Doy (dir.). Manuel Vázquez Montalbán: el éxito de un perdedor. Madrid: Televisión Española, 1997). If we can obtain the video, it can be included as an audiovisual resource.

Young Serra: “Another name I think is important is Young Serra, the name of the boxer who appears in El Pianista and is also the main character of the short story “Desde los tejados”, in “Historias de familia”. (…) At that time there was a featherweight boxer in Spain called Young Martín and he was scrawny, like half a kilo of boxer, but he won fights, he was the European featherweight champion.” (Georges Tyras. Geometrías de la memoria. Granada: Zoela, 2003, p. 143-144).

Young Serra’s training in El pianista:

“The other one runs over the burnt bricks, marked by the urine of the dogs that have left behind their shit burnt by the suns that the dancing runner uses as obstacles for the fencing-like tension of his steel legs, like steel cables, Andrés comments mentally when he sees him leap and jump and make movements to pivot and strike his own shadow.

You’re going to make yourself ill if you keep training like this and eating the rations they give us, Young. Stop now, damn it, Young.

But Young, Young Serra, “golden glove” champion of the bantamweights of Barcelona, flits around Andrés and even pretends to hit him, bringing his fist two centimetres from his chin.

“One of these days you’re going to hit me.” (El pianista, p. 87).

The cycling epic: “We love cycling those who since the time of Bernardo Ruiz turned it into an epic cutout on the school desk, and the giants of the route were just that, the giants of the route, without anyone asking them for explanations about gasoline or wood gas, in the case of the Spaniards, who guzzled it down” (“The Tour” El País. 9 June 2001. Last page).

“I wish there were a Tour every month, because I know there are other important stage races, but the Tour is the true religion and since the times of Bernardo Ruiz, Koblet and Kubler, I live a whole year obsessed with the Tour and when I am no longer in this supervisory role one of my sadnesses, if I take any with me, will be not knowing what the Delgado of the day has done in the Tour” (“Pericomania” Interviú. No. 690. 1 August 1989. p. 122).

Football on the radio: “The comeback of Matías Prats is a bit like recovering a childhood. I remember those football broadcasts in which the voice of Matías Prats managed to turn Gonzalo III into Siegfried, Basra into the real monster of Colombes and Gainza into a fox impossible to hunt, even the English abstaining” (“The return of Matías Prats” El Periódico. 30 May 1981. p. 39).

Football on television: “And one has an elephant’s memory, an immense memory in which one keeps the collective celebratory tone of the victory over England in 1950. They were the same faces, the same vented frustrations, the same desire to give meaning to life and history, since it is not given by the daily exercise of living. I watched the 1950 match surrounded by Spaniards who were diverse in their ideology” (“Gol, gol, gol, gol, gol, gol” in: Triunfo. No. 774. 10 December 1977. p. 20).

“I have thought about my most immediate epic horizons and a football league awaits me that I don’t intend to miss. As for TV, I only watch movies and football matches regularly, everything else is a gerund or has an absolute majority.” (“Saviola y Zidane” Interviú. No. 1319. 6 August 2001. p. 106).

Live football: During my long stay in the Americas, I received a privileged invitation: to attend a Boca Juniors match in the presidential box. It is not a box in the European manner, but glazed, a protected window open to the spectacle of this sweetshop located in one of the most working-class and, in a sense, down at heel neighbourhoods of Buenos Aires” (“Boca, algo más que un club” Interviú. No. 1181. 14 December 1998. p. 114).

The feats of Santana: “I like tennis and I like it thanks to television because I belong to the large number of Spaniards who discovered this sport in the sixties, thanks to the television broadcasts of the deeds of the great Santana” (“Tennis and television” El Periódico. 27 November 1982. p. 43).

The pen-name Luis Dávila: “I thought that name [Luis Dávila] reminded me of a sports journalist. At that time no Spanish intellectual was able to talk about sport because that seemed to them a mediocre, minor thing, and to report on sport or do sports criticism it would seem as if the rings fell from his fingers, so I looked for a pseudonym that seemed to me to sound like a sports writer” (Roberta Erba. Los pseudónimos de Vázquez Montalbán, interview held on 6 June 1994).

