CrIME novel

Text and selection of content: Javier Rivero

The world of Carvalho

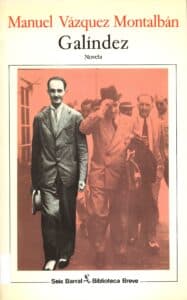

Manuel Vázquez Montalbán was the great pioneer in introducing the crime novel to Spain. The adaptation he made of the genre from the end of the dictatorship to the beginning of the new millennium served as a chronicle of Spain’s socio-political situation and encouraged other authors to cultivate the crime novel.

Manuel Vázquez Montalbán at the Planeta Novel Prize in 1979.

Manuel Vázquez Montalbán with Pepe Martín and Maruja Torres celebrating the 25th anniversary of Carvalho.

Novels of Carvalho

Selection of texts

“I didn’t want to take off my jacket so he wouldn’t see the gun under my armpit. Not because of the gun, nor because of the images of crude violence that it could inspire, but because of the ugliness of the strap that held the holster, like a gloomy invalid’s corset. But I was hot. It’s even likely it was hot. I got up with dissimulated keenness to get closer to the lattice window. On the lawn, the Kennedy family were eating sandwiches. Night was falling. The water in the swimming pool recovered a false tranquillity beneath the grey shadows. A black domestic servant fished for floating dead leaves. Robert Kennedy was doing a handstand and his two eldest children were imitating him. I looked, hesitated, looked again. John Fitzgerald Kennedy was smoking a very long peace pipe from the top of a horse chestnut tree. The shadow of a cloud brought on nightfall. The skin of the bodies grew darker, the skin of the world. Abrupt whiteness was distilled from the Kennedys’ collective teeth. Jacqueline’s voice reached me like a companion I was starting to need.

“Do you think our surveillance system won’t be enough to detect Carvalho?”

“You don’t know the Galicians.”

“Oh, yes I do. I know one or too. A warehouse worker in Detroit and one of Adlai´s cooks. I didn´t notice anything special about them. For the moment they´re not invisible.”

“They´re dangerous and obstinate, like the Jews.”

Jacqueline, with one finger, sealed my lips on hers, while she looked suspiciously at the non-existent corners of the circular room.

“Shut up, please.”

“Queta´s mature flesh fitted better in the framework than the little work of Teresa’s body. What Carvalho could not imagine was the sensations that would pass through the body of a hairdresser from District V in that sanctuary set aside for the repose of an unknown social class. Carvalho remembered how the forties suddenly opened as the miracle of the Plaza de Padró resulting from the crossroads of different streets of District V. He remembered the songs that went up through the inner courtyards to the hum of sewing machines or amid the clatter of the plates hitting the bowls. And he remembered that song sung again and again, mostly by women of the age Queta was now:

“He arrived on a ship with a foreign name and I met him in the harbour at nightfall…”

It was love with a stranger “blond and tall as beer,” “chest tattooed with a heart.” Julio had found in Queta for the first time a psychologically inferior woman who did not give him culture or new experiences, who simply asked him for communication, solidarity, even personal enrichment, something that he could give her, and mystery of youth and distance that in Mr. Ramón were definitely dead and buried.

“We private detectives are the thermometers of established morality, Biscuter. I tell you this society is rotten. It doesn’t believe in anything.”

“Yes, boss.”

Biscuter didn’t tell Carvalho he was right only because he guessed that he was drunk, but because he was already to admit catastrophes.

“Three months and not a sausage. Not one husband looking for his wife. Not one father looking for his daughter. Not one bastard who wants proof that his wife is cheating on him.” “Don’t women run away from home anymore? Or girls?” “Yes, Biscuter. More than ever. But nowadays their husbands and fathers couldn’t care less if they run away. They’ve lost the basic values.” “Didn’t you want democracy?”

“I didn’t mind either way, boss.”

“He saw them on a dune in decline, a few metres from the coming and going of the cold waters of the open Mediterranean, with their backs to the warm waters of the enclosed Mar Menor. She was lying on the sand, wearing a blouse, but without a skirt and the man’s head rested on her lap to be stroked by a female hand to the rhythm of the waves. But from Carvalho’s perspective it was clear that they were not alone. Towards his dune came the corpulent and irremediable body of a man covered with a hat. Carvalho got out of the car, but turned back to it to pull the gun out of the glove compartment, remove the safety catch and wield it before starting a race to the scene that was about to happen. He watched in slow motion as the man in the hat stopped and raised his arms pointing a rifle at the couple and Carvalho shouted Teresa’s name with all his might, a name that became a stone of words that smashed the human balance of the landscape. Teresa arched backwards on herself, Archit jumped to his feet, the man in the hat turned to Carvalho to show him for a moment his “Jungle Kid” face with his eyes furrowed by the decision and then turn back to the couple and point at them. Archit opened his arms and shielded Teresa’s body with his thin boy’s body, to receive a bullet that made him double over, bend forward, and fall limply. Carvalho fired and the bullet lifted dune sand a few metres beyond “Jungle Kid”, who turned and fired at Carvalho and then ran in the direction of a waiting car. Carvalho gave himself the order to wipe his forehead with his hand and then found it full of blood. It didn’t hurt, but he knew he had been hit. He ran towards the Pietá composed of a strident Teresa Marsé who was crying and cursing, cradling Archit’s body on the sand and, when she saw Carvalho arrive, she was slow to recognise him through a barrier of hatred and fear. Carvalho was marked. He knelt down next to Archit, laid him down on the sand, confronted the spectacle of his eyes wandering through the sky in search of a handhold so as not to fall into the pit of death. Carvalho looked up at the sky in the hope of helping Archit find the handhold, the two of them heedless to the woman’s wise heartbreaking sobs. But in the sky there were only flocks of birds scared away by the shots fired by the men and Carvalho believed he had a duty to dispel any doubts Archit might have.

“Swallows. They’re swallows.”

Archit’s lips strove to say something before surrendering to the rigidity of death. Carvalho was convinced that they had tried to repeat the name of the birds, to recognise the birds and, with them, of the great homeland of the skies.”

