Politics

Text and selection of content: José María Izquierdo

Critical intellectual

The works of Manuel Vázquez Montalbán are shot through by his political and ethical ideas. The themes of the role of the critical intellectual, his search for the subject of change or the notion of democracy are central in his essays and literary works. In this section I wanted to show a series of general quotes in which his axiom of changing history and changing life is manifested. It does not seem productive to repeat his ironic descriptions of Sacristan, Guerra, González, Carrillo, and so many other figures of recent Spanish history.

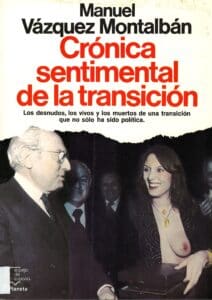

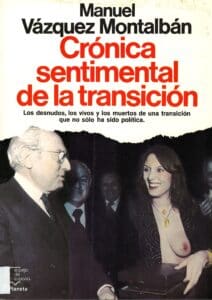

With Felipe González

With Josep Tarradellas, Juan Benet, Anna Sallés and Rosa Reyes, in exile.

Selection of texts

and change Life and History, nonsense not even alerted by the tarnished image that Rimbaud and Marx already had by then. Peter Weiss

had put down in writing the unhappy ending of the testament of modernity. Marat embraced to the point of asphyxia the theological ghost of collective revolution and Sade turned the famous individual revolution into a filthy collection of back numbers of El Caso. But we were still young, no doubt younger than we are now, and we speculated in the alcove-catacombs or in the catacomb-alcoves on the sexual revolution and the sex

of the revolution, disdainful, although crushed by El Caudillo, who like a stone commander-in-chief witnessed our gasps from his corner

an active, who could catch us in his organic nets as soon as our gasps diverged too far from the fundamental of any movement.” (Crónica sentimental de la Transición. Barcelona: Planeta, 2010, p. 11).

“It’s hard to explain to you why there was so little reaction in Spain to the legal murder of Puig Antich, a young anarchist who killed a policeman while they were grappling over a gun. Nor was there any reaction from the opposition. The opposition was starting to see the light at the end of the tunnel, with its coffin leading the way, excellency, and didn’t want to risk territories of liberty that had been de facto recovered, for the death of an anarchist. We weren’t even fazed by the savage decision also to kill a poor stateless Polish fellow, whose death sentence had been put off and which was carried out alongside Puig Antich as a second-rate companion that detracted from the political operation. There were some demonstrations, above all in Barcelona. Extreme left. Christians for socialism. Simply horrified at the killing, but the general staffs of the parties tried to detach themselves from violence, in search of a respectability willing to strike a deal for the future arrival of democracy in Spain. That does not mean that we did not swallow that corpse like a bitter pill and that a lot of verbiage was not necessary to make it digestible. Marcelino Camacho, the leader of Comisiones, upon learning of the brutal sentences against those of the 1001 trial, indirect revenge for the murder of Carrero [Blanco], had declared:

“Our convictions are the price for tomorrow’s freedoms.” Someone beside me paraphrased that: “The execution of that lad by the garrote is proof of the weakness of Franco-ism.” And of ours, I thought. But I probably didn’t say it.” (Autobiografía del general Franco. Barcelona, Planeta, 1992, p. 620-621)

“As Lewis Carroll said, words have owners, and the word ‘communism’ has been appropriated by Stalinism…” (Padura Fuentes, Leonardo, “Reivindicación de la memoria. Interview with Manuel Vázquez Montalbán”, Quimera 106-7, 1991, p. 48)

“Dissidence is a critical mirror and perhaps the Cuban leaders should take a break from reading Gramma [the official newspaper of the Cuban regime] to re-read Alice in Wonderland.” («Disidentes», El País, 1 March 1999)