The duels with Javier Marias: “Whenever a Barcelona-Real Madrid or vice-versa classic came around, they would nearly always drag me and Javier Marias out of our autumn barracks to show our heart so white or so blue and claret” (“Adiós, Barça, adiós”. El País. 13 October 1999. p. 64).

Publications about the Barcelona Olympic Games: “As the Olympic Games grew closer, I received journalists and social theologians from all over the world who sought in me a critical Virgil of the city and the relationship between the city and the games” (“El loro y los Juegos Olímpicos”. Profil. 14 September 1992. No pagination).

Le Monde Diplomatique and football: “The fact that a publication conventionally so serious and so aware of what is necessary news as Le Monde Diplomatique should devote a monographic issue to football just a few months ago shows the importance that this secular godless religion is acquiring, one that is endowed with a rigorous ritutal and worrying ends. In the piece that Le Monde Diplomatique asked me to contribute, I took as my starting point the evidence that Berlusconi would probably never have become prime minister of Italy without the help of the Milan of Van Basten, Gullit and Rijkaard” (“El fútbol, una religión sin Dios”. Interviú. No. 1124. 10 November 1997. p. 122). This article was published in August 1997 with the title “El fútbol: una religión civil en busca de un Dios (football – a civil religion in search of a God”.

L’Équipe and sport: “The newspaper L’Équipe asks a series of politicians and intellectuals to state their views about the meaning of sport at the end of the century, the end of the millennium”. (“L’esport”. Avui. 18 December 1999. p. 19).

“There was Carvalho in front of the cemetery gate, in a silent dialogue with the old glory, a piece of the collage of his childhood when they reproduced it as a slogan of the posters announcing the Sunday matches, hooked behind the windows of the most crowded establishments on the street: the mandatory bakery of mandatory post-war black bread or the dry cleaner’s where the four daughters of Mrs. Remei bloomed. Four breasts in bloom that roamed the street under the rain of lewd whistles, co-owners of flesh unbecoming of a post-war of a general and equally mandatory rationing” (El delantero centro fue asesinado al atardecer. Barcelona: Planeta, 1988, p. 141).

Political and social identification: “In the Raval neighbourhood and in the Barrio Chino, the native Catalan workers and those descended from migrants were mixed together. And to cohabit precisely means to know that there is one who is different, because they talk differently and they have different habits and customs, other symbolic referents that you feed on little by little, such as Barcelona football club, for example.” (Georges Tyras. Geometrías de la memoria. Granada: Zoela, 2003, p. 40-41).

“When at school we commented on the results, I already knew that it was a team that was, let’s say persecuted, because it had been a Catalanist team, the Francoists had executed its president in 1936, and a Barcelona team had gone around the world playing matches and promoting the Republic, just like another from club in Bilbao; Some of those footballers were later exiled. You assimilated all that in a diffuse way and took it on board as a sign of participation in the country” (Georges Tyras. Geometrías de la memoria. Granada: Zoela, 2003, p. 41).

FC Barcelona in his sentimental education and cultural admixture: Poem Visualizaciones sinópticas (end of the poem “Visualizaciones sinópticas”, included in Escritos subnormales).

The songs of his childhood: “In a neighbourhood now called Raval, it even has its own Rambla, and which then was called Chino or disrict V, it was impossible to sing The International or La Varsoviana or Els segadors, songs for Republican times. But we did sing in pure ‘charnego’ [Catalan influenced by Castilian as spoken by economic migrants from other parts of Spain – pejorative]: If a dove comes to your window/treat it kindly because it’s from Barcelona/If a little owl comes to your window/hit it with a stick it’s from Espanyol. Or we would recite: There are six things in this world that shine brighter than the sun / the six cups of Barcelona and the shit of Espanyol (“Kubala, entre Gamper y Cruyff”. El País. 18 May 2002. p. 42).

