BARCELONA

Text and selection of content: Mari Paz Balibrea

Barcelona is the main setting of the works and life of Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, the place where he was born and always lived and the nerve centre of his creative imagination, intellectual life and sentimental education. His creative work and essays contribute to an urban history of the experience and cultural and ethical history of the Barcelona classes without History, from where he sprang, bound up mainly with his birthplace in the Barrio Chino (its red-light district). From the turn of the [20th] century until the Second Republic, this area of Barcelona is a key actor in his works in the development of the vanguards, the class struggle and the possibility of living with fewer inhibitions. When this possibility disappeared at the end of the Civil War, and during the harshest phase of a Franco regime that could only be resisted symbolically, that miserable Barcelona became a refuge for the dignity of those on the losing side.

Very critical of the Transition and the first socialist governments, it is in Barcelona where the author most rigorously and systematically pursued the betrayals and disappointments of a hegemony that advocated forgetting the past as essential and neo-liberal capitalism as desirable.

The transformations in its Barrio Chino red-light district and the 1992 Olympic Games take pride of place. The economics of these transformations met with one of Vázquez Montalbán’s sharpest materialist critiques.

His essays, journalistic and literary works are an essential contribution to the social, cultural, political and sentimental history of the city in the twentieth century. Therefore, as a citizen, Vázquez Montalbán’s presence in the streets and his participation in the civic life of Barcelona were constant throughout his life. The esteem in which he was held by the city’s inhabitants gives us the measure the reaction to his unexpected death. Today they remember him with his name in the metropolitan area of Barcelona; a square, a civic centre, and a high school, are named after him, in addition to the crime novel prize Pepe Carvalho, the protagonist of his detective series

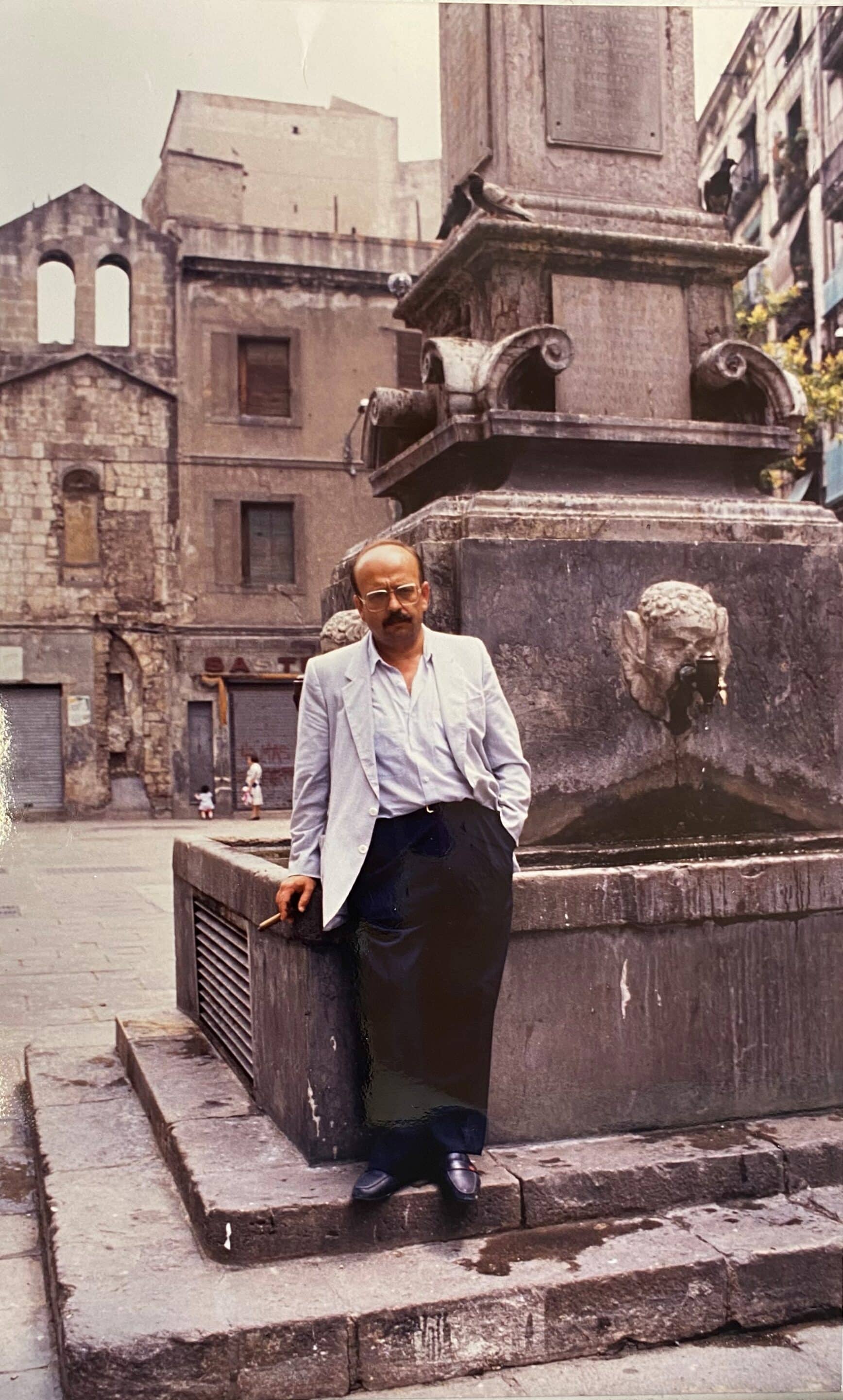

A la Plaça del Pedró de Barcelona, entre 1980 i 1990 aprox. Foto: Guillermina Puig

Institut Manuel Vazquez Montalbán

Plaça Manuel Vazquez Montalbán

Selection of texts

A variegated territory of clandestinity and marginality, where the affective, artistic and political expressions repressed by the bien-pensant and bourgeois Barcelona coexist, we find their traces scattered throughout Montalban’s work, from essays to narrative and musicals

“At the Apolo or the Arnau, on Paral·lel, what is now being called the “frivolous genre” triumphed, with legendary canzontistas, vocalists, such as Bella Chelito, Bella Dorita or Raquel Meyer, muse of the erotic dreams of generations of Barcelonians.” (Barcelonas, Barcelona: Ayuntamiento de Barcelona, 2018, p.183)