“Agnes Heller, a disciple of Lukács, is the first intellectual living in Eastern Europe who, perhaps inspired by the works of Henri Lefebvre in the same direction, tackles the issue of the role of daily life in relation to role of history, linked to life and history through the same personal subject. Lefebvre’s concern, like that of Heller, is generalised in the Marxist culture at the end of the nineteen-sixties, when new cohorts, in view of the historical spectacle provided by what they brought with them from the 20th century, planned the dual challenge of changing History as called for by Marx and changing Life as called for by Rimbaud. Lukács, in the prologue to the work of his disciple, Sociology and Daily Life, advocates breaking down the barrier that moral rigourism, from Kant to the Marxiologues, had set up between ethical activity and daily life and go so far as to connote the specific social being, for so long reduced to a historified abstraction. Manuel Sacristán, in his prologue to Historia and everyday life, also by Heller, stresses that the author’s preoccupation with the everyday comes as a consequence of the disillusionment that, after the collapse of fascism, a new Europe of the left did not appear, and quotes Thomas Mann when he refers to the exhaustion of the “morally good epoch” in which the collective struggle against nazi dehumanisation gave men [sic] the sense of the community, historical objectives and moral support, in line with the irony that some years later I myself would construct of the disenchantment of the anti-Francoists, with Franco now dead: “Contra Franco vivíamos mejor”.” (Pasionaria y los siete enanitos. Barcelona, Planeta, 1995, p. 352-353)

“…Tete Montoliu on the piano, white jazz for a blind man; Jaime Gil de Biedma talking about Jorge Guillén or Harper’s Bazaar, the Pijoaparte groping a specialist in Pijos Aparte and the piano toying with the evidence that neither today nor even tonight, will be the eighth day of the week.” (‘Jazz blanco y negro’ (Black and white jazz). i, 25 August 1997)

“I would like to know how to write like Vargas Vila or Fernández Flórez or Blasco Ibáñez to tell all this, because nobody will ever tell it and these people will die when their time comes to die, I don’t know if you may ever have thought about it. To know how to express oneself, to know how to put down on paper what you think and feel is like being able to send messages in a bottle to posterity. Each neighbourhood should have at least one poet and one chronicler so that many years from now, in some special museums, people will be able to relive through memory.” (El pianista. Barcelona: Seix Barral, 1985, p. 138-139)

“It’s as if, now, some simians who survived human civilisation would be afraid to remember a dangerous ancestor who dared the excessive gods excessively and through Reason created more monsters than archangels. I take the metaphor, and I stand by it, from one of the best examples of the cinema of science-fiction. Planet of the Apes and Return to the Planet of the Apes]…” (Panfleto desde el planeta de los simios. Barcelona: Crítica, 1995, p. 10)

“…Realising that nor had that been the eighth, the long-awaited eighth day of the week.” (Memoria y deseo: obra poética (1963-1990). Barcelona: Grijalbo, 1996, p. 59)

“…Perhaps the weekdays are right and seven is a useless prolongation of eight, of the never-found eighth day of the week.” (Ciudad. Madrid: Visor, 1997, p. 42)

“As long as the division of labour exists, the function of intellectuals is to act as an external consciousness of the established social consciousness, in order to foster the conditions that can convert the need for transformation into mass culture and, therefore, into a critical consciousness. Only in this way will critical consciousness become historical energy of change.” (Panfleto desde el planeta de los simios. Barcelona: Grijalbo-Crítica, 1995, p. 40)

“There are no unique truths, not final struggles, but it is still possible to find our way by means of the possible truths against the evident non-truths and struggle against them. One can see part of the truth and not recognise it. But it is impossible to see evil and not recognise it.” (Panfleto desde el planeta de los simios. Barcelona: Critica, 1995, p. 145]

“I’m a pessimist, an historical pessimist, and I think that this should be sorted out with a revolution, a revolution that by the way is impossible until 2017. (…) Not like the last one, of course, but it has to be done. (…) Perhaps I screwed up just like October 1917 got screwed up a few months later, but there is so much injustice, so much suffering and so much arrogance on the part of the system’s men in suits, [..] I perform an analysis of an ironic left-winger.” (Un polaco en la corte del rey Juan Carlos. Madrid: Alfaguara, 1996, p. 178]