Kubala: “I was impressed by Kubala, the first wizard of the ball for those of us who had not seen Samitier play” (“Manuel Vázquez Montalbán”. Pere Ferreres. Cien años azulgrana: entrevistas a la sombra del Camp Nou. Madrid: El País-Aguilar, 1998, p. 203).

The Barça of the 5 Cups: “When I got out of that strange club (jail), I went through a period of football non-belief, until I asked myself: which is more stupid, to believe in Basora, César, Kubala, Moreno and Manchón or in Carrillo and el Guti? I decided to believe in Barça and to study very closely the politics that affected me, but always, always, based on the evidence that neither history, nor life, nor Europe were what we deserved” (“Credo”. El País. 21 May 1992. p. 54).

To Les Corts with some family members from the neighbourhood: “I went many times with my relatives to see “Barça” play at the old Les Corts ground. There were seasons when I didn’t miss a match” (“Barça, Barça, Barça”. Barça. No. 802. 30 March 1971. No pagination).

“I used to go to Les Corts [football ground] because a wholesaler who was a part relative of mine had a member’s card. ”I didn’t need it and I generally sneaked into the zone where the crowd pushed en masse” (“Barça i integració”. Amb blau sofert i amb grana intens. Cent anys del Barça. Barcelona: Proa, 1999, p. 156).

To the Camp Nou with a group of friends and his father-in-law’s member’s card: “I stopped going to the stadium for a several years. From 1964 I started going again, and since then I have renewed my father-in-law’s member’s card every year; he has number eight thousand and something. My wife also has a really low member’s number. I still have my father-in-law’s member’s card because he can’t go to the ground any more and he would be very upset if I were to take out a new one, as he is a real “culé” (a diehard Barça fan). I go to the “Camp Nou” with my wife and a group of friends, who are lecturers at the Autonomous University – Sergi Beser, Pep Termes, Jordi Argenté…” (“Barça, Barça, Barça”. Barça. No. 802. 30 March 1971. No pagination).

From the terraces to the President’s box: “When I started going to football, I used to go to the Les Corts ground; now I go to the upper main grandstand and, unlike Mr. Baret, I have completely forgotten those times, because in the grandstand you are much more comfortable and, on the other hand, it is one of the few places in the country where the police treat you with respect” («Vázquez Montalbán, president del Barça?». Oriflama. No. 93. March 1970. p. 25).

The admiration of technical and skilful players: “I’ve burst many a blood vessel for Reixach and for Suárez. The Barça crowd also liked the players with the foreheads tinged red with martyrdom, those who sweated the shirt, and barely appreciated those who have fun playing” (“La esquizofrenia del entrenador”. El País. 22 October 1995. p. 14).

“I’m seasoned by life and football fields and I, who have seen Kubala dribble with his hips, Eulogio Martínez dribble sideways, Di Stefano reinvent the football field with his imagination or disguise himself as a post, Cruyff score goals with his fringe, I regretted the other day never wearing – but never – a hat to take off when I saw Romario leaving Osasuna’s goalkeeper beaten and lonely with a perfect chip”. (“Esplendor en la yerba”. El País. 10 October 1993. p. 44).

“And now I adore De la Peña, who is brilliant and bonkers. I remember one day, Robson was the manager, when Ivan tried a great pass, Robson came off the bench to see it. When he missed, he turned to the bench with his hands on his head to show that he was mad. But Ivan tried it again later and he got it right” (“Barça i integració”. Amb blau sofert i amb grana intens. Cent anys del Barça . Barcelona: Proa, 1999, p. 146).

The post-match discussions in his home in Les Corts: “There were also people in the PSUC who enjoyed football, like Pepe Termes or Fontana, and every time we went to the stadium, after the game we would comment on the plays at home, and I realised that I wasn’t so heterodox. (“Manuel Vázquez Montalbán”. Pere Ferreres. Cien años azulgrana: entrevistas a la sombra del Camp Nou (A hundred years of blue and red: interviews in the shadow of the Camp Nou stadium). Madrid: El País-Aguilar, 1998, p. 203).