“The name [Chinatown] also makes sense as an extension of the concept of a forbidden neighbourhood, because of its status as a territory for the underworld and the lumpen. Barcelona’s Chinatown invaded Escudillers street and its surroundings, like a criminal brand, but its heart was and is on the other side of the Rambla, between Drassanes, Paral·lel and Hospital street. There, whores and working-class families, queer employees and union members of the newborn socialist and communist formations, women’s prisons and Basque gables, condom shops and furniture smelling of disinfectant and English, beach bars selling fine and generous wines with cazalla or barrecha (cazada and muscatel), one of the first cultural syntheses of the connection between the Catalan people and the emigrants, all mixed together.” (Barcelonas, Barcelona: Ayuntamiento de Barcelona, 2018, p. 188)

“This is the Church of Carmen. It was built after the Tragic Week, on the site of a former Hieronymite convent that was burnt down by the revolutionaries. (El pianista, Barcelona: Seix Barral, 1985, p. 33)

“Scene VIII

Panorama of the Paral·lel in the 1920s. Reynals, Patrick and Arrufat come into view in black tie, top hats, etc. They are quite drunk.

Patrick:

I’m confused

In awe,

Horrified,

Overcome,

Splitting my sides,

Blown away,

I’m just

In love with

This city.

On the same day, in the

Same place,

I met

A drunk dictator

Who didn’t dictate a thing.

An Andalusian who’s a

A mad painter

From the Empordà

Who, right in front of me,

Masturbated

Into an envelope

And sent

The results

To his father

Saying: I don’t owe you

A thing.”

(Flor de nit / text Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, sobre una idea de Dagoll Dagom; música Albert Guinovart. Alicante : Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes, 2000, p. 60-62.https://www.cervantesvirtual.com/obra/flor-de-nit-multimedia–0/)

“Scene XII

Quimet’s attic […]

Pons:

Are you guys

Really anarchists?

Or are you regional

Nationalists?

Our final

Struggle

Must be

International

For the victory of the

Proletariat!

Quimet, Pons:

No more kings,

And we still have a king.

Isadora:

And no more clients,

And we still have clients.

No more gods…

Revolution!”

(Flor de nit / text Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, sobre una idea de Dagoll Dagom; música Albert Guinovart. Alicante: Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes, 2000, p. 60-62. https://www.cervantesvirtual.com/obra/flor-de-nit-multimedia–0/)

The author’s assessment of Franco’s entry into Barcelona and its effects leaves no room for doubt:

“Repression was fierce, relentless, merciless.” (Barcelonas. Barcelona: Ajuntament de Barcelona, 2018, p. 243)

“The mood against this background went through ideological neighbourhoods, although it increasingly translated into economic situations: the established Barcelona, with the exception of the culturally nationalist areas, became Francoist to a greater or lesser degree; the other Barcelona ate its own memory or adapted its metabolism to the ingestion of toads and stood firm at dusk, when the flag was lowered in the barracks, profusely scattered around the city, and woe betide anyone who did not stand firm with arms raised at the sound of silence! Once again there was a dual consciousness […]: the city that survived and pretended not to be aware of the shots being fired, of the queues outside the Modelo [prison], of the systematic destruction of its own identity.” (Barcelonas. Barcelona: Ajuntament de Barcelona, 2018, p. 249)

His poems delved into the expression of the experience of that “other” losing Barcelona:

“O city of terror

among the livid avenues

autumn trees

the invaders

shot records

drunk with barbaric memory

fed up with flesh humiliated

and offended

fear was a presence

silence its shroud

words hidden in things

ideas in the eyes

contemplated

the division between the one who dies and the one who kills” (Praga. Barcelona: Lumen, 1982, p. 15)

“Definitely nothing left of April

the cruellest month, poor Rosa de Abril

drawn with death – hypothesis of death –

between my hands your cold face confirmed

the silence to which you bring my memory

the memory of my childhood and your post-war

your youth assaulted by the dogs of History

my youth assaulted by your instinct of life

red Rosa […] ” (Pero el viajero que huye. Madrid: Visor, 1991, p. 59)

Symbolic resistance and solidarity remain to counter the terror and misery in these defeated neighbourhoods:

“Get out of this shitty country and start thriving. […] Either you go or you burst. Sometimes I look over to that side, the one that points towards Calle de la Cera and the Padró cinema, and I imagine I’m up here with a machine gun and all the fascists in Spain pass through that street and ratatatatatata, I don’t leave a single one and it feels good to let off steam. If you ever see me get up there and machine-gun with my mouth, don’t pay me any attention. I’m letting off steam.” (El pianista, Barcelona: Seix Barral, 1985, p. 107)

“The boy circles around a sleeping dog that from time to time opens one eye to watch the bicycle’s intentions.

—Here on the roof he enjoys himself and frees himself from all the shit that the nuns put in his head. My brother-in-law has balls. Red for life. Prison. And he goes and puts my little boy in a school run by the nuns of San Vicente de Paúl, by the Savings Bank, because it’s free, and for the time being, for what they teach him… Well, they teach him to pray. And do you know what book they’ve given him to read at home? Fabiola. A book about martyrs, priests and Romans. I ask Young who Fabiola is, baby.

—A bad whore.” (El pianista, Barcelona: Seix Barral, 1985, p. 109)

“The other day a poor woman came in, full of shit, pardon me, she was carrying a child and asked for something to eat. Without opening the door, I told her through the peep hole to go to the stairs and wait. I saw them sitting on the stairs and I opened the door a little, just enough to put a plate of rice on the floor with a spoon. I closed the door again and through the peep hole I saw them eating it. They left the plate and spoon in the same place and when I was sure they had gone, I went out and retrieved the plate. It was a case of need and they were very hungry, very hungry to eat that rice, because it had been in the cooler for several days and it smelled a bit. It had turned out really good.” (El pianista, Barcelona: Seix Barral, 1985, p. 117-118)

“I told you that the bookseller in Atarazanas was beginning to trust me. Then he told me that, first of all, he always puts the clients in isolation, lest they become police accomplices. The other day, an old bookseller in Hospital Street was caught with Blasco Ibáñez’s La araña negra and Nietzsche’s Así hablaba Zarathustra and was taken to [the police station on] Vía Layetana.” (El pianista, Barcelona: Seix Barral, 1985, p.125)

Vázquez Montalbán was also extremely critical of the great urban transformations in Barcelona which, with Franco’s developmentalism, changed its appearance in the 50s under the leadership of Mayor José María de Porcioles:

“Porciolism set loose the fervour of growth. It led to an empire of repressive urbanism based on the city as a place for transit (the faster the better), as a basis for a construction industry that was attractive enough for the development of an urban capitalism. This all led to the destruction of a city made of pleasant spots, a city that was a place to be, to stroll, to interact with others, etc. Porciolism is the maximum representation of a repressive urbanism of anti-communication. […] After the Spanish Civil War, what Oriol Bohigas calls ‘black market architecture’ found its fundamental political element in Mr Porcioles, and particularly in Porciolism as an urban philosophy.” (Diàlegs a Barcelona. Manuel Vázquez Montalbán y Jaume Fuster. Barcelona: Ajuntament de Barcelona, 1985, p. 54-56)

“…All of a sudden, in the late 1950s and early 1960, it [Cornellà, Santa Coloma, Sant Vicenç dels Horts] was all invaded by horrible blocks of buildings. Of course people needed a place to live, but according to what criteria? Savage criteria. The people who went there to live paid a huge price in their way of life, with psychological, social and personal problems of all sorts.” (Barcelona, cap a on vas? Diàlegs per a una altra Barcelona. Eduard Moreno i Manuel Vázquez Montalbán. Barcelona: Llibres de l’Índex, 1991, p. 85-86)

“…the Barcelona of Porcioles, that vast impersonal car park.” (Barcelonas, Barcelona: Ayuntamiento de Barcelona, 2018, p. 350)

Vázquez Montalbán confirmed that the anti-Francoist work of the Asociaciones de Vecinos (Neighbourhood Associations) was fundamental against porciolismo:

“Barcelona […] already had a critical, political and ideological brew that was quite strong in the 1960s. And what was its outlet? The neighbourhood associations. […] This was one of the most important cultural phenomena in all of Spain: the appearance of an urban critique in the Barcelona of the late 1960s and early 1970s tied to these movements.” (Barcelona, cap a on vas? Diàlegs per a una altra Barcelona. Eduard Moreno i Manuel Vázquez Montalbán. Barcelona: Llibres de l’Índex, 1991, p. 42)

A central element of Montalban’s vision of this period is his critique of how the politicians who led the transition from dictatorship to democracy agreed to grant impunity for the crimes of Francoism and to limit the much more ambitious demands of the anti-Franco left to a framework of liberal capitalist democracy. There are frequent characters within the pages of his work who are political actors with a left-wing past that had a change of heart or went back to their parents’ house.

“—It’s funny. At almost every table a familiar face. The generation in power: between thirty-five and forty-five years old. Those who knew how to stop being Francoists in time and those who knew how to be anti-Francoists in the right measure or at the right time.” (El pianista, Barcelona: Seix Barral, 1985, p. 57)

“[…] we created a fight that we didn’t make. Francoism lasted as long as it had to last, and it overrode what we called our fight.

—But at least we helped to raise democratic awareness.

—As well as Opus initiating the Stabilisation Plan in nineteen fifty-seven and then Economic Development.

—And banning Last Tango in Paris.

—But allowing the bourgeoisie to queue up in cars all the way to Perpignan to see Marlon Brando’s bottom. It was a perfectly assumed dual attitude. Instead, we went forward with the battering ram to demolish the Bastille fortress and we didn’t demolish anything.

—Delapierre, you who are an actor, lecture Joan not to be so revisionist. Revisionists block my brain.

—Joan isn’t a revisionist. She has simply grown up.[…]

—There is a time to make a mistake and time to discover the reason why. But I don’t regret anything I’ve done.” (El pianista, Barcelona: Seix Barral, 1985, p. 56)

“—And you, what?

—Me? What about?

—Politically, boy. I offer an explanation of the correlation of forces present. Joan and Mercè belong to the civilised right, while Delapierre is an activist and a member of the Frente de Liberación Gai (Gay Liberation Front). […] Ventura, your old rival in the conquest of power within the PSUC (Unified Socialist Party of Catalonia), the EBU (European Broadcasting Union), the PCI, Red Flag and again the PSUC, that is to say, wherever we have been, the combative and brilliant old Ventura has become… sceptical… […] And Luisa is a left-wing nationalist and a feminist […]

—And you, Schubert?

—I hesitate between playing along with the socialists to make a run for it and being able to save for my old age, or retiring to my ideological possessions of the past and waiting for better times. —And you? […]

For you, they have changed the song, master. You belong to the fugitives of Marxist knowledge, to the troop that lends language and information to international capitalism, language, information and logic of the enemy and also the satisfaction of having recovered you, master.” (El pianista, Barcelona: Seix Barral, 1985, p. 65, 67-68)

Although Vázquez Montalbán’s criticism is Spanish in scope, it is often embodied in characters from Barcelona, as in the cases cited above from El pianista. Thus, this criticism is very well articulated with the city in his work, thanks to the author’s extensive knowledge of the socio-economic and urban realities of Barcelona:

“I should acknowledge that there have been some programs aimed at recuperating free space within the city, particularly in the most densely populated areas. The opening of the city towards the sea through the Moll de la Fusta and other initiatives represent a certain attempt to recover public space. I’ve also noticed an effort to restore neighbourhood culture, neighbourhood identity. This was a very positive achievement of democracy. However, we are part of a market, and speculation cannot be fought within this framework. The city may have a more advanced, democratic policy of urban culture, but it’s set within the framework of the free market. As a result, developers have the law on their side.” (Diàlegs a Barcelona. Manuel Vázquez Montalbán y Jaume Fuster. Barcelona: Ajuntament de Barcelona, 1985, p. 56)

“The installation of socialists in municipal power allowed many intellectuals and critical professionals from the previous period to stop thinking about the city in order to make it, to enter the temple of actual management, and the impact between reality and desire forced a pragmatic synthesis, favoured – and induced – by dismantling the critical conscience represented by the neighbourhood movement.” (Barcelonas, Barcelona: Ayuntamiento de Barcelona, 2018, p. 334-335)

“What worries me at the end of this theoretical trip (on their part, more ideological than theoretical) is alienation. In other words, I think that at the moment they believe what they’re saying because they need to believe in it. If not, they would have to undergo such a harsh process of self-criticism that it would put a great many things in question. Therefore, they would rather say that there were no other options. And since there’s no way to demonstrate it, this is the problem with the opposition between pragmatic individuals and those who are accused of being utopian. Pragmatic individuals can say: “We did this”, but utopian individuals have to say: “Go look at the newspaper archives to see what we said at the time.” That’s a constant failure. Now nobody will ever think about what that city could have been like. Nobody will be able to consider it, because, of course, it’s an unequal struggle between pragmatic individuals and critical individuals.” (Barcelona, cap a on vas? Diàlegs per a una altra Barcelona. Eduard Moreno i Manuel Vázquez Montalbán. Barcelona: Llibres de l’Índex, 1991, p. 66)

“I’m quite concerned about the hugs Maragall and Pujol give Porcioles […], accepting the systematic destruction of the city that Porciolism represented. […] I’d like to know whether those hugs represent a shared philosophy or a shared vision for the city: the Great Barcelona.” (Diàlegs a Barcelona. Manuel Vázquez Montalbán y Jaume Fuster. Barcelona: Ajuntament de Barcelona, 1985, p. 54)

Vázquez Montalbán said that his homeland was his childhood, the space-time of a poor Barcelona neighbourhood of losers in the first post-war period. References to it run through his bibliography, marked by nostalgia, a tone of vindictive tribute and criticism of an urbanism that despises the imprint of the past in the city.