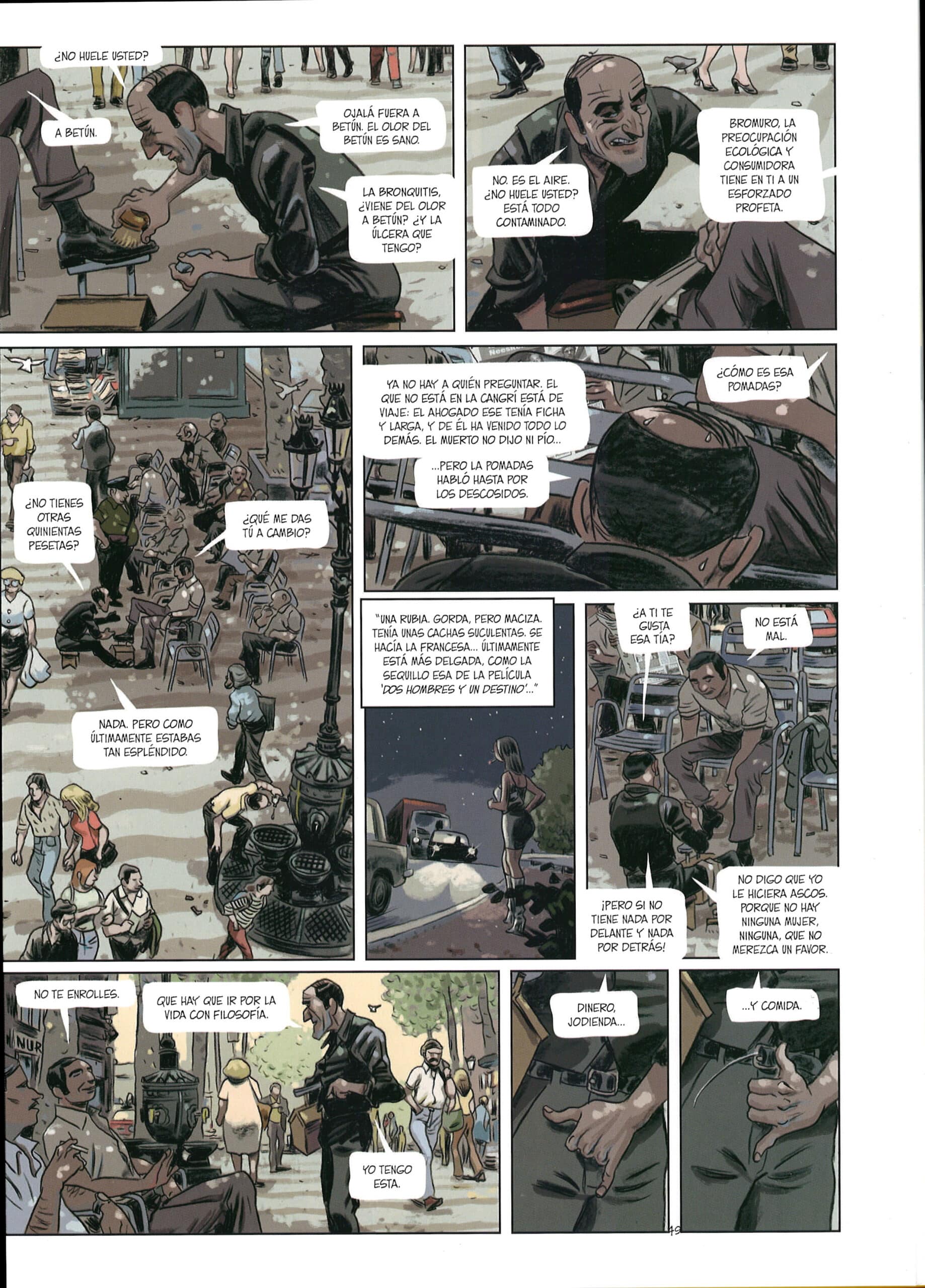

He didn’t find “Bromuro” in his place of work on the corner of Escudellers Street, nor in the bars and clubs in the area, nor had he left any message in the office. In a bar on Arc del Teatre Street, they hinted at the possibility that he had been taken away in the raid the night before, but “Bromuro” was an individual known to the police and would not be held in a police station more than the strict time of identification. In the boarding house where the shoeshine slept they had not seen him for days, although the owner believed prevention was better than cure and shouted to Carvalho that she was not up to date on the comings and goings of that old, lazy waster who yet again owed her five months’ rent, and one day when he returns he will find the cardboard box on the stairs. From what the landlady then clarified, the cardboard box was the one that had been used to bring the landlady’s colour television and “Bromuro” had asked her to put all his belongings in it.

The lights on the Ramblas were coming on when “Bromuro” knocked on the door of Carvalho’s office and asked for something strong to regain speech and dignity.

“I’ve lost everything in one night, Pepe. I can die now.

Biscuter was more alarmed than Carvalho by the sudden pessimism of the bearded, dirty, dishevelled shoeshine in what remained of the viscous tapestry of his parietals.

“They grabbed me last night, Pepiño, in the raid, a young lieutenant of those they come up with from who knows where and I smiled, this guy will see what will happen the “Bromuro” appear in the police station. And as soon as I arrived I go to the guy on duty and I identify myself. Nothing. As I had told him a petty criminal was there. The guy didn’t even look at me. I demanded that Miraflores or Contreras come out, you know who I’m talking about. He said Miraflores had retired and Contreras didn’t care, he was busy with something else. And me with my balls fuller than Bernarda’s cunt, I roll out my background, my service with the Blue Division and more confident than God himself in the glorious times in which the streets were full of gunmen. So no way, a runt straight out of the police academy and he tells me those merits have expired and he tells me with his little beard and his face of a red [communist] by correspondence course, I can smell those guys a mile off, and me, a real red, a lifelong communist, I respect that, but not some upstart copper and red or democrat to boot, or some unnatural mixture of the above, no way. And he just ignores me there and less and less, man, Pepe, I’m telling you straight up, because I thought to myself, all those bullets, all that going round with no shirt on, stark naked, and then in the end they won’t even accept you as an informer.