“And when the match was over, the meetings we held at home, with Borja de Riquer, Pep Termes, Josep Fontana, Jordi Argenté, and sometimes Jordi Solé Tura, among other centre-forwards. There was a lot of drinking, a lot of arguing, and little was resolved.” (Daniel Vázquez Sallés. “Más que un adoquín”. El País. 1 June 2003. p. 51).

Supporting Barcelona, a secular religion: “However, I have always said that I preferred to be religious in football so as not to have to be religious in love, in politics, or in religion. Each to his own faith. Like Serrat, I believe in Basora, César, Kubala, Moreno and Manchón” (“El Barça és el nostre club”. Ramon Barnils (Ed). Decàleg del culé (The Ten Commandments of the FC Barcelona supporter). Barcelona: Columna, 1992, p. 17).

“Impossible to forget that the celebration of the Centenary of Barcelona FC has begun, an institution that I declare I support for the same reasons that Joan Manuel Serrat does. We are both kids from the block and we became Barça supporters because in the shops in the country when we were boys there were posters depicting how Samitier would dribble past a player, any player, of Español. We both became Barça fans thanks to the deeds of Basra, César, Kubala, Moreno and Manchón. And we still are because Barça was the symbolic army of an idea of what it means to be Catalan that is of the people, secular, with no need to go on a pilgrimage to any mountain other than the terraces of the Camp de les Corts or the Camp Nou” (“El Barça del desencuentro”. El País. 28 November 1998. p. 46).

“We agnostics have to be given a chance to believe in something, and I take it by believing firmly in the revealed truth of Barcelona Football Club.” (“L’esport”. Avui. 18 December 1999. p. 19).

Always with an eye on his team’s results: “And the thing is that, since childhood, an important part of my calendar has been prefixed by national football competitions and the role that my favourite team played in them. I know that the worst thing that can happen to an intellectual is to know which part of his brain has a limp, so it is in football as in politics. There’s nothing we can do about it. My fate was decided long ago” (“La Copa”. El País. 21 June 1985. Last page).

“I confess that I sometimes, when I have thought about death, fretted about the impossibility of knowing how Barça would do in the League. For me, dying meant never again to know who had won the League, and to fear the last critical-biographical comment that Rafael Conte would doubtless dedicate to me in EL PAÍS” (“Volver a empezar”. El País, Deportes. 28 August 1989. p. 12).

Following Barça’s matches on the radio: “The first time that Barça lost the European Cup, I was in prison, doing my anti-Francoist duty, but attentive to the football results that were broadcast on the loudspeakers in the prison yard of the Modelo” (“Credo” in: El País. 21 May 1992. p. 54).

“Whatever happens I will find out about the result tomorrow, from the confidence given to me by the circumstance of having heard in a tent, in the Sahara, the magical goal of Rivaldo that qualified us to play the Champions League” (“Tot el camp és un clam!” in: Op. cit. p. 21).

Following Barça’s matches in his travels: “To give you some idea, I was giving some talks at the University of San Diego, in California, and I wanted to know what Barça had done. Some students who joined the course, through the Internet, managed to tell me what was happening.” (“Barça i integració”. Amb blau sofert i amb grana intens. Cent anys del Barça. Barcelona: Proa, 1999, p. 154).

“On a recent visit to present the Dutch version of Galíndez, I had reserved a sacred space for myself to witness Galatasaray-Barcelona broadcast live on Dutch television.” (“En un momento dado”. El País. 11 December 1993. p. 28).

“I witnessed in Havana that famous match in which Valencia came back from three goals behind Barcelona and when the chés [Valencia] scored the fourth goal, a Spaniard who was next to me, stood up in ecstasy and shouted: Viva España!” (“Naranjas, naranjitos y naranjazos”. El País. 2 May 2000. p. 53).