“There was even a custom –I remember this from my childhood, since I lived in the 5th district– where strolling on Sundays meant walking up and down the Rondes, the Paral·lel and the Rambla. We never left this circuit, because beyond it stood the Eixample, another territory that belonged to another social sector.” (Barcelona, cap a on vas? Diàlegs per a una altra Barcelona. Eduard Moreno i Manuel Vázquez Montalbán. Barcelona: Llibres de l’Índex, 1991, p. 15-16)

“The boiling citizen of the Rambla during the transition, who got drunk at Can Boadas and drank horchata at the Café de l’Òpera, was replaced [in the 80s] by a solitary Rambla, at night, the setting for the most sordid searches, for the saddest flesh or for hard or soft drugs or the whole range of flaccid, censored and uncensored drugs.” (Barcelonas, Barcelona: Ayuntamiento de Barcelona, 2018, p. 330)

“If ever […] you come to this square [Pedró] and it survives, because in the past it was threatened by the creation of another Via Laietana that from Colom to Carrer de Muntaner would sweep away the dark memory of the poor city, I ask you to leave a real or imaginary yellow rose in the fountain, a tribute to the dead that only I remember or only I imagine, who were happy here listening to Clavé’s choir concerts or to the municipal band led by the reprised Lamote de Grignon. Dead people who precede or exceed me, who have not had their chronicle or their hagiographers, buried forever in the common grave of time […] Pre-modern dead who waited uselessly for the consummation of Everything.” (Barcelonas, Barcelona: Ayuntamiento de Barcelona, 2018, p. 350-351)

“…there’s no auditory record left. Once I had to write a radio script on the Barcelona of the period [the 1940s] and I asked the station if they had any recordings of the sound of the trams. They didn’t. And the cries out in the street, the old men singing Machaquito or Rosó, llum de la meva vida… We need a museum of sound; maybe someone has recorded it. The dustman blowing his horn, the sound of a cart’s wheels on the cobblestones. […] There were more smells […] the smell of boiling cabbage was typical; there was the smell of porridge, the smell of the oils which, back in those days, weren’t as refined as they are now. The smell of things frying back in those days could be horrible. Some neighbourhoods stunk of frying. There was a mythology surrounding chicken. That scoundrel Bofarull contributed to it; he owned the restaurant Los Caracoles on Carrer Escudellers. When there was famine, queues of people would form to watch the chickens turn as they were roasted on the street corner. One of the things to do on Sunday was to go to Los Caracoles to see the chickens turning as they were roasted. » (Diàlegs a Barcelona. Manuel Vázquez Montalbán y Jaume Fuster. Barcelona: Ajuntament de Barcelona, 1985, p. 35, 39)

“I did not choose to be born among you

in the city of your terrors

in its vanquished and fugitive south

mediocre trails of hunger and oblivion

I was a shadow of a shadow on the walls

where I was shot with buffers and misgivings

I was born at the tail of the fled army

I stood in the sentry’s light

and I borrowed air and water from you

in neighbourhoods you had too much of. ” (Praga. Barcelona: Lumen, 1982, p. 27)

“Chestnut soufflé. He had bought them out of ritual and nostalgia, in memory of those times his mother roasted chestnuts with an old leaky frying pan, still on the fire of mediocre post-war charcoal or coal dust balls, in the light of carbide, still blindly electric, in that district of the old city now threatened by the good and bad intentions of post-modernity. And next to the chestnuts roasted in a converted frying pan, the sweet potato panellets, the only raw material for confectionery available to all Spaniards. My memories will not survive me, Carvalho said to himself… ” (El laberinto griego. Barcelona: Planeta, 1991, p. 115).

“And in Barcelona’s metamorphosis there was like an exercise of relentless sadism to even destroy the cemeteries of his memory, the physical space where the protagonists of his memories could reside. In Bromuro’s longing […] the survival of the physical space in which he used to find the old man, bars, street corners, the miserable boarding house where he lived, now threatened by the demolition of part of Chinatown, played a key role.” (El laberinto griego. Barcelona: Planeta, 1991, p. 132).

“Casa Leopoldo was the mythical restaurant in Chinatown that Carvalho would go to when he felt nostalgic for the country of his childhood, when he was a miserable little prince in the post-war country. […]The neighbourhood had been pasteurised. The pickaxe began demolishing entire blocks and the lost whores without collars were left without fronts on which to rest their arses during the long waits for economically and psychologically disadvantaged patrons […] It was important that the Olympic voyeur did not take with him from Barcelona the image of sex with varicose veins and inadequate deodorants.” (Sabotaje Olímpico. Barcelona: Planeta, 1993, p. 72)

The author was highly critical of the Games, which he saw as an excuse to trigger the neo liberalisation of a city turned into a commercial brand for sale to global tourists, thus abandoning the democratic demands associated with the neighbourhood movements of the late Franco era and the early stages of the transition. As well as expressing himself in evaluations of considerable analytical acuity, irony, mockery and sarcasm in the face of euphoric construction and the quasi-absolute social consensus surrounding the Games were constant in his treatment of the subject.