“The neo-liberal cultural offensive in the last 15 years goes against historical memory and utopia. For liberalism, rooting out memory means leaving history without guilty parties, without causes. And by eliminating utopia it leaves the present and the ways things are predetermined as the only option.” (”Marcos, el mestizaje que viene”. El País, 22 February 1999)

and change Life and History, nonsense not even alerted by the tarnished image that Rimbaud and Marx already had by then. Peter Weiss

had put down in writing the unhappy ending of the testament of modernity. Marat embraced to the point of asphyxia the theological ghost of collective revolution and Sade turned the famous individual revolution into a filthy collection of back numbers of El Caso. But we were still young, no doubt younger than we are now, and we speculated in the alcove-catacombs or in the catacomb-alcoves on the sexual revolution and the sex

of the revolution, disdainful, although crushed by El Caudillo, who like a stone commander-in-chief witnessed our gasps from his corner

an active, who could catch us in his organic nets as soon as our gasps diverged too far from the fundamental of any movement.” (Crónica sentimental de la Transición. Barcelona: Planeta, 2010, p. 11).

“It’s hard to explain to you why there was so little reaction in Spain to the legal murder of Puig Antich, a young anarchist who killed a policeman while they were grappling over a gun. Nor was there any reaction from the opposition. The opposition was starting to see the light at the end of the tunnel, with its coffin leading the way, excellency, and didn’t want to risk territories of liberty that had been de facto recovered, for the death of an anarchist. We weren’t even fazed by the savage decision also to kill a poor stateless Polish fellow, whose death sentence had been put off and which was carried out alongside Puig Antich as a second-rate companion that detracted from the political operation. There were some demonstrations, above all in Barcelona. Extreme left. Christians for socialism. Simply horrified at the killing, but the general staffs of the parties tried to detach themselves from violence, in search of a respectability willing to strike a deal for the future arrival of democracy in Spain. That does not mean that we did not swallow that corpse like a bitter pill and that a lot of verbiage was not necessary to make it digestible. Marcelino Camacho, the leader of Comisiones, upon learning of the brutal sentences against those of the 1001 trial, indirect revenge for the murder of Carrero [Blanco], had declared:

“Our convictions are the price for tomorrow’s freedoms.” Someone beside me paraphrased that: “The execution of that lad by the garrote is proof of the weakness of Franco-ism.” And of ours, I thought. But I probably didn’t say it.” (Autobiografía del general Franco. Barcelona, Planeta, 1992, p. 620-621)

“As Lewis Carroll said, words have owners, and the word ‘communism’ has been appropriated by Stalinism…” (Padura Fuentes, Leonardo, “Reivindicación de la memoria. Interview with Manuel Vázquez Montalbán”, Quimera 106-7, 1991, p. 48)

“Dissidence is a critical mirror and perhaps the Cuban leaders should take a break from reading Gramma [the official newspaper of the Cuban regime] to re-read Alice in Wonderland.” («Disidentes», El País, 1 March 1999)

“Agnes Heller, a disciple of Lukács, is the first intellectual living in Eastern Europe who, perhaps inspired by the works of Henri Lefebvre in the same direction, tackles the issue of the role of daily life in relation to role of history, linked to life and history through the same personal subject. Lefebvre’s concern, like that of Heller, is generalised in the Marxist culture at the end of the nineteen-sixties, when new cohorts, in view of the historical spectacle provided by what they brought with them from the 20th century, planned the dual challenge of changing History as called for by Marx and changing Life as called for by Rimbaud. Lukács, in the prologue to the work of his disciple, Sociology and Daily Life, advocates breaking down the barrier that moral rigourism, from Kant to the Marxiologues, had set up between ethical activity and daily life and go so far as to connote the specific social being, for so long reduced to a historified abstraction. Manuel Sacristán, in his prologue to Historia and everyday life, also by Heller, stresses that the author’s preoccupation with the everyday comes as a consequence of the disillusionment that, after the collapse of fascism, a new Europe of the left did not appear, and quotes Thomas Mann when he refers to the exhaustion of the “morally good epoch” in which the collective struggle against nazi dehumanisation gave men [sic] the sense of the community, historical objectives and moral support, in line with the irony that some years later I myself would construct of the disenchantment of the anti-Francoists, with Franco now dead: “Contra Franco vivíamos mejor”.” (Pasionaria y los siete enanitos. Barcelona, Planeta, 1995, p. 352-353)

“…Tete Montoliu on the piano, white jazz for a blind man; Jaime Gil de Biedma talking about Jorge Guillén or Harper’s Bazaar, the Pijoaparte groping a specialist in Pijos Aparte and the piano toying with the evidence that neither today nor even tonight, will be the eighth day of the week.” (‘Jazz blanco y negro’ (Black and white jazz). i, 25 August 1997)

“I would like to know how to write like Vargas Vila or Fernández Flórez or Blasco Ibáñez to tell all this, because nobody will ever tell it and these people will die when their time comes to die, I don’t know if you may ever have thought about it. To know how to express oneself, to know how to put down on paper what you think and feel is like being able to send messages in a bottle to posterity. Each neighbourhood should have at least one poet and one chronicler so that many years from now, in some special museums, people will be able to relive through memory.” (El pianista. Barcelona: Seix Barral, 1985, p. 138-139)

“It’s as if, now, some simians who survived human civilisation would be afraid to remember a dangerous ancestor who dared the excessive gods excessively and through Reason created more monsters than archangels. I take the metaphor, and I stand by it, from one of the best examples of the cinema of science-fiction. Planet of the Apes and Return to the Planet of the Apes]…” (Panfleto desde el planeta de los simios. Barcelona: Crítica, 1995, p. 10)

“…Realising that nor had that been the eighth, the long-awaited eighth day of the week.” (Memoria y deseo: obra poética (1963-1990). Barcelona: Grijalbo, 1996, p. 59)

“…Perhaps the weekdays are right and seven is a useless prolongation of eight, of the never-found eighth day of the week.” (Ciudad. Madrid: Visor, 1997, p. 42)

“As long as the division of labour exists, the function of intellectuals is to act as an external consciousness of the established social consciousness, in order to foster the conditions that can convert the need for transformation into mass culture and, therefore, into a critical consciousness. Only in this way will critical consciousness become historical energy of change.” (Panfleto desde el planeta de los simios. Barcelona: Grijalbo-Crítica, 1995, p. 40)

“There are no unique truths, not final struggles, but it is still possible to find our way by means of the possible truths against the evident non-truths and struggle against them. One can see part of the truth and not recognise it. But it is impossible to see evil and not recognise it.” (Panfleto desde el planeta de los simios. Barcelona: Critica, 1995, p. 145]

“I’m a pessimist, an historical pessimist, and I think that this should be sorted out with a revolution, a revolution that by the way is impossible until 2017. (…) Not like the last one, of course, but it has to be done. (…) Perhaps I screwed up just like October 1917 got screwed up a few months later, but there is so much injustice, so much suffering and so much arrogance on the part of the system’s men in suits, [..] I perform an analysis of an ironic left-winger.” (Un polaco en la corte del rey Juan Carlos. Madrid: Alfaguara, 1996, p. 178]

“The neo-liberal cultural offensive in the last 15 years goes against historical memory and utopia. For liberalism, rooting out memory means leaving history without guilty parties, without causes. And by eliminating utopia it leaves the present and the ways things are predetermined as the only option.” (”Marcos, el mestizaje que viene”. El País, 22 February 1999)

Contributions

Audiovisuals

Commitment and poetry: “Inútil escrutar tan alto cielo” in a version sung by Loquillo”