An international landmark of Barcelona-ism: “A Swiss television crew was travelling around Barcelona filming the city and its literatures and, suddenly, its members came across the events of La Rambla and began to ask questions. What do these kids want, revolution? (…) But they still didn’t understand the flags, the patriotism in whose name the hooliganism could be made. Having to give them a justification I heard myself reciting the old speech about the identification of Catalonia with Barça, and I found my speech unconvincing. (“Nueve días y medio”. El País. 20 May 1989. p. 27).

“In Holland they have asked me for my opinion of Cruyff on the occasion of his 50th anniversary.” (“Post-Cruyffism”. El País. 20 April 1997. p. 48).

A medium with the history of Catalonia: “The team of Barcelona Football Club, of Barça, also acts as a medium. But I dare say that, after the spiritualist contact with victory or defeat, there remains a further contact, so subtle that it remains at the level of foreboding: but certainly evident to anyone who has been in Catalonia not just passing through. The medium establishes contact with nothing more and nothing less than the history of the Catalan people itself.” (Barça! Barça! Barça!”. Triunfo. No. 386. 25 October 1969. p. 25).

From the publication on the cover of the magazine Triomf of Barça, Barça, Barça, endorsements were written to me by monks from Montserrat to aspiring general secretaries of the PSUC and intellectuals in self-exile in Paris, as well as Oriol Bohigas and Salvador Espiru, letters that I received as if they were a lifetime safe-conduct for all the galaxies of Catalan-ness” (“Tot el camp és un clam!”. Avui. 14 June 2003. p. 21).

A badge of identity: “But I believe, I firmly believe, that the significance of Barça beyond sport is loaded with congenital innocence. Peoples need signs of identity, especially those peoples who have lived in permanent risk of losing them, and Barça is above all a sign of identity.” (“El Barça is different”. Tele/eXprés. 8 April 1974. p. 4).

The army of a disarmed country: “Everything that didn’t sit well with the official and absolute truth of Francoism became a fact of objective opposition and the Barcelona football team polarised the nationalist desires of the Catalans, as if it were the unarmed army of a country with its identity crushed by the victor in the civil war.” (Vázquez Montalbán, Manuel. «Barça: el ejército de un país desarmado». Catalònia, 1987, Núm. 1, p. 45)

The symbolic disarmed army of Catalan nationalism:

“Why does Basté de Linyola think he’s interesting?

He’s a politician, a more or less frustrated one. He wanted to put the economy, democracy, Catalonia in order, and now he wants to order the epic sentimentality of this country by returning to the club its character as an unarmed symbolic army of what it means to be Catalan.” (El delantero centro fue asesinado al atardecer. Barcelona: Planeta, 1988, p. 92).

“Mr Robson has used my keen observation that Barça is the army of Catalonia, minimising it, because in fact my cognitive proposal was more complete: it’s the symbolic and unarmed army of Catalonia” (“El sofriment”. Avui. 19 April 1997. p. 20).

A disarmed memory:“Founded by Joan Gamper the Noi del Sucre brought the masses the bosses the designer stand a girl from Torroja would sing to the boy of the moon from Madrid the heart so white …” («Desarmado ejército simbólico de una memoria desarmada». El País. 7 May 1998. p. 43).

International repercussion: “Perhaps the phenomenon is explained by the fact that in those years Catalan nationalism resurfaced in the face of the crisis of the Spanish centralist state, nationalism driven by the development of the Catalan industrial bourgeoisie and crisis of the Spanish state aggravated by the loss of the remains of the Empire. Fútbol Club Barcelona is immediately adopted as the epic expression of the Catalan national renaissance. Catalonia has a language, a culture of its own, a sovereign historical tradition during the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance, a native cuisine but it does not have a state or an army. Something paired with a state is pursued through the autonomic or federalist claim, but there is no other possibility of an army than the eleven pairs of boots of the Barcelona players, “El Barça” according to the apocope that popularises the name of the club” (“El Barcelona F. C.: algo más que un club”, Sport International, September 1987, page numbers unknown).