“…then the announcement of the Olympics came, which meant undoing any plans for balanced growth. It meant expanding the city according to Olympic needs: creating a road network for rapid communication, and growth towards the Maresme, towards the sea. This wasn’t for the famous conquest of the sea as a poetic achievement, but to conquer the land that would become the Olympic Village, with urban planning conditioned by this need. This also meant that the growth of the city would benefit the part of the city that housed the so-called ‘Olympic’ games. […] The social and cultural graft of the Olympic Village into its setting (beside the Poble Nou, a few metres away from La Mina, the Besós neighbourhoods, etc.) meant that speculation spread out from there.” (Barcelona, cap a on vas? Diàlegs per a una altra Barcelona. Eduard Moreno i Manuel Vázquez Montalbán. Barcelona: Llibres de l’Índex, 1991, p. 59-60)

“[The Olympics] ended up undoing any capacity for resistance or containment that the authorities could have had, even if it seemed like they controlled this process.” (Barcelona, cap a on vas? Diàlegs per a una altra Barcelona. Eduard Moreno i Manuel Vázquez Montalbán. Barcelona: Llibres de l’Índex, 1991, p. 72)

“The Olympic, Pre-Olympic, Trans-Olympic and Post-Olympic Office employed the once less Olympic people of this world […]: from Marxist-Leninism to democratic institutional management and finally to prepare all the Olympics that Spanish democracy would have in 1992: the Fifth Centenary of the Discovery of America, the Seville International Fair, the Olympics, Madrid as the cultural capital of Europe. Those who have not spent half an hour of their lives preparing for the revolution will never know how it feels to find themselves years later prefabricating Olympus and triumphant podiums for athletes of sport, business and industry.” (El laberinto griego. Barcelona: Planeta, 1991, p.32).

“And Nova Icària [a street in the Olympic Village] could be that, a parody of a phalanstery–a phalanstery for the well-to-do, of course. Soon, another initiative might be, for example, a Communist City built by Núñez i Navarro with a whole series of attractions: from an internal gulag for people to spend time in to a ‘cheka’ and an opportunity for people to assault the Winter Palace. All sponsored by the Walt Disney Company.” (Barcelona, cap a on vas? Diàlegs per a una altra Barcelona. Eduard Moreno i Manuel Vázquez Montalbán. Barcelona: Llibres de l’Índex, 1991, p. 105-106)

“…eventually, to move certain projects forward, the City Council abandons its dominion over municipal terrain. All in exchange for compensations that, at the end of the day, don’t hide the fact that the people doing business are the same as always […] In exchange for a small parcel of green space in the city, they’ll earn profits of 1,300 million pesetas.” (Barcelona, cap a on vas? Diàlegs per a una altra Barcelona. Eduard Moreno i Manuel Vázquez Montalbán. Barcelona: Llibres de l’Índex, 1991, p. 116)

“A city occupied by people disguised as healthy can end up being unbearable, particularly if, due to the Olympic Games, the city has undergone cosmetic surgery and important wrinkles of the past have been eliminated from its face.” (Sabotaje Olímpico. Barcelona: Planeta, 1993, p. 12)

A variegated territory of clandestinity and marginality, where the affective, artistic and political expressions repressed by the bien-pensant and bourgeois Barcelona coexist, we find their traces scattered throughout Montalban’s work, from essays to narrative and musicals

“At the Apolo or the Arnau, on Paral·lel, what is now being called the “frivolous genre” triumphed, with legendary canzontistas, vocalists, such as Bella Chelito, Bella Dorita or Raquel Meyer, muse of the erotic dreams of generations of Barcelonians.” (Barcelonas, Barcelona: Ayuntamiento de Barcelona, 2018, p.183)

“The name [Chinatown] also makes sense as an extension of the concept of a forbidden neighbourhood, because of its status as a territory for the underworld and the lumpen. Barcelona’s Chinatown invaded Escudillers street and its surroundings, like a criminal brand, but its heart was and is on the other side of the Rambla, between Drassanes, Paral·lel and Hospital street. There, whores and working-class families, queer employees and union members of the newborn socialist and communist formations, women’s prisons and Basque gables, condom shops and furniture smelling of disinfectant and English, beach bars selling fine and generous wines with cazalla or barrecha (cazada and muscatel), one of the first cultural syntheses of the connection between the Catalan people and the emigrants, all mixed together.” (Barcelonas, Barcelona: Ayuntamiento de Barcelona, 2018, p. 188)

“This is the Church of Carmen. It was built after the Tragic Week, on the site of a former Hieronymite convent that was burnt down by the revolutionaries. (El pianista, Barcelona: Seix Barral, 1985, p. 33)

“Scene VIII

Panorama of the Paral·lel in the 1920s. Reynals, Patrick and Arrufat come into view in black tie, top hats, etc. They are quite drunk.

Patrick:

I’m confused

In awe,

Horrified,

Overcome,

Splitting my sides,

Blown away,

I’m just

In love with

This city.

On the same day, in the

Same place,

I met

A drunk dictator

Who didn’t dictate a thing.

An Andalusian who’s a

A mad painter

From the Empordà

Who, right in front of me,

Masturbated

Into an envelope

And sent

The results

To his father

Saying: I don’t owe you

A thing.”

(Flor de nit / text Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, sobre una idea de Dagoll Dagom; música Albert Guinovart. Alicante : Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes, 2000, p. 60-62.https://www.cervantesvirtual.com/obra/flor-de-nit-multimedia–0/)

“Scene XII

Quimet’s attic […]

Pons:

Are you guys

Really anarchists?

Or are you regional

Nationalists?

Our final

Struggle

Must be

International

For the victory of the

Proletariat!

Quimet, Pons:

No more kings,

And we still have a king.

Isadora:

And no more clients,

And we still have clients.

No more gods…

Revolution!”

(Flor de nit / text Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, sobre una idea de Dagoll Dagom; música Albert Guinovart. Alicante: Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes, 2000, p. 60-62. https://www.cervantesvirtual.com/obra/flor-de-nit-multimedia–0/)

The author’s assessment of Franco’s entry into Barcelona and its effects leaves no room for doubt:

“Repression was fierce, relentless, merciless.” (Barcelonas. Barcelona: Ajuntament de Barcelona, 2018, p. 243)

“The mood against this background went through ideological neighbourhoods, although it increasingly translated into economic situations: the established Barcelona, with the exception of the culturally nationalist areas, became Francoist to a greater or lesser degree; the other Barcelona ate its own memory or adapted its metabolism to the ingestion of toads and stood firm at dusk, when the flag was lowered in the barracks, profusely scattered around the city, and woe betide anyone who did not stand firm with arms raised at the sound of silence! Once again there was a dual consciousness […]: the city that survived and pretended not to be aware of the shots being fired, of the queues outside the Modelo [prison], of the systematic destruction of its own identity.” (Barcelonas. Barcelona: Ajuntament de Barcelona, 2018, p. 249)

His poems delved into the expression of the experience of that “other” losing Barcelona:

“O city of terror

among the livid avenues

autumn trees

the invaders

shot records

drunk with barbaric memory

fed up with flesh humiliated

and offended

fear was a presence

silence its shroud

words hidden in things

ideas in the eyes

contemplated

the division between the one who dies and the one who kills” (Praga. Barcelona: Lumen, 1982, p. 15)

“Definitely nothing left of April

the cruellest month, poor Rosa de Abril

drawn with death – hypothesis of death –

between my hands your cold face confirmed

the silence to which you bring my memory

the memory of my childhood and your post-war

your youth assaulted by the dogs of History

my youth assaulted by your instinct of life

red Rosa […] ” (Pero el viajero que huye. Madrid: Visor, 1991, p. 59)

Symbolic resistance and solidarity remain to counter the terror and misery in these defeated neighbourhoods:

“Get out of this shitty country and start thriving. […] Either you go or you burst. Sometimes I look over to that side, the one that points towards Calle de la Cera and the Padró cinema, and I imagine I’m up here with a machine gun and all the fascists in Spain pass through that street and ratatatatatata, I don’t leave a single one and it feels good to let off steam. If you ever see me get up there and machine-gun with my mouth, don’t pay me any attention. I’m letting off steam.” (El pianista, Barcelona: Seix Barral, 1985, p. 107)

“The boy circles around a sleeping dog that from time to time opens one eye to watch the bicycle’s intentions.

—Here on the roof he enjoys himself and frees himself from all the shit that the nuns put in his head. My brother-in-law has balls. Red for life. Prison. And he goes and puts my little boy in a school run by the nuns of San Vicente de Paúl, by the Savings Bank, because it’s free, and for the time being, for what they teach him… Well, they teach him to pray. And do you know what book they’ve given him to read at home? Fabiola. A book about martyrs, priests and Romans. I ask Young who Fabiola is, baby.

—A bad whore.” (El pianista, Barcelona: Seix Barral, 1985, p. 109)

“The other day a poor woman came in, full of shit, pardon me, she was carrying a child and asked for something to eat. Without opening the door, I told her through the peep hole to go to the stairs and wait. I saw them sitting on the stairs and I opened the door a little, just enough to put a plate of rice on the floor with a spoon. I closed the door again and through the peep hole I saw them eating it. They left the plate and spoon in the same place and when I was sure they had gone, I went out and retrieved the plate. It was a case of need and they were very hungry, very hungry to eat that rice, because it had been in the cooler for several days and it smelled a bit. It had turned out really good.” (El pianista, Barcelona: Seix Barral, 1985, p. 117-118)

“I told you that the bookseller in Atarazanas was beginning to trust me. Then he told me that, first of all, he always puts the clients in isolation, lest they become police accomplices. The other day, an old bookseller in Hospital Street was caught with Blasco Ibáñez’s La araña negra and Nietzsche’s Así hablaba Zarathustra and was taken to [the police station on] Vía Layetana.” (El pianista, Barcelona: Seix Barral, 1985, p.125)

Vázquez Montalbán was also extremely critical of the great urban transformations in Barcelona which, with Franco’s developmentalism, changed its appearance in the 50s under the leadership of Mayor José María de Porcioles:

“Porciolism set loose the fervour of growth. It led to an empire of repressive urbanism based on the city as a place for transit (the faster the better), as a basis for a construction industry that was attractive enough for the development of an urban capitalism. This all led to the destruction of a city made of pleasant spots, a city that was a place to be, to stroll, to interact with others, etc. Porciolism is the maximum representation of a repressive urbanism of anti-communication. […] After the Spanish Civil War, what Oriol Bohigas calls ‘black market architecture’ found its fundamental political element in Mr Porcioles, and particularly in Porciolism as an urban philosophy.” (Diàlegs a Barcelona. Manuel Vázquez Montalbán y Jaume Fuster. Barcelona: Ajuntament de Barcelona, 1985, p. 54-56)

“…All of a sudden, in the late 1950s and early 1960, it [Cornellà, Santa Coloma, Sant Vicenç dels Horts] was all invaded by horrible blocks of buildings. Of course people needed a place to live, but according to what criteria? Savage criteria. The people who went there to live paid a huge price in their way of life, with psychological, social and personal problems of all sorts.” (Barcelona, cap a on vas? Diàlegs per a una altra Barcelona. Eduard Moreno i Manuel Vázquez Montalbán. Barcelona: Llibres de l’Índex, 1991, p. 85-86)

“…the Barcelona of Porcioles, that vast impersonal car park.” (Barcelonas, Barcelona: Ayuntamiento de Barcelona, 2018, p. 350)

Vázquez Montalbán confirmed that the anti-Francoist work of the Asociaciones de Vecinos (Neighbourhood Associations) was fundamental against porciolismo:

“Barcelona […] already had a critical, political and ideological brew that was quite strong in the 1960s. And what was its outlet? The neighbourhood associations. […] This was one of the most important cultural phenomena in all of Spain: the appearance of an urban critique in the Barcelona of the late 1960s and early 1970s tied to these movements.” (Barcelona, cap a on vas? Diàlegs per a una altra Barcelona. Eduard Moreno i Manuel Vázquez Montalbán. Barcelona: Llibres de l’Índex, 1991, p. 42)

A central element of Montalban’s vision of this period is his critique of how the politicians who led the transition from dictatorship to democracy agreed to grant impunity for the crimes of Francoism and to limit the much more ambitious demands of the anti-Franco left to a framework of liberal capitalist democracy. There are frequent characters within the pages of his work who are political actors with a left-wing past that had a change of heart or went back to their parents’ house.

“—It’s funny. At almost every table a familiar face. The generation in power: between thirty-five and forty-five years old. Those who knew how to stop being Francoists in time and those who knew how to be anti-Francoists in the right measure or at the right time.” (El pianista, Barcelona: Seix Barral, 1985, p. 57)

“[…] we created a fight that we didn’t make. Francoism lasted as long as it had to last, and it overrode what we called our fight.

—But at least we helped to raise democratic awareness.

—As well as Opus initiating the Stabilisation Plan in nineteen fifty-seven and then Economic Development.

—And banning Last Tango in Paris.

—But allowing the bourgeoisie to queue up in cars all the way to Perpignan to see Marlon Brando’s bottom. It was a perfectly assumed dual attitude. Instead, we went forward with the battering ram to demolish the Bastille fortress and we didn’t demolish anything.

—Delapierre, you who are an actor, lecture Joan not to be so revisionist. Revisionists block my brain.