…

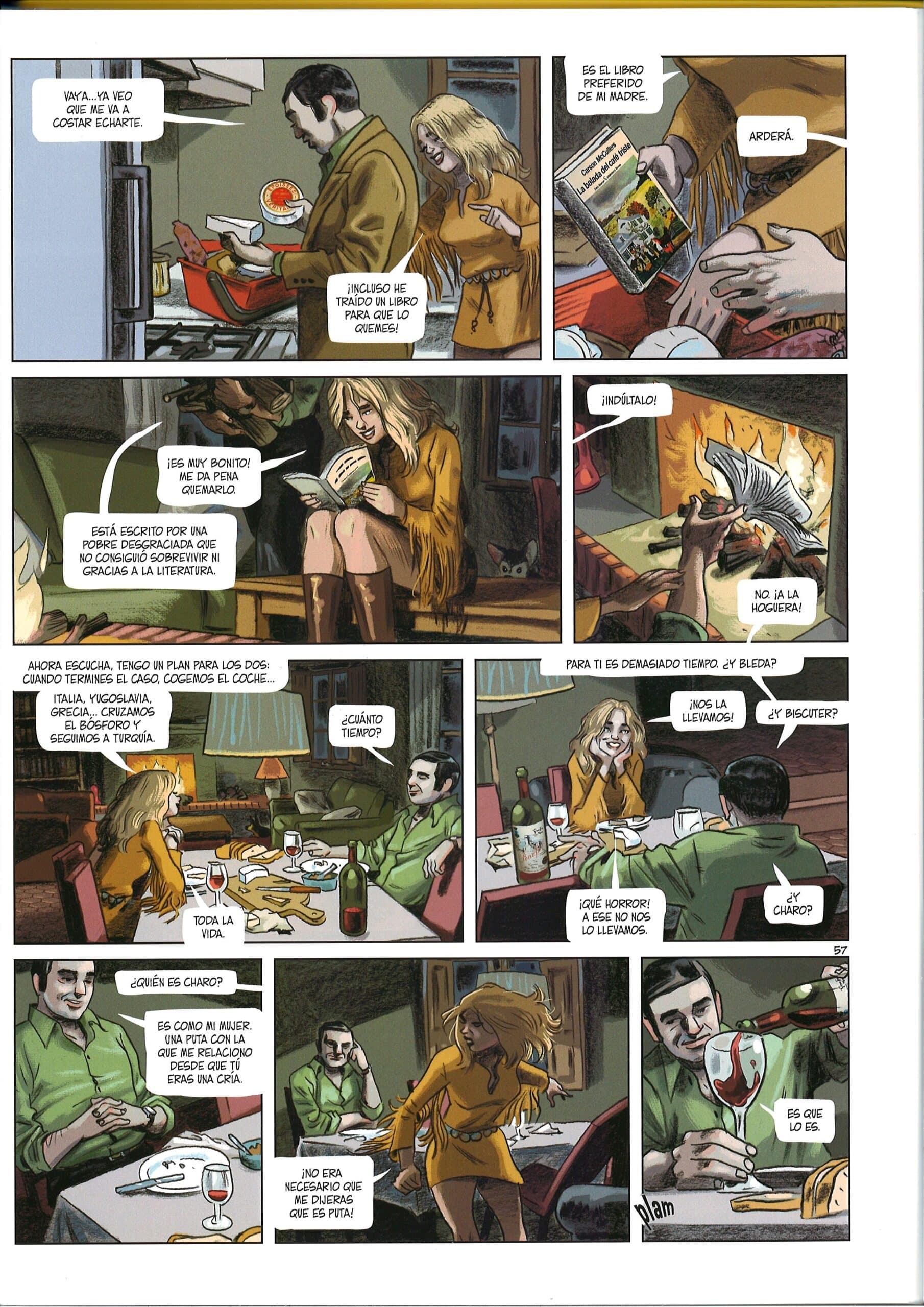

“It wasn’t scepticism that the manager’s raised eyebrows expressed, with his dark blue Greek sailor’s cap and the grey head of hair supporting the tilt of his head on the saucepan in which Carvalho was putting the finishing touches to his cooking.

“An extra dinner to celebrate what?”

“The impossibility of celebrating anything.” I had felt generous or old and I had offered Charo the option of moving in with me, on a trial basis, for a while, then, who knows. But after thinking about it, not for long, half a minute, she said no, that each person is each person, that she cooks worse than me, that she does her own thing. And with that she left. Also what has happened to me is what happened, me with that idiotic idea of saving the life of a killer who in every way is inadequate and dull. And in those cases there’s nothing like going to the Boqueria to buy stuff you can manipulate and turn into other stuff: vegetables, shellfish, fish, meat. Lately I’ve been thinking about the horror of eating, in relation to the horror of killing. Cooking is an artifice of covering up a savage killing, sometimes perpetrated in conditions of savage, human cruelty, because the supreme adjective of cruelty is ‘human’. Those little birds drowned alive in wine so that they taste better, for example.

“An excellent topic of conversation as an appetiser.

Nineteen eighty-four has only just started. The stars are in alignment and they will shaft us, one after another. It will be a bad year, according to the astrologers. So for that reason and for many others, I went to the Boqueria to get some groceries, ready to cook for myself.

“And for Fuster, for the guinea pig.”

“You’re free to eat it or not.

But above all don’t reject the first course, a meeting between cultures, spinach lightly cooked, drained, chopped and then a gratuitous and absurd artifice, like all culinary artifice. Fry the heads of some prawns in butter. The heads are set aside and with them a light broth is made. Sauté carved garlic, pieces of shrimp and shelled and seasoned clams in the flavoured butter. That dressing is poured over the spinach and let everything cook together, not long, enough for it to aromatise and acquire an unctuous moisture that enters through the eyes. This dressing is poured over the spinach and we leave it all to cook together, not too long, just enough for the aroma to develop and for it to gain a smooth moisture that enters through the eyes. Then we add small kid goat legs, basic, routine, small legs fried till golden in lard, with an onion and cloves, a tomato, mixed herbs. We add the chopped bacon to this base, the liquid from scalded greengages and we make a sauce that evokes the Spanish one, but with a predominant clove aroma, the sugars released by the kid goat legs and the bacon. The scalded plums are arranged on the goat legs, we pour the sauce over that, a brief spell in the oven, and dinner is served. A couple of bottles of Remelluri de Labastida, 78 vintage, and aged with dignity.

“And you get paid for not solving cases?”

“I always solve them. I always get to know almost as much as the murderer and I tell my client everything.

Even in the last case in which my client knew more than I did and always will, he even knows more than the murderer, but it’s as if he didn’t.”

“Biscuter, what would you do to find out the real identity of a dead man, suspecting at the same time that, besides being an assumed name, his face will not be recognised by any sensible Spaniard because he has predictably been living in Mexico for the last forty years?

Biscuter has furrowed his brows concentrating on the question while shaking the shaker.

“Are you asking me, Boss, seriously?

“Yes.”

Well, I would publish a photo of the dead guy in the Mexican press and wait for someone to come forward, a family member or a friend, who recognises the photograph.”

“Biscuter, you have proposed exactly what I have just done. I hope that the Aeromexico pilot I gave the photos to doesn’t go and crash and that they reach their destination.”

“Don’t exaggerate, boss. If the plane crashes, much more would be lost than the photographs. Have you been to Mexico?”

“Yes.”

“Is it such a sick country as they say?”

“It’s a beautiful country.”.

“You could have sent me with the photographs. I never travel, boss. You promised to send me to Paris to do a cookery course, to specialise in soups, and you haven’t sent me.”

“I need to get paid by Nero Wolfe to send you to Paris, Biscuter. But as soon as a murder case comes up and my client is a travel agency, I promise I will ask them to pay you in kind and you will go to Paris. Biscuter, I swear.”

Biscuter is not very convinced. He stops shaking the cocktail shaker, uncorks it and carefully pours a little stream of liquid in a cocktail glass.

“A gimlet, boss, like in the movies.”

Carvalho tastes it.

“You overdid the lime syrup, Biscuter.!

“I’ll add more gin.”

“The gin isn’t right either.” It seems too sweet.

“Today’s not my day.”

Carvalho is paying more attention to the phone than to Biscuter’s self-pity, crestfallen because he never gets any praise, always criticism, always criticism. I made him some baby squid in beer, bloody marvellous, and he still hasn’t told me if he liked them. On the other end of the phone the results are coming in of the people consulted in Carvalho’s search. Sects that existed during the [Spanish] Republic and the Civil War. Finally, an ex-university classmate gives him a lead: Evaristo Tourón, the leading specialist in the conduct of sects during the war. He won’t come to the phone: he’s a real wise man. Real wise men never answer the telephone. Can you imagine Einstein on the phone? Evaristo Tourón has his ivory tower in a villa in the scenic location of Permanyer, an island in the rectangular and grey chessboard of the Ensanche district of Barcelona, fifty metres away from the traffic jams, in a microclimate of silence and subdued palm trees.”