“Barcelona F. C. is something more than a club’. This phrase was spoken by a president of Barcelona [football club] shortly before Franco died and expressed the opinion of many thousands and thousands of Catalans, convinced that their favourite football club is a national symbol of Catalonia, as the Virgin of Chestokova is a national symbol for the Poles. Indirect symbolic elements flourish under dictatorships because the symbolic elements of identity are usually forbidden. Was Barcelona then “something more than a club?” I think so.” (“El Barcelona F.C.: algo más que un club” Merian, 14 October 1991, page numbers unknown).

“It is already known even in Europe, where until recently they knew nothing about Spain, that Barcelona Football Club, Barça, is more than a club, it is the unarmed symbolic army of what it means to be Catalan.” (“Un drama de la globalización. Los problemas de identidad del Club de Fútbol Barcelona”. La Reppublica, Settimanale. 5 November 1999. No pagination).

Film Barça, Barça, Barça: “The origin of the film can be traced back to that extraordinary report published a year and a half ago by Manolo Vázquez Montalbán in the magazine Triunfo with the same title of “Barça, Barça, Barça” and that had such wide repercussions at the time. Manolo tells us that the idea of filming the film came to Jaume Lorés during the triumphalist era of the League, at a time when Barcelona seemed to be going to win the Championship easily.” ( «Barça, Barça, Barça». Barça. No. 802. 30 March 1971. No pagination).

Book on the history of FC Barcelona: “The work undertaken by a group of outstanding Catalan university students to collect in a book the various aspects of the socio-cultural impact of FC Barcelona constitutes, in all likelihood, an unprecedented research effort in the history of football” (“Los 75 años del Barça en un libro”. Barça. No. 954. 26 February 1974. No pagination).

Film El fantasma del estadio: “Through these lines, I would like to inform you, as President of the Organising Committee of FC Barcelona’s Centenary Events, our sincere support for the project, which you so worthily direct, to make a film about our Club, as well as its inclusion in the Centenary Events Programme. In addition, we also agree that the renowned writer Manuel Vázquez Montalbán should be the person to write the script for this film”. (Letter from Josep Caminal, Vice President of FC Barcelona and President of the Organising Committee of Centenary Events, dated 2 December 1996).

Homage at Camp Nou

“Just a few hours ago, Manolo Vázquez Montalbán announced by phone that he wanted to arrive in time to watch Barça’s game with Depor. He didn’t want to miss it. Unfortunately, he won’t be able to sit up there, in his chair in row 34, in the Second Tier.

For 36 years Manolo, his wife Anna, their son Daniel and a group of friends have sat together to enjoy and also to suffer with the Barça first team game.

Manolo was certainly Barça’s brightest and most lucid chronicler. For many years his articles have spread an image of Barça that has served to neutralise what others wanted to spread about our club. His was a sentimental, ironic but very endearing Barça-ism.

He was the first during the Franco dictatorship to write that Futbol Club Barcelona had become “a sign of identity of the Catalan people” and that it showed it all over Spain, at all costs, whatever happened.

I think today we must all remember that whole-hearted Barcelona fan who was Manolo Vázquez Montalbán”. (Speech by Borja de Riquer in memory of Manuel Vázquez Montalbán at Camp Nou, 2003)

A homage to the writer and his civic values: “In 2004 the Association of Journalists of Catalonia and the Barcelona Football Club Foundation called for the first time the Vázquez Montalbán International Journalism Award, in the category of “sports journalism”. The aim of this award is to pay tribute and remember this great writer and, in turn, stimulate journalistic creation inspired by the civic values that permeate his sporting work and, above all, his life-affirming attitude. The joint initiative of these two entities allows us to keep alive the memory of a figure who made rigour, ethics, commitment, and self-criticism a constant in his professional practice” (FC Barcelona website).

Sports journalism and Barça [Chat about Futbol Club Barcelona. 19840228. 19840228. Programa Las Cenas de la Dorada]]. Radio Barcelona. 10.45 al 13.52.

Awarded

- 2004: Patrick Mignon

- 2005: Joaquim Maria Puyal

- 2006: Juan Villoro

- 2007: Simon Kuper

- 2008: Candido Cannavò

- 2009: Ramon Besa

- 2010: Eduardo Galeano

- 2011: Santiago Segurola

- 2012: Nick Hornby

- 2013: Sergi Pàmies

- 2014: Eduardo Gonçalves de Andrade Tostão

- 2017: Michael Robinson

- 2018: Emanuela Audisio

- 2019: Jorge Valdano

- 2021: Gary Lineker

Contributions

Audiovisuals

Manuel Vázquez Montalbán a Fondo. Interview by Joaquín Soler Serrano. Editrama. 21 October 1979. 27:15-28:13.

“Javier Pérez entrevista a Manuel Vázquez Montalbán” para el vídeo Boxiana de Julián Álvarez, 1988 (1:19 fins al final).

Els mitjans de comunicació i la violència en el futbol. Intervenció en el programa Buenas noches, de Mercedes Milà. RTVE play. 10 de maig de 1984.

El significat polític i social del Barça en democràcia [tertúlia sobre el Futbol Club Barcelona. 19840228. Programa Las Cenas de la Dorada] Radio Barcelona,

Interview with Jorge Valdano, winner of Vázquez Montalbán sports journalism Award. El Periódico. 9 de febrer de 2020. From the beginning to the 48th second.

Sports articles

“Eddy Merckx, en la corte del rey Balduino”. Triunfo, núm. 426, 1 de Agosto de 1970, p. 5.

“Adiós a Santana. Un difícil relevo para al Supermán nacional”. Triunfo, núm. 435, 3 de Octubre de 1970, p. 6.

“Corra, busque y llegue Vd. Primero”. Triunfo, núm. 456, 27 de Febrero de 1971, p. 46.

“La caida del Clay Power”. Triunfo, núm. 459, 20 de Marzo de 1971, p. 6.

“Los intelectuales ante el deporte”. Pròleg a Política y deporte

“El 98 del deporte español”. Triunfo, núm. 476, 13 de Noviembre de 1971, p. 50.

“Los Kubala Boys”. Triunfo, núm. 459, 20 de Marzo de 1971, p. 26

“César Pérez de Tudela: el alpinista del desarrollo”. Triunfo, núm. 477,20 de Noviembre de 1971, p. 1

Sport on television

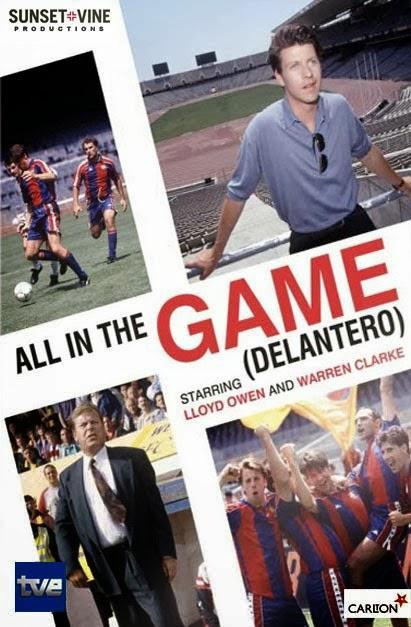

Series “Delantero” TVE (script by Vázquez Montalbán based on the career of Gary Lineker in FC Barcelona). 1993

Young Serra peso pluma. Las aventuras de Pepe Carvalho. Script by Vázquez Montalbán. 1986.

Olímpicament mort (film produced by TV3 1986 based on a novel by Vázquez Montalbán, in which he also takes part as narrator).

El delantero centro fue asesinado al atardecer (episode of the series “Pepe Carvalho”, Tele 5 1999). Available at the Biblioteca de Catalunya.