—Joan isn’t a revisionist. She has simply grown up.[…]

—There is a time to make a mistake and time to discover the reason why. But I don’t regret anything I’ve done.” (El pianista, Barcelona: Seix Barral, 1985, p. 56)

“—And you, what?

—Me? What about?

—Politically, boy. I offer an explanation of the correlation of forces present. Joan and Mercè belong to the civilised right, while Delapierre is an activist and a member of the Frente de Liberación Gai (Gay Liberation Front). […] Ventura, your old rival in the conquest of power within the PSUC (Unified Socialist Party of Catalonia), the EBU (European Broadcasting Union), the PCI, Red Flag and again the PSUC, that is to say, wherever we have been, the combative and brilliant old Ventura has become… sceptical… […] And Luisa is a left-wing nationalist and a feminist […]

—And you, Schubert?

—I hesitate between playing along with the socialists to make a run for it and being able to save for my old age, or retiring to my ideological possessions of the past and waiting for better times. —And you? […]

For you, they have changed the song, master. You belong to the fugitives of Marxist knowledge, to the troop that lends language and information to international capitalism, language, information and logic of the enemy and also the satisfaction of having recovered you, master.” (El pianista, Barcelona: Seix Barral, 1985, p. 65, 67-68)

Although Vázquez Montalbán’s criticism is Spanish in scope, it is often embodied in characters from Barcelona, as in the cases cited above from El pianista. Thus, this criticism is very well articulated with the city in his work, thanks to the author’s extensive knowledge of the socio-economic and urban realities of Barcelona:

“I should acknowledge that there have been some programs aimed at recuperating free space within the city, particularly in the most densely populated areas. The opening of the city towards the sea through the Moll de la Fusta and other initiatives represent a certain attempt to recover public space. I’ve also noticed an effort to restore neighbourhood culture, neighbourhood identity. This was a very positive achievement of democracy. However, we are part of a market, and speculation cannot be fought within this framework. The city may have a more advanced, democratic policy of urban culture, but it’s set within the framework of the free market. As a result, developers have the law on their side.” (Diàlegs a Barcelona. Manuel Vázquez Montalbán y Jaume Fuster. Barcelona: Ajuntament de Barcelona, 1985, p. 56)

“The installation of socialists in municipal power allowed many intellectuals and critical professionals from the previous period to stop thinking about the city in order to make it, to enter the temple of actual management, and the impact between reality and desire forced a pragmatic synthesis, favoured – and induced – by dismantling the critical conscience represented by the neighbourhood movement.” (Barcelonas, Barcelona: Ayuntamiento de Barcelona, 2018, p. 334-335)

“What worries me at the end of this theoretical trip (on their part, more ideological than theoretical) is alienation. In other words, I think that at the moment they believe what they’re saying because they need to believe in it. If not, they would have to undergo such a harsh process of self-criticism that it would put a great many things in question. Therefore, they would rather say that there were no other options. And since there’s no way to demonstrate it, this is the problem with the opposition between pragmatic individuals and those who are accused of being utopian. Pragmatic individuals can say: “We did this”, but utopian individuals have to say: “Go look at the newspaper archives to see what we said at the time.” That’s a constant failure. Now nobody will ever think about what that city could have been like. Nobody will be able to consider it, because, of course, it’s an unequal struggle between pragmatic individuals and critical individuals.” (Barcelona, cap a on vas? Diàlegs per a una altra Barcelona. Eduard Moreno i Manuel Vázquez Montalbán. Barcelona: Llibres de l’Índex, 1991, p. 66)

“I’m quite concerned about the hugs Maragall and Pujol give Porcioles […], accepting the systematic destruction of the city that Porciolism represented. […] I’d like to know whether those hugs represent a shared philosophy or a shared vision for the city: the Great Barcelona.” (Diàlegs a Barcelona. Manuel Vázquez Montalbán y Jaume Fuster. Barcelona: Ajuntament de Barcelona, 1985, p. 54)

Vázquez Montalbán said that his homeland was his childhood, the space-time of a poor Barcelona neighbourhood of losers in the first post-war period. References to it run through his bibliography, marked by nostalgia, a tone of vindictive tribute and criticism of an urbanism that despises the imprint of the past in the city.

“There was even a custom –I remember this from my childhood, since I lived in the 5th district– where strolling on Sundays meant walking up and down the Rondes, the Paral·lel and the Rambla. We never left this circuit, because beyond it stood the Eixample, another territory that belonged to another social sector.” (Barcelona, cap a on vas? Diàlegs per a una altra Barcelona. Eduard Moreno i Manuel Vázquez Montalbán. Barcelona: Llibres de l’Índex, 1991, p. 15-16)

“The boiling citizen of the Rambla during the transition, who got drunk at Can Boadas and drank horchata at the Café de l’Òpera, was replaced [in the 80s] by a solitary Rambla, at night, the setting for the most sordid searches, for the saddest flesh or for hard or soft drugs or the whole range of flaccid, censored and uncensored drugs.” (Barcelonas, Barcelona: Ayuntamiento de Barcelona, 2018, p. 330)

“If ever […] you come to this square [Pedró] and it survives, because in the past it was threatened by the creation of another Via Laietana that from Colom to Carrer de Muntaner would sweep away the dark memory of the poor city, I ask you to leave a real or imaginary yellow rose in the fountain, a tribute to the dead that only I remember or only I imagine, who were happy here listening to Clavé’s choir concerts or to the municipal band led by the reprised Lamote de Grignon. Dead people who precede or exceed me, who have not had their chronicle or their hagiographers, buried forever in the common grave of time […] Pre-modern dead who waited uselessly for the consummation of Everything.” (Barcelonas, Barcelona: Ayuntamiento de Barcelona, 2018, p. 350-351)

“…there’s no auditory record left. Once I had to write a radio script on the Barcelona of the period [the 1940s] and I asked the station if they had any recordings of the sound of the trams. They didn’t. And the cries out in the street, the old men singing Machaquito or Rosó, llum de la meva vida… We need a museum of sound; maybe someone has recorded it. The dustman blowing his horn, the sound of a cart’s wheels on the cobblestones. […] There were more smells […] the smell of boiling cabbage was typical; there was the smell of porridge, the smell of the oils which, back in those days, weren’t as refined as they are now. The smell of things frying back in those days could be horrible. Some neighbourhoods stunk of frying. There was a mythology surrounding chicken. That scoundrel Bofarull contributed to it; he owned the restaurant Los Caracoles on Carrer Escudellers. When there was famine, queues of people would form to watch the chickens turn as they were roasted on the street corner. One of the things to do on Sunday was to go to Los Caracoles to see the chickens turning as they were roasted. » (Diàlegs a Barcelona. Manuel Vázquez Montalbán y Jaume Fuster. Barcelona: Ajuntament de Barcelona, 1985, p. 35, 39)