“Sometimes they pay me without fucking and then they don’t leave me a tip. Signs, Pepe, signs that this is coming to an end and I will be fifty with more makeup than ever, with more creams than ever, waiting next to the telephone for someone to call me and you don’t call me. It wouldn’t have been better if I had told you in person what I’m going to tell you. I see it very clearly. Better to put it in writing and you remember me as I was, as we were the last afternoon you took me for a walk to get my nerve out or on that trip to Paris that, finally, we made last spring. Remember that trip to Paris, Pepe? Remember how much I spoke, how little you spoke? Remember how happy I was, how unhappy you were? Anyway. As I was saying, that I already run out of the alphabet and you have read us so much since those times when you read to discover that books had not taught you to live. I’m leaving. I have an opportunity, not a very definite one it’s true, but an opportunity, in Andorra. An old customer has a hotel there and can’t be bothered to go up and down to keep an eye on how things are going. He’s offered me the job of hotel supervisor. Make sure we don’t get robbed, smile at customers at reception, walk between the tables during dinner and ask the customers if everything is okay. Life there is a bit boring, but very healthy, he tells me, he says he doesn’t know how I can breathe the crap that is breathed in this Chinatown, although they have opened that breach and have been left with their pants down, even more, the neighbourhood’s dirty laundry, handing over a plot as a showcase of so much human ruin. And I’m going to accept. It’s not a bad deal. Meals, board, a hundred thousand a month tax-free, and a consideration that only you have given me, as equals, from one person to another. Biscuter knows Andorra well, from time to time he stole cars there for his weekend sprees and smuggled bottles of whisky and Duralex glassware. Biscuter hasn’t told me yes or no, but you with your silence have told me yes. I would have liked to write to you about nice times; there have been some during our relationship over so many years, but it was an achievement to write what I have written and I take them with me as memories. I don’t want you to feel guilty. Deep down I have always known that you paid attention to me so that you wouldn’t have to pay attention to me and that way you would never feel guilty. I love you. Charo.”

“The arrow passed over the old docks of Barcelona and hit the head of the statue of Columbus, with such bad luck for the admiral that from that moment the eye that looked more eagerly towards America was damaged and, the City Council being broke after the Olympic Games, only a powerful chain of optician’s could act as a sponsor for the repairs. Samaranch was there and it was necessary to reach him with a speed that would not endanger the life of that universal Catalan. The lift had been closed to the public and protected by a strange policewoman dressed like a Catalan folk dancer, surprised once again in the task of making bonfires first, then embers and roasting lamb ribs and pork sausages – the usual union of opposites between the animal of purifying rituals and the impure animal par excellence – that they ate in large quantities, always accompanied by slices of bread with tomato without which the biogenetics of the Catalan people since the nineteenth century could not be explained, when bread with tomato joined the ranks of hallmarks of what it is to be Catalan. Anthropologists call this rite of fire and roasting costellada. It was a matter of sticking the strand on the roast meat, the bread with tomato and the aioli, as an ideal complement to the national-nutrition, which helped Carvalho approach the lift progressively, his interlocutors engrossed in the many facts of national knowledge exhibited by that stranger, until he got into it and set off for its top levels. On his way up, conflicting images, sensations, ideas stirred in an indeterminable place in his brain. Was he going to save Samaranch just for the sake of professionalism? When under the Franco regime hundreds, thousands of anti-fascist activists were arrested – and how they were arrested! – had Samaranch lifted a finger to help them? No doubt the dead guy could provide some information of redemptive generosity, because these people always have the cousin of someone who has helped him cure cataracts or saved from a shooting. The generous fascist has been a constant trope in the History of Spain since the times of Indíbil and Mandonio. In any case, it was Carvalho’s obligation to rescue Samaranch and as soon as he arrived at the terminal station of the statue, Carvalho drew his gun and aimed it precisely against the group of boy scouts that surrounded the recumbent president, tied down by a web of strings tensioned by thick pegs driven into the ground.”

“What do you know about Buenos Aires?”

Neither pessimistic nor optimistic, Carvalho’s voice replied:

“Tango, disappeared, Maradona.”

The old guy nodded more pessimistically still and repeated:

“Tango, disappeared, Maradona.”

Before Carvalho was the view from a Barcelona rooftop, the old man sitting in an armchair, on the horizon the city looked as if it grew as he looked at it. The old man searches for words that seem for him to be hard to find. Behind the curtains of the top floor window two mature women whisper while looking at them sideways. Carvalho remains seated in a wicker armchair à la Emmanuelle, which in the context seems to have been abandoned by an alien rather than a Filipino.

“For the memory of your father, nephew, go to Buenos Aires. I´m looking for my son, for my Raúl.”

He points towards the window where the women are spying.

“I´m in the hands of granddaughters. I don´t want those crows to take what belongs to my son.

Who knows where he might be. I thought he had got over the death of his wife, Berta, the disappearance of his daughter. It was in the tough years of the guerrilla movement. It affected him badly. He was also arrested. I wrote to the King, me, a lifelong Republican. I pleaded for him, me, who had never asked for anything. I agreed to what I would never have agreed to. Finally I brought him to Spain. Time, time heals everything, they say. Time heals nothing. It just adds to its weight. You, you can find him. You know how to do it, aren´t you a policeman?”

“Private detective.”

“It’s the same thing, isn’t it?”

“The police guarantee law and order. I just discover the disorder.”

Carvalho gets up, walks to the railing of the terrace and receives from the city a synthesis of the old and the new Olympic Barcelona, the last warehouses of Pueblo Nuevo, Icaria, the Catalan Manchester, ready for the scrapyard, the rear guard of the eclectic architectures of the Olympic Village and the sea. When his uncle’s voice reaches him like a voice-over, Carvalho smiles slightly.

“Buenos Aires is a beautiful city that is destroying itself.”

His uncle had always told him that the uncle in America spoke very well.

“I like cities that destroy themselves.” Triumphal cities smell of deodorant.

He turns and faces the old man.

“Do you accept? I don’t understand too well what you mean by ‘private detective’ but do you accept?”

“The Magi exist, I know, I know.

His phone call was ‘a religious experience’, I’m still stunned, surprised and babbling (as you will have noticed). I remembered him as being shy, very shy, but apparently arrogant (with me he was arrogant) as well as very busy. That’s why I assumed that, at the most and with luck, he would send me by fax a laconic Yes or No.

I was utterly surprised, not just by the medium, but also by his explanations and even more that I didn’t know what I had to reply to. For the moment, I would only have made him a proposal that, if positive, would translate into a contribution to his palate (some recipes, a wine …, remember?); All this with the aim of compensating for his generous attention to me. I should be fulfilling my undertaking by now, but now I can’t focus on telling him, in detail, the secrets of my “bonito tuna in puff pastry” and my “orange with garlic salad”. You don’t remember me as a cook, on the contrary, but thanks to you I am. You’ve been the man of my life in so many ways! I’d like to send you some bottles of white wine from the Empordá that my family makes, it is fashionable right now to get into the wine business. I’ll need you to tell me if I can send it to your office… Is Biscuter still with you? Do you know that you have a warmer voice than before?, also rhetorical, and a hint of “sufficient” … in Olympus, do all the gods speak like you? Still under the effects of her call yesterday, that is, dazzled, in the clouds, clouds, clouds… (I wish! this could sound as Alberti sounds with his waves, waves, waves…). I’m in a state of grace.

I bought a lovely dress, I am (I feel) really pretty in it, everything yesterday was absolutely perfect.

Laugh all you like, at home there was a family dinner and such was my state of derangement that they decided to set a place on the table for you, so it was more “natural” for me to follow my/our witless, and intimate, conversation; that is: when I looked at his plate no one should interrupt me; I endured jokes of all sorts and I had to tell them about what you had thought about “cold melon soup” and “salt cod a la llauna”…, what envy does!, I told them. It was the dinner menu and you, as usual, though you don’t know it, are present at my dinners, at my lunches, when I do them, when I buy what I need to do them or tell the housekeeper to do them. You are present in what I live and in what I dream and family know it, because Mauricio, my husband, knows that it’s thanks to you we were married and had two splendid children.

There was a funny side to it, more so when I withdrew to rest (they’re on holiday already and extended the after-dinner), with all the stories that are told about you, including the one that affects me. It wasn’t a: ha, ha, ha, no, the general laughter sounded like: haw, haw, haw.

I’m telling you all this because it is only fair that you know the results of your good work yesterday. At this point it won’t be necessary for me to tell you that I’m neither shy nor sensible, and since when asking for something one should not be stingy, on the return from the holidays, as you specified, I will propose an appointment: Boadas, El Viejo Paraguas…, but you choose the place (no, there is no alternative).

Scarlet

(sitting on the stairs and filling a booklet of dances).”

“In fact, the trip would have been totally conventional had we not been victims of sabotage of our car, if Madame Lissieux had not disappeared and instead a load of cocaine turned up in the trunk. Then, in Israel, we help a Russian apprentice biologist skip classes; he disappears and in a hotel we see one of the Armani brothers from the Brindisi-Patras ferry. But we haven’t completely lost the sense of linearity of any round-the-world trip and it’s even possible to do it in eighty days, a daft record of all the daft records that one can achieve. We should travel around the world either in twenty-four hours or in a whole lifetime or several times, according to routes with a single theme. A trip around the world without seeing a ruin, for example, or eating only in McDonald’s or supposing we’re visiting a country that isn’t the one we’re visiting. Imagine, Biscuter, that this isn’t Turkey, but actually Portugal or Argentina, and you will filter everything you see, hear and know through the sieve of your Portuguese or Argentine knowledge. The Bosphorus would be the estuary of the Tagus or the canals of El Tigre of Buenos Aires, and we would be waiting for a German guide to the ruins of Misión or the visit to Fatima. “Is there any other way to alter geography?”

“Geography is what it is.” Biscuter had the gift of stating the obvious, but he added: “When the trip is over we won’t be able to reach similar conclusions, because you started the journey in one place and I started somewhere else, although apparently we left the same port on the same boat. We needn’t coincide in the end.”

“And in the finality?”

“Don’t get too cultured on me.” “What do you understand by finality”

“The what for.” What you’re making the trip for and what I’m making it for.”

Biscuter didn’t reply right away but his eyes lit up indicating that he had understood the question perfectly and that he had an answer that he gave with pleasure, laughing with a hoarse cackle:

“I’m going on the trip to grow, boss, and you are going to say goodbye.”

“I didn’t want to take off my jacket so he wouldn’t see the gun under my armpit. Not because of the gun, nor because of the images of crude violence that it could inspire, but because of the ugliness of the strap that held the holster, like a gloomy invalid’s corset. But I was hot. It’s even likely it was hot. I got up with dissimulated keenness to get closer to the lattice window. On the lawn, the Kennedy family were eating sandwiches. Night was falling. The water in the swimming pool recovered a false tranquillity beneath the grey shadows. A black domestic servant fished for floating dead leaves. Robert Kennedy was doing a handstand and his two eldest children were imitating him. I looked, hesitated, looked again. John Fitzgerald Kennedy was smoking a very long peace pipe from the top of a horse chestnut tree. The shadow of a cloud brought on nightfall. The skin of the bodies grew darker, the skin of the world. Abrupt whiteness was distilled from the Kennedys’ collective teeth. Jacqueline’s voice reached me like a companion I was starting to need.

“Do you think our surveillance system won’t be enough to detect Carvalho?”

“You don’t know the Galicians.”

“Oh, yes I do. I know one or too. A warehouse worker in Detroit and one of Adlai´s cooks. I didn´t notice anything special about them. For the moment they´re not invisible.”

“They´re dangerous and obstinate, like the Jews.”

Jacqueline, with one finger, sealed my lips on hers, while she looked suspiciously at the non-existent corners of the circular room.

“Shut up, please.”

“Queta´s mature flesh fitted better in the framework than the little work of Teresa’s body. What Carvalho could not imagine was the sensations that would pass through the body of a hairdresser from District V in that sanctuary set aside for the repose of an unknown social class. Carvalho remembered how the forties suddenly opened as the miracle of the Plaza de Padró resulting from the crossroads of different streets of District V. He remembered the songs that went up through the inner courtyards to the hum of sewing machines or amid the clatter of the plates hitting the bowls. And he remembered that song sung again and again, mostly by women of the age Queta was now:

“He arrived on a ship with a foreign name and I met him in the harbour at nightfall…”

It was love with a stranger “blond and tall as beer,” “chest tattooed with a heart.” Julio had found in Queta for the first time a psychologically inferior woman who did not give him culture or new experiences, who simply asked him for communication, solidarity, even personal enrichment, something that he could give her, and mystery of youth and distance that in Mr. Ramón were definitely dead and buried.

“We private detectives are the thermometers of established morality, Biscuter. I tell you this society is rotten. It doesn’t believe in anything.”

“Yes, boss.”

Biscuter didn’t tell Carvalho he was right only because he guessed that he was drunk, but because he was already to admit catastrophes.

“Three months and not a sausage. Not one husband looking for his wife. Not one father looking for his daughter. Not one bastard who wants proof that his wife is cheating on him.” “Don’t women run away from home anymore? Or girls?” “Yes, Biscuter. More than ever. But nowadays their husbands and fathers couldn’t care less if they run away. They’ve lost the basic values.” “Didn’t you want democracy?”

“I didn’t mind either way, boss.”

“He saw them on a dune in decline, a few metres from the coming and going of the cold waters of the open Mediterranean, with their backs to the warm waters of the enclosed Mar Menor. She was lying on the sand, wearing a blouse, but without a skirt and the man’s head rested on her lap to be stroked by a female hand to the rhythm of the waves. But from Carvalho’s perspective it was clear that they were not alone. Towards his dune came the corpulent and irremediable body of a man covered with a hat. Carvalho got out of the car, but turned back to it to pull the gun out of the glove compartment, remove the safety catch and wield it before starting a race to the scene that was about to happen. He watched in slow motion as the man in the hat stopped and raised his arms pointing a rifle at the couple and Carvalho shouted Teresa’s name with all his might, a name that became a stone of words that smashed the human balance of the landscape. Teresa arched backwards on herself, Archit jumped to his feet, the man in the hat turned to Carvalho to show him for a moment his “Jungle Kid” face with his eyes furrowed by the decision and then turn back to the couple and point at them. Archit opened his arms and shielded Teresa’s body with his thin boy’s body, to receive a bullet that made him double over, bend forward, and fall limply. Carvalho fired and the bullet lifted dune sand a few metres beyond “Jungle Kid”, who turned and fired at Carvalho and then ran in the direction of a waiting car. Carvalho gave himself the order to wipe his forehead with his hand and then found it full of blood. It didn’t hurt, but he knew he had been hit. He ran towards the Pietá composed of a strident Teresa Marsé who was crying and cursing, cradling Archit’s body on the sand and, when she saw Carvalho arrive, she was slow to recognise him through a barrier of hatred and fear. Carvalho was marked. He knelt down next to Archit, laid him down on the sand, confronted the spectacle of his eyes wandering through the sky in search of a handhold so as not to fall into the pit of death. Carvalho looked up at the sky in the hope of helping Archit find the handhold, the two of them heedless to the woman’s wise heartbreaking sobs. But in the sky there were only flocks of birds scared away by the shots fired by the men and Carvalho believed he had a duty to dispel any doubts Archit might have.

“Swallows. They’re swallows.”

Archit’s lips strove to say something before surrendering to the rigidity of death. Carvalho was convinced that they had tried to repeat the name of the birds, to recognise the birds and, with them, of the great homeland of the skies.”

He didn’t find “Bromuro” in his place of work on the corner of Escudellers Street, nor in the bars and clubs in the area, nor had he left any message in the office. In a bar on Arc del Teatre Street, they hinted at the possibility that he had been taken away in the raid the night before, but “Bromuro” was an individual known to the police and would not be held in a police station more than the strict time of identification. In the boarding house where the shoeshine slept they had not seen him for days, although the owner believed prevention was better than cure and shouted to Carvalho that she was not up to date on the comings and goings of that old, lazy waster who yet again owed her five months’ rent, and one day when he returns he will find the cardboard box on the stairs. From what the landlady then clarified, the cardboard box was the one that had been used to bring the landlady’s colour television and “Bromuro” had asked her to put all his belongings in it.

The lights on the Ramblas were coming on when “Bromuro” knocked on the door of Carvalho’s office and asked for something strong to regain speech and dignity.

“I’ve lost everything in one night, Pepe. I can die now.

Biscuter was more alarmed than Carvalho by the sudden pessimism of the bearded, dirty, dishevelled shoeshine in what remained of the viscous tapestry of his parietals.

“They grabbed me last night, Pepiño, in the raid, a young lieutenant of those they come up with from who knows where and I smiled, this guy will see what will happen the “Bromuro” appear in the police station. And as soon as I arrived I go to the guy on duty and I identify myself. Nothing. As I had told him a petty criminal was there. The guy didn’t even look at me. I demanded that Miraflores or Contreras come out, you know who I’m talking about. He said Miraflores had retired and Contreras didn’t care, he was busy with something else. And me with my balls fuller than Bernarda’s cunt, I roll out my background, my service with the Blue Division and more confident than God himself in the glorious times in which the streets were full of gunmen. So no way, a runt straight out of the police academy and he tells me those merits have expired and he tells me with his little beard and his face of a red [communist] by correspondence course, I can smell those guys a mile off, and me, a real red, a lifelong communist, I respect that, but not some upstart copper and red or democrat to boot, or some unnatural mixture of the above, no way. And he just ignores me there and less and less, man, Pepe, I’m telling you straight up, because I thought to myself, all those bullets, all that going round with no shirt on, stark naked, and then in the end they won’t even accept you as an informer.

…

“It wasn’t scepticism that the manager’s raised eyebrows expressed, with his dark blue Greek sailor’s cap and the grey head of hair supporting the tilt of his head on the saucepan in which Carvalho was putting the finishing touches to his cooking.

“An extra dinner to celebrate what?”

“The impossibility of celebrating anything.” I had felt generous or old and I had offered Charo the option of moving in with me, on a trial basis, for a while, then, who knows. But after thinking about it, not for long, half a minute, she said no, that each person is each person, that she cooks worse than me, that she does her own thing. And with that she left. Also what has happened to me is what happened, me with that idiotic idea of saving the life of a killer who in every way is inadequate and dull. And in those cases there’s nothing like going to the Boqueria to buy stuff you can manipulate and turn into other stuff: vegetables, shellfish, fish, meat. Lately I’ve been thinking about the horror of eating, in relation to the horror of killing. Cooking is an artifice of covering up a savage killing, sometimes perpetrated in conditions of savage, human cruelty, because the supreme adjective of cruelty is ‘human’. Those little birds drowned alive in wine so that they taste better, for example.

“An excellent topic of conversation as an appetiser.

Nineteen eighty-four has only just started. The stars are in alignment and they will shaft us, one after another. It will be a bad year, according to the astrologers. So for that reason and for many others, I went to the Boqueria to get some groceries, ready to cook for myself.

“And for Fuster, for the guinea pig.”

“You’re free to eat it or not.

But above all don’t reject the first course, a meeting between cultures, spinach lightly cooked, drained, chopped and then a gratuitous and absurd artifice, like all culinary artifice. Fry the heads of some prawns in butter. The heads are set aside and with them a light broth is made. Sauté carved garlic, pieces of shrimp and shelled and seasoned clams in the flavoured butter. That dressing is poured over the spinach and let everything cook together, not long, enough for it to aromatise and acquire an unctuous moisture that enters through the eyes. This dressing is poured over the spinach and we leave it all to cook together, not too long, just enough for the aroma to develop and for it to gain a smooth moisture that enters through the eyes. Then we add small kid goat legs, basic, routine, small legs fried till golden in lard, with an onion and cloves, a tomato, mixed herbs. We add the chopped bacon to this base, the liquid from scalded greengages and we make a sauce that evokes the Spanish one, but with a predominant clove aroma, the sugars released by the kid goat legs and the bacon. The scalded plums are arranged on the goat legs, we pour the sauce over that, a brief spell in the oven, and dinner is served. A couple of bottles of Remelluri de Labastida, 78 vintage, and aged with dignity.

“And you get paid for not solving cases?”

“I always solve them. I always get to know almost as much as the murderer and I tell my client everything.

Even in the last case in which my client knew more than I did and always will, he even knows more than the murderer, but it’s as if he didn’t.”

“Biscuter, what would you do to find out the real identity of a dead man, suspecting at the same time that, besides being an assumed name, his face will not be recognised by any sensible Spaniard because he has predictably been living in Mexico for the last forty years?

Biscuter has furrowed his brows concentrating on the question while shaking the shaker.

“Are you asking me, Boss, seriously?

“Yes.”

Well, I would publish a photo of the dead guy in the Mexican press and wait for someone to come forward, a family member or a friend, who recognises the photograph.”

“Biscuter, you have proposed exactly what I have just done. I hope that the Aeromexico pilot I gave the photos to doesn’t go and crash and that they reach their destination.”

“Don’t exaggerate, boss. If the plane crashes, much more would be lost than the photographs. Have you been to Mexico?”

“Yes.”

“Is it such a sick country as they say?”

“It’s a beautiful country.”.

“You could have sent me with the photographs. I never travel, boss. You promised to send me to Paris to do a cookery course, to specialise in soups, and you haven’t sent me.”

“I need to get paid by Nero Wolfe to send you to Paris, Biscuter. But as soon as a murder case comes up and my client is a travel agency, I promise I will ask them to pay you in kind and you will go to Paris. Biscuter, I swear.”

Biscuter is not very convinced. He stops shaking the cocktail shaker, uncorks it and carefully pours a little stream of liquid in a cocktail glass.

“A gimlet, boss, like in the movies.”

Carvalho tastes it.

“You overdid the lime syrup, Biscuter.!

“I’ll add more gin.”

“The gin isn’t right either.” It seems too sweet.

“Today’s not my day.”

Carvalho is paying more attention to the phone than to Biscuter’s self-pity, crestfallen because he never gets any praise, always criticism, always criticism. I made him some baby squid in beer, bloody marvellous, and he still hasn’t told me if he liked them. On the other end of the phone the results are coming in of the people consulted in Carvalho’s search. Sects that existed during the [Spanish] Republic and the Civil War. Finally, an ex-university classmate gives him a lead: Evaristo Tourón, the leading specialist in the conduct of sects during the war. He won’t come to the phone: he’s a real wise man. Real wise men never answer the telephone. Can you imagine Einstein on the phone? Evaristo Tourón has his ivory tower in a villa in the scenic location of Permanyer, an island in the rectangular and grey chessboard of the Ensanche district of Barcelona, fifty metres away from the traffic jams, in a microclimate of silence and subdued palm trees.”

“Sometimes they pay me without fucking and then they don’t leave me a tip. Signs, Pepe, signs that this is coming to an end and I will be fifty with more makeup than ever, with more creams than ever, waiting next to the telephone for someone to call me and you don’t call me. It wouldn’t have been better if I had told you in person what I’m going to tell you. I see it very clearly. Better to put it in writing and you remember me as I was, as we were the last afternoon you took me for a walk to get my nerve out or on that trip to Paris that, finally, we made last spring. Remember that trip to Paris, Pepe? Remember how much I spoke, how little you spoke? Remember how happy I was, how unhappy you were? Anyway. As I was saying, that I already run out of the alphabet and you have read us so much since those times when you read to discover that books had not taught you to live. I’m leaving. I have an opportunity, not a very definite one it’s true, but an opportunity, in Andorra. An old customer has a hotel there and can’t be bothered to go up and down to keep an eye on how things are going. He’s offered me the job of hotel supervisor. Make sure we don’t get robbed, smile at customers at reception, walk between the tables during dinner and ask the customers if everything is okay. Life there is a bit boring, but very healthy, he tells me, he says he doesn’t know how I can breathe the crap that is breathed in this Chinatown, although they have opened that breach and have been left with their pants down, even more, the neighbourhood’s dirty laundry, handing over a plot as a showcase of so much human ruin. And I’m going to accept. It’s not a bad deal. Meals, board, a hundred thousand a month tax-free, and a consideration that only you have given me, as equals, from one person to another. Biscuter knows Andorra well, from time to time he stole cars there for his weekend sprees and smuggled bottles of whisky and Duralex glassware. Biscuter hasn’t told me yes or no, but you with your silence have told me yes. I would have liked to write to you about nice times; there have been some during our relationship over so many years, but it was an achievement to write what I have written and I take them with me as memories. I don’t want you to feel guilty. Deep down I have always known that you paid attention to me so that you wouldn’t have to pay attention to me and that way you would never feel guilty. I love you. Charo.”

“The arrow passed over the old docks of Barcelona and hit the head of the statue of Columbus, with such bad luck for the admiral that from that moment the eye that looked more eagerly towards America was damaged and, the City Council being broke after the Olympic Games, only a powerful chain of optician’s could act as a sponsor for the repairs. Samaranch was there and it was necessary to reach him with a speed that would not endanger the life of that universal Catalan. The lift had been closed to the public and protected by a strange policewoman dressed like a Catalan folk dancer, surprised once again in the task of making bonfires first, then embers and roasting lamb ribs and pork sausages – the usual union of opposites between the animal of purifying rituals and the impure animal par excellence – that they ate in large quantities, always accompanied by slices of bread with tomato without which the biogenetics of the Catalan people since the nineteenth century could not be explained, when bread with tomato joined the ranks of hallmarks of what it is to be Catalan. Anthropologists call this rite of fire and roasting costellada. It was a matter of sticking the strand on the roast meat, the bread with tomato and the aioli, as an ideal complement to the national-nutrition, which helped Carvalho approach the lift progressively, his interlocutors engrossed in the many facts of national knowledge exhibited by that stranger, until he got into it and set off for its top levels. On his way up, conflicting images, sensations, ideas stirred in an indeterminable place in his brain. Was he going to save Samaranch just for the sake of professionalism? When under the Franco regime hundreds, thousands of anti-fascist activists were arrested – and how they were arrested! – had Samaranch lifted a finger to help them? No doubt the dead guy could provide some information of redemptive generosity, because these people always have the cousin of someone who has helped him cure cataracts or saved from a shooting. The generous fascist has been a constant trope in the History of Spain since the times of Indíbil and Mandonio. In any case, it was Carvalho’s obligation to rescue Samaranch and as soon as he arrived at the terminal station of the statue, Carvalho drew his gun and aimed it precisely against the group of boy scouts that surrounded the recumbent president, tied down by a web of strings tensioned by thick pegs driven into the ground.”

“What do you know about Buenos Aires?”

Neither pessimistic nor optimistic, Carvalho’s voice replied:

“Tango, disappeared, Maradona.”

The old guy nodded more pessimistically still and repeated:

“Tango, disappeared, Maradona.”

Before Carvalho was the view from a Barcelona rooftop, the old man sitting in an armchair, on the horizon the city looked as if it grew as he looked at it. The old man searches for words that seem for him to be hard to find. Behind the curtains of the top floor window two mature women whisper while looking at them sideways. Carvalho remains seated in a wicker armchair à la Emmanuelle, which in the context seems to have been abandoned by an alien rather than a Filipino.

“For the memory of your father, nephew, go to Buenos Aires. I´m looking for my son, for my Raúl.”

He points towards the window where the women are spying.

“I´m in the hands of granddaughters. I don´t want those crows to take what belongs to my son.

Who knows where he might be. I thought he had got over the death of his wife, Berta, the disappearance of his daughter. It was in the tough years of the guerrilla movement. It affected him badly. He was also arrested. I wrote to the King, me, a lifelong Republican. I pleaded for him, me, who had never asked for anything. I agreed to what I would never have agreed to. Finally I brought him to Spain. Time, time heals everything, they say. Time heals nothing. It just adds to its weight. You, you can find him. You know how to do it, aren´t you a policeman?”

“Private detective.”

“It’s the same thing, isn’t it?”

“The police guarantee law and order. I just discover the disorder.”

Carvalho gets up, walks to the railing of the terrace and receives from the city a synthesis of the old and the new Olympic Barcelona, the last warehouses of Pueblo Nuevo, Icaria, the Catalan Manchester, ready for the scrapyard, the rear guard of the eclectic architectures of the Olympic Village and the sea. When his uncle’s voice reaches him like a voice-over, Carvalho smiles slightly.

“Buenos Aires is a beautiful city that is destroying itself.”

His uncle had always told him that the uncle in America spoke very well.

“I like cities that destroy themselves.” Triumphal cities smell of deodorant.

He turns and faces the old man.

“Do you accept? I don’t understand too well what you mean by ‘private detective’ but do you accept?”

“The Magi exist, I know, I know.

His phone call was ‘a religious experience’, I’m still stunned, surprised and babbling (as you will have noticed). I remembered him as being shy, very shy, but apparently arrogant (with me he was arrogant) as well as very busy. That’s why I assumed that, at the most and with luck, he would send me by fax a laconic Yes or No.

I was utterly surprised, not just by the medium, but also by his explanations and even more that I didn’t know what I had to reply to. For the moment, I would only have made him a proposal that, if positive, would translate into a contribution to his palate (some recipes, a wine …, remember?); All this with the aim of compensating for his generous attention to me. I should be fulfilling my undertaking by now, but now I can’t focus on telling him, in detail, the secrets of my “bonito tuna in puff pastry” and my “orange with garlic salad”. You don’t remember me as a cook, on the contrary, but thanks to you I am. You’ve been the man of my life in so many ways! I’d like to send you some bottles of white wine from the Empordá that my family makes, it is fashionable right now to get into the wine business. I’ll need you to tell me if I can send it to your office… Is Biscuter still with you? Do you know that you have a warmer voice than before?, also rhetorical, and a hint of “sufficient” … in Olympus, do all the gods speak like you? Still under the effects of her call yesterday, that is, dazzled, in the clouds, clouds, clouds… (I wish! this could sound as Alberti sounds with his waves, waves, waves…). I’m in a state of grace.

I bought a lovely dress, I am (I feel) really pretty in it, everything yesterday was absolutely perfect.

Laugh all you like, at home there was a family dinner and such was my state of derangement that they decided to set a place on the table for you, so it was more “natural” for me to follow my/our witless, and intimate, conversation; that is: when I looked at his plate no one should interrupt me; I endured jokes of all sorts and I had to tell them about what you had thought about “cold melon soup” and “salt cod a la llauna”…, what envy does!, I told them. It was the dinner menu and you, as usual, though you don’t know it, are present at my dinners, at my lunches, when I do them, when I buy what I need to do them or tell the housekeeper to do them. You are present in what I live and in what I dream and family know it, because Mauricio, my husband, knows that it’s thanks to you we were married and had two splendid children.

There was a funny side to it, more so when I withdrew to rest (they’re on holiday already and extended the after-dinner), with all the stories that are told about you, including the one that affects me. It wasn’t a: ha, ha, ha, no, the general laughter sounded like: haw, haw, haw.

I’m telling you all this because it is only fair that you know the results of your good work yesterday. At this point it won’t be necessary for me to tell you that I’m neither shy nor sensible, and since when asking for something one should not be stingy, on the return from the holidays, as you specified, I will propose an appointment: Boadas, El Viejo Paraguas…, but you choose the place (no, there is no alternative).

Scarlet

(sitting on the stairs and filling a booklet of dances).”

“In fact, the trip would have been totally conventional had we not been victims of sabotage of our car, if Madame Lissieux had not disappeared and instead a load of cocaine turned up in the trunk. Then, in Israel, we help a Russian apprentice biologist skip classes; he disappears and in a hotel we see one of the Armani brothers from the Brindisi-Patras ferry. But we haven’t completely lost the sense of linearity of any round-the-world trip and it’s even possible to do it in eighty days, a daft record of all the daft records that one can achieve. We should travel around the world either in twenty-four hours or in a whole lifetime or several times, according to routes with a single theme. A trip around the world without seeing a ruin, for example, or eating only in McDonald’s or supposing we’re visiting a country that isn’t the one we’re visiting. Imagine, Biscuter, that this isn’t Turkey, but actually Portugal or Argentina, and you will filter everything you see, hear and know through the sieve of your Portuguese or Argentine knowledge. The Bosphorus would be the estuary of the Tagus or the canals of El Tigre of Buenos Aires, and we would be waiting for a German guide to the ruins of Misión or the visit to Fatima. “Is there any other way to alter geography?”

“Geography is what it is.” Biscuter had the gift of stating the obvious, but he added: “When the trip is over we won’t be able to reach similar conclusions, because you started the journey in one place and I started somewhere else, although apparently we left the same port on the same boat. We needn’t coincide in the end.”

“And in the finality?”

“Don’t get too cultured on me.” “What do you understand by finality”

“The what for.” What you’re making the trip for and what I’m making it for.”

Biscuter didn’t reply right away but his eyes lit up indicating that he had understood the question perfectly and that he had an answer that he gave with pleasure, laughing with a hoarse cackle:

“I’m going on the trip to grow, boss, and you are going to say goodbye.”

Adaptations

Series and films

Tatuaje. Dir. Bigas Luna, 1976, Luna Films

Asesinato en el Comité Central. Dir. Vicente Aranda, 1982. Presentation and trailer at RTVE play.

Olímpicament mort. Dir. Manuel Esteban, 1985, TV3.

El laberinto griego. Dir. Rafael Alcázar, 1992, Impala Trabala Producciones.

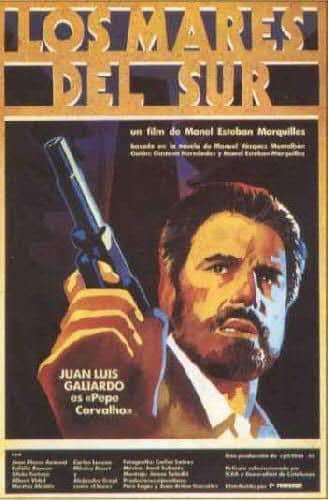

Los mares del Sur. Dir. Manuel Esteban, 1992, Cyrk, Institut del Cinema Català.

Pepe Carvalho en Buenos Aires. Dir. Luis Baroné.

Comic

Other thriller novels