“I did not choose to be born among you

in the city of your terrors

in its vanquished and fugitive south

mediocre trails of hunger and oblivion

I was a shadow of a shadow on the walls

where I was shot with buffers and misgivings

I was born at the tail of the fled army

I stood in the sentry’s light

and I borrowed air and water from you

in neighbourhoods you had too much of. ” (Praga. Barcelona: Lumen, 1982, p. 27)

“Chestnut soufflé. He had bought them out of ritual and nostalgia, in memory of those times his mother roasted chestnuts with an old leaky frying pan, still on the fire of mediocre post-war charcoal or coal dust balls, in the light of carbide, still blindly electric, in that district of the old city now threatened by the good and bad intentions of post-modernity. And next to the chestnuts roasted in a converted frying pan, the sweet potato panellets, the only raw material for confectionery available to all Spaniards. My memories will not survive me, Carvalho said to himself… ” (El laberinto griego. Barcelona: Planeta, 1991, p. 115).

“And in Barcelona’s metamorphosis there was like an exercise of relentless sadism to even destroy the cemeteries of his memory, the physical space where the protagonists of his memories could reside. In Bromuro’s longing […] the survival of the physical space in which he used to find the old man, bars, street corners, the miserable boarding house where he lived, now threatened by the demolition of part of Chinatown, played a key role.” (El laberinto griego. Barcelona: Planeta, 1991, p. 132).

“Casa Leopoldo was the mythical restaurant in Chinatown that Carvalho would go to when he felt nostalgic for the country of his childhood, when he was a miserable little prince in the post-war country. […]The neighbourhood had been pasteurised. The pickaxe began demolishing entire blocks and the lost whores without collars were left without fronts on which to rest their arses during the long waits for economically and psychologically disadvantaged patrons […] It was important that the Olympic voyeur did not take with him from Barcelona the image of sex with varicose veins and inadequate deodorants.” (Sabotaje Olímpico. Barcelona: Planeta, 1993, p. 72)

The author was highly critical of the Games, which he saw as an excuse to trigger the neo liberalisation of a city turned into a commercial brand for sale to global tourists, thus abandoning the democratic demands associated with the neighbourhood movements of the late Franco era and the early stages of the transition. As well as expressing himself in evaluations of considerable analytical acuity, irony, mockery and sarcasm in the face of euphoric construction and the quasi-absolute social consensus surrounding the Games were constant in his treatment of the subject.

“…then the announcement of the Olympics came, which meant undoing any plans for balanced growth. It meant expanding the city according to Olympic needs: creating a road network for rapid communication, and growth towards the Maresme, towards the sea. This wasn’t for the famous conquest of the sea as a poetic achievement, but to conquer the land that would become the Olympic Village, with urban planning conditioned by this need. This also meant that the growth of the city would benefit the part of the city that housed the so-called ‘Olympic’ games. […] The social and cultural graft of the Olympic Village into its setting (beside the Poble Nou, a few metres away from La Mina, the Besós neighbourhoods, etc.) meant that speculation spread out from there.” (Barcelona, cap a on vas? Diàlegs per a una altra Barcelona. Eduard Moreno i Manuel Vázquez Montalbán. Barcelona: Llibres de l’Índex, 1991, p. 59-60)

“[The Olympics] ended up undoing any capacity for resistance or containment that the authorities could have had, even if it seemed like they controlled this process.” (Barcelona, cap a on vas? Diàlegs per a una altra Barcelona. Eduard Moreno i Manuel Vázquez Montalbán. Barcelona: Llibres de l’Índex, 1991, p. 72)

“The Olympic, Pre-Olympic, Trans-Olympic and Post-Olympic Office employed the once less Olympic people of this world […]: from Marxist-Leninism to democratic institutional management and finally to prepare all the Olympics that Spanish democracy would have in 1992: the Fifth Centenary of the Discovery of America, the Seville International Fair, the Olympics, Madrid as the cultural capital of Europe. Those who have not spent half an hour of their lives preparing for the revolution will never know how it feels to find themselves years later prefabricating Olympus and triumphant podiums for athletes of sport, business and industry.” (El laberinto griego. Barcelona: Planeta, 1991, p.32).

“And Nova Icària [a street in the Olympic Village] could be that, a parody of a phalanstery–a phalanstery for the well-to-do, of course. Soon, another initiative might be, for example, a Communist City built by Núñez i Navarro with a whole series of attractions: from an internal gulag for people to spend time in to a ‘cheka’ and an opportunity for people to assault the Winter Palace. All sponsored by the Walt Disney Company.” (Barcelona, cap a on vas? Diàlegs per a una altra Barcelona. Eduard Moreno i Manuel Vázquez Montalbán. Barcelona: Llibres de l’Índex, 1991, p. 105-106)

“…eventually, to move certain projects forward, the City Council abandons its dominion over municipal terrain. All in exchange for compensations that, at the end of the day, don’t hide the fact that the people doing business are the same as always […] In exchange for a small parcel of green space in the city, they’ll earn profits of 1,300 million pesetas.” (Barcelona, cap a on vas? Diàlegs per a una altra Barcelona. Eduard Moreno i Manuel Vázquez Montalbán. Barcelona: Llibres de l’Índex, 1991, p. 116)

“A city occupied by people disguised as healthy can end up being unbearable, particularly if, due to the Olympic Games, the city has undergone cosmetic surgery and important wrinkles of the past have been eliminated from its face.” (Sabotaje Olímpico. Barcelona: Planeta, 1993, p. 12)

Contributions

Audiovisuals

Los siete locos. Canal 17 Argentina. 2005. 37.20 – 37.54

Lejos de mí tan lejos. ACEC. 22 d’abril del 2003

Perfils Catalans: Manuel Vázquez Montalbán (in Catalan with subtitles in Spanish). Tranquilo produccions per a TVE, 26 min., 26 min.

Adiós a Manuel Vázquez Montalbán. Informe semanal 18/10/03. RTVE. A report by Sylvia Fernandez de Bobadilla and Gabriel Laborie

Vázquez Montalbán – Presentación. ACEC. April 22th